Difference between revisions of "Waltharius13"

| (15 intermediate revisions by 5 users not shown) | |||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

| + | ===The Franks under Gibich surrender to Attila, giving Hagen as a hostage (13–33)=== | ||

{| | {| | ||

|- | |- | ||

| Line 6: | Line 7: | ||

}} | }} | ||

| | | | ||

| − | | | + | |{{Pictures|[[Image:Europe500.png|center|thumb]]}} |

|{{Meter|scansion=DDSSDS}} | |{{Meter|scansion=DDSSDS}} | ||

| − | | | + | |{{Comment|After briefly introducing the reader to the general stage of the poem and to the specific character (Attila) who precipitates its drama, the poet takes the narrative quickly to action. Note the opening dactyls that spring the reader right into Attila's breaking camp. <br />The Franks are the first of three peoples introduced from which the four major characters come. Just as the later sequential battle scenes of lines 640-1061 are somewhat repetitive, lines 13-92 present in similar terms the reactions of the Franks, Burgundians and Aquitanians to the threat of invading Huns: all of them offer a treaty and supply a hostage.}} |

|- | |- | ||

|[[Quorum]] [[rex]] [[Gibicho]] [[solio]] [[pollebat]] [[in]] [[alto]], | |[[Quorum]] [[rex]] [[Gibicho]] [[solio]] [[pollebat]] [[in]] [[alto]], | ||

| Line 28: | Line 29: | ||

| | | | ||

|{{Meter|scansion=DSSSDS}} | |{{Meter|scansion=DSSSDS}} | ||

| − | | | + | |{{Comment| As Gunther is introduced to the reader first in line 15 but only in line 16 by name, so the parenthetical "quam postea narro" that indicates Gunther functions as the type of literary device (akin to foreshadowing) that is known as "Chekhov's gun." The syntactical delay between the introduction of Gunther and his name mirrors the narrative delay between his introduction and the part he plays in the poem, which begins at line 441.}} |

|- | |- | ||

|[[Namque]] [[marem]] [[genuit]], [[quem1|quem]] [[Guntharium]] [[vocitavit]]. | |[[Namque]] [[marem]] [[genuit]], [[quem1|quem]] [[Guntharium]] [[vocitavit]]. | ||

| Line 46: | Line 47: | ||

| | | | ||

|{{Meter|scansion=DDSSDS}} | |{{Meter|scansion=DDSSDS}} | ||

| − | | | + | |{{Comment|"Fama volans": In many epics "Fama" acts as herald of armies or war. The epithet "volans" give the rumor an urgency and desperation that often influences the decisions made, as happens here. "Fama" is even accompanied by "volans" in one form or another several times in the Aeneid, 11.139-40, 3.121-22, and 8.554-55. Cf. line 170 in which "Fama" announces the rebellion of a certain recently conquered tribe; absent the "volans", that scene lacks the immediacy that this one has. |

| + | |||

| + | '''It appears to me that Fama is personified as a flying being because rumors travel so very quickly. [JJTY]'''}} | ||

|- | |- | ||

|[[Dicens]] [[hostilem]] [[cuneum]] [[transire]] [[per]] [[Hystrum]], | |[[Dicens]] [[hostilem]] [[cuneum]] [[transire]] [[per]] [[Hystrum]], | ||

| Line 53: | Line 56: | ||

}} | }} | ||

| | | | ||

| − | | | + | |{{Pictures|[[Image:Europe500.png|center|thumb|Danube River]]}} |

|{{Meter|scansion=SSDSDS}} | |{{Meter|scansion=SSDSDS}} | ||

| − | | | + | |{{Comment| "Hister": the Latin name for the Danube River, from the Greek ᾽´Ιστρος. Both words referred particularly to the lower Danube and the area around its mouth on the Black Sea. The assertion that the passage of the Huns across the Danube inspired fear in a Frankish king does not make geographical sense, but perhaps it is a case of metonymy for unknown regions even further to the east.}} |

|- | |- | ||

|[[Vincentem]] [[numero]] [[stellas]] [[atque]] [[amnis]] [[arenas]]. | |[[Vincentem]] [[numero]] [[stellas]] [[atque]] [[amnis]] [[arenas]]. | ||

| Line 71: | Line 74: | ||

|{{Commentary|''Qui'': Gibicho | |{{Commentary|''Qui'': Gibicho | ||

}} | }} | ||

| − | |{{Parallel|'' | + | |{{Parallel|''Aeneid'' 3.51-52.: . . .''cum iam diffideret armis/ Dardaniae cingique urbem obsidione videret''. ‘. . .When he now lost hope in the arms of Dardania and saw the city beleagured.’ 8.518: ''robora pubis''. . . ‘The choice flower of manhood. . .’ |

}} | }} | ||

| | | | ||

|{{Meter|scansion=SSSSDS}} | |{{Meter|scansion=SSSSDS}} | ||

| − | | | + | |{{Comment|The heavily spondaic nature of the line - SSSSDS - could reflect the Gibicho's dread and loss of confidence.}} |

|- | |- | ||

|[[Concilium]] [[cogit]], [[quae3|quae]] [[sint]] [[facienda]], [[requirit]]. | |[[Concilium]] [[cogit]], [[quae3|quae]] [[sint]] [[facienda]], [[requirit]]. | ||

| | | | ||

| | | | ||

| − | |{{Parallel|'' | + | |{{Parallel|''Aeneid'' 11.234-235.: ''ergo concilium magnum primosque suorum/ imperio accitos alta intra limina cogit''. ‘Therefore his high council, the foremost of his people, he summons by royal command and convenes within his lofty portals.’ 11.303-304.: ''fuerat melius, non tempore tali/ cogere concilium. '' ‘It would have been better not to convene a council at such an hour.’ |

}} | }} | ||

| | | | ||

| Line 99: | Line 102: | ||

|{{Commentary|''Darent'': sc. ''Huni'' | |{{Commentary|''Darent'': sc. ''Huni'' | ||

}} | }} | ||

| − | |{{Parallel|'' | + | |{{Parallel|''Aeneid'' 1.408-409.: ''cur dextrae iungere dextram/ non datur. . .?'' ‘Why am I not allowed to clasp hand in hand? 8.163-164: ''mihi mens iuvenali ardebat amore/ compellare virum et dextrae coniungere dextram. '' ‘My heart burned with youthful ardour to speak to him and clasp hand in hand.’ |

}} | }} | ||

| | | | ||

| Line 146: | Line 149: | ||

|{{Parallel|''Verba Dierum seu Paralipomenon I'' 12.28: ''Sadoc etiam puer egregiae indolis''. ‘Sadoc also was a young man of excellent disposition.’ ''Aeneid'' 5.373: ''Bebrycia veniens Amyci de gente''. . . ‘Offspring of Amycus’ Bebrycian race. . .’ | |{{Parallel|''Verba Dierum seu Paralipomenon I'' 12.28: ''Sadoc etiam puer egregiae indolis''. ‘Sadoc also was a young man of excellent disposition.’ ''Aeneid'' 5.373: ''Bebrycia veniens Amyci de gente''. . . ‘Offspring of Amycus’ Bebrycian race. . .’ | ||

}} | }} | ||

| − | | | + | |{{Pictures|[[Image:Europe500.png|center|thumb]]}} |

|{{Meter|scansion=DDDSDS}} | |{{Meter|scansion=DDDSDS}} | ||

| − | | | + | |{{Comment|[Similar to the note to the left.] The Franks were forerunners of the Merovingians, who were said to be descended from Trojan stock. Hagan is not the only Frank said to descend from such ancient lineage, since in 725-729 Gunther's warrior Werinhard is described as being a descendant of the Trojan Pandarus.}} |

|- | |- | ||

|[[hunc2|Hunc]], [[quia]] [[Guntharius]] [[nondum]] [[pervenit1|pervenit]] [[ad]] [[aevum1|aevum]], | |[[hunc2|Hunc]], [[quia]] [[Guntharius]] [[nondum]] [[pervenit1|pervenit]] [[ad]] [[aevum1|aevum]], | ||

| Line 184: | Line 187: | ||

| | | | ||

|- | |- | ||

| − | |[[Deveniunt]] | + | |[[Deveniunt]] [[pacemque]] [[rogant]] [[ac]] [[foedera]] [[firmant]]. |

| | | | ||

| | | | ||

Latest revision as of 05:15, 16 December 2009

The Franks under Gibich surrender to Attila, giving Hagen as a hostage (13–33)

| Qui sua castra movens mandavit visere Francos, | Francos: Germanic peoples who settled along the Rhine during the late Roman Empire, forerunners of the Merovingians and Carolingians.

|

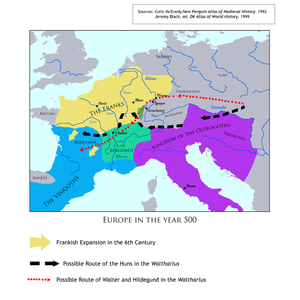

DDSSDS | After briefly introducing the reader to the general stage of the poem and to the specific character (Attila) who precipitates its drama, the poet takes the narrative quickly to action. Note the opening dactyls that spring the reader right into Attila's breaking camp. The Franks are the first of three peoples introduced from which the four major characters come. Just as the later sequential battle scenes of lines 640-1061 are somewhat repetitive, lines 13-92 present in similar terms the reactions of the Franks, Burgundians and Aquitanians to the threat of invading Huns: all of them offer a treaty and supply a hostage. | |||

| Quorum rex Gibicho solio pollebat in alto, | Gibicho: The name Gibica is attested for a King of Burgundy, possibly mythical, in the Lex Burgundionum (iii) of 501 A.D. Perhaps because the Burgundians were conquered by the Franks in 534, the poet makes Gibicho and his son Franks, while giving the Burgundians their own independent existence below (cf. line 34 ff.).

|

Aeneid 8.541: solio se tollit ab alto. ‘He rose from his lofty throne.’ 11.301: solio rex infit ab alto. ‘The king, first calling on heaven, from his high throne begins.’ Prudentius, Psychomachia 875: hoc residet solio pollens Sapientia. ‘Here mighty Wisdom sits enthroned.’

|

SDDSDS | |||

| Prole recens orta gaudens, quam postea narro: | 15 | Quam postea narro: i.e., the proles, Guntharius or Gunther, who enters the narrative as a major character at line 441.

|

Georgics 3.156: sole recens orto. . . ‘When the sun is new-risen. . .’ Prudentius, Psychomachia Praefatio 49: herede gaudens. . . ‘Rejoicing in an heir. . .’

|

DSSSDS | As Gunther is introduced to the reader first in line 15 but only in line 16 by name, so the parenthetical "quam postea narro" that indicates Gunther functions as the type of literary device (akin to foreshadowing) that is known as "Chekhov's gun." The syntactical delay between the introduction of Gunther and his name mirrors the narrative delay between his introduction and the part he plays in the poem, which begins at line 441. | |

| Namque marem genuit, quem Guntharium vocitavit. | Guntharium: Another name attested for a King of Burgundy in the Lex Burgundionum. Also the name of a central figure in the Nibelungenlied.

|

DDSDDS | ||||

| Fama volans pavidi regis transverberat aures, | Aeneid 11.139-140.: et iam Fama volans, tanti praenuntia luctus,/ Evandrum Evandrique domos et moenia replet. ‘And now Rumour in her flight, heralding this piercing woe, fills Evander’s ears, his palace and his city.’ 3.121-122.: Fama volat pulsum regnis cessisse paternis/ Idomenea ducem, desertaque litora Cretae. ‘A rumour flies that Idomeneus, the chieftain, has left his father’s realm for exile, that the shores of Crete are abandoned.’ 8.554-555.: Fama volat parvam subito vulgata per urbem/ ocius ire equites Tyrrheni ad litora regis. ‘Suddenly, spreading through the little town, flies a rumour that horsemen are speeding to the shores of the Tyrrhene king.’ 9.473-474.: Interea pavidam volitans pennata per urbem/ nuntia Fama ruit. ‘Meanwhile, winged Fame, flitting through the fearful town, speeds with the news.’

|

DDSSDS | "Fama volans": In many epics "Fama" acts as herald of armies or war. The epithet "volans" give the rumor an urgency and desperation that often influences the decisions made, as happens here. "Fama" is even accompanied by "volans" in one form or another several times in the Aeneid, 11.139-40, 3.121-22, and 8.554-55. Cf. line 170 in which "Fama" announces the rebellion of a certain recently conquered tribe; absent the "volans", that scene lacks the immediacy that this one has.

It appears to me that Fama is personified as a flying being because rumors travel so very quickly. [JJTY] | |||

| Dicens hostilem cuneum transire per Hystrum, | Cuneum: a wedge-shaped column of troops, a formation used by Germanic tribes according to Tac. Germ. 6. Hystrum: the Danube River.

|

SSDSDS | "Hister": the Latin name for the Danube River, from the Greek ᾽´Ιστρος. Both words referred particularly to the lower Danube and the area around its mouth on the Black Sea. The assertion that the passage of the Huns across the Danube inspired fear in a Frankish king does not make geographical sense, but perhaps it is a case of metonymy for unknown regions even further to the east. | |||

| Vincentem numero stellas atque amnis arenas. | Amnis equiv. tomaris

|

Liber Genesis 22.17: benedicam tibi et multiplicabo semen tuum sicut stellas caeli et velut harenam quae est in litore maris. ‘I will bless thee, and I will multiply thy seed as the stars of heaven, and as the sand that is by the sea shore.’

|

SDSSDS Elision: atque amnis |

|||

| Qui non confidens armis vel robore plebis | 20 | Qui: Gibicho

|

Aeneid 3.51-52.: . . .cum iam diffideret armis/ Dardaniae cingique urbem obsidione videret. ‘. . .When he now lost hope in the arms of Dardania and saw the city beleagured.’ 8.518: robora pubis. . . ‘The choice flower of manhood. . .’

|

SSSSDS | The heavily spondaic nature of the line - SSSSDS - could reflect the Gibicho's dread and loss of confidence. | |

| Concilium cogit, quae sint facienda, requirit. | Aeneid 11.234-235.: ergo concilium magnum primosque suorum/ imperio accitos alta intra limina cogit. ‘Therefore his high council, the foremost of his people, he summons by royal command and convenes within his lofty portals.’ 11.303-304.: fuerat melius, non tempore tali/ cogere concilium. ‘It would have been better not to convene a council at such an hour.’

|

DSSDDS | ||||

| Consensere omnes foedus debere precari | Aeneid 2.130: adsensere omnes. ‘All approved.’ 12.242-243.: nunc arma volunt foedusque precantur/ infectum. ‘Now they long for arms, and pray that the covenant be undone.’

|

SSSSDS Elision: consensere omnes |

||||

| Et dextras, si forte darent, coniungere dextris | Darent: sc. Huni

|

Aeneid 1.408-409.: cur dextrae iungere dextram/ non datur. . .? ‘Why am I not allowed to clasp hand in hand? 8.163-164: mihi mens iuvenali ardebat amore/ compellare virum et dextrae coniungere dextram. ‘My heart burned with youthful ardour to speak to him and clasp hand in hand.’

|

SSDSDS | |||

| Obsidibusque datis censum persolvere iussum; | Censum: “tribute”

|

DDSSDS | ||||

| Hoc melius fore quam vitam simul ac regionem | 25 | DDSDDS | ||||

| Perdiderint natosque suos pariterque maritas. | Perdiderint: perfect subjunctive parallel to the infinitive fore.

|

DSDDDS | ||||

| Nobilis hoc Hagano fuerat sub tempore tiro | Hagano: Probably legendary; in the Nibelungenlied the brother of Gunther. Tiro equiv. toiuvenis

|

DDDSDS | ||||

| Indolis egregiae, veniens de germine Troiae. | De germine Troiae: Troja was the Roman name for present-day Kirchheim in Alsace, possibly Hagen’s original hometown. A story first found in the Chronicle of Fredegar, however, connected the Franks, like the Romans, with the Trojans, and the poet may be alluding here to that legendary tradition, as he does more directly in lines 726-729. Egregiae…Troiae: an example of internal “Leonine” rhyme.

|

Verba Dierum seu Paralipomenon I 12.28: Sadoc etiam puer egregiae indolis. ‘Sadoc also was a young man of excellent disposition.’ Aeneid 5.373: Bebrycia veniens Amyci de gente. . . ‘Offspring of Amycus’ Bebrycian race. . .’

|

DDDSDS | [Similar to the note to the left.] The Franks were forerunners of the Merovingians, who were said to be descended from Trojan stock. Hagan is not the only Frank said to descend from such ancient lineage, since in 725-729 Gunther's warrior Werinhard is described as being a descendant of the Trojan Pandarus. | ||

| Hunc, quia Guntharius nondum pervenit ad aevum, | DDSSDS | |||||

| Ut sine matre queat vitam retinere tenellam, | 30 | DDSDDS | ||||

| Cum gaza ingenti decernunt mittere regi. | Aeneid 7.152-153.: tum satus Anchisa delectos ordine ab omni/ centum oratores augusta ad moenia regis/ ire iubet. . .donaque ferre viro pacemque exposcere Teucris./ haud mora, festinant. ‘Then Anchises’ son commands a hundred envoys, chosen from every rank, to go to the king’s stately city to bear gifts to the hero and crave peace for the Trojans. They linger not, but hasten.’

|

SSSSDS Elision: gaza ingenti |

||||

| Nec mora, legati censum iuvenemque ferentes | Aeneid 7.152-153.: tum satus Anchisa delectos ordine ab omni/ centum oratores augusta ad moenia regis/ ire iubet. . .donaque ferre viro pacemque exposcere Teucris./ haud mora, festinant. ‘Then Anchises’ son commands a hundred envoys, chosen from every rank, to go to the king’s stately city to bear gifts to the hero and crave peace for the Trojans. They linger not, but hasten.’

|

DSSDDS | ||||

| Deveniunt pacemque rogant ac foedera firmant. | Statius, Thebaid 12.509: conveniunt pacemque rogant. ‘They gather and seek for peace.’ Aeineid 11.330: qui dicta ferent et foedera firment. ‘Those who may bring the news and seal the pact. . .’

|

DSDSDS |

| « previous |

|

next » | English |