Waltharius34

The Burgundians under Hereric surrender to Attila, giving Hildegund as a hostage (34–74)

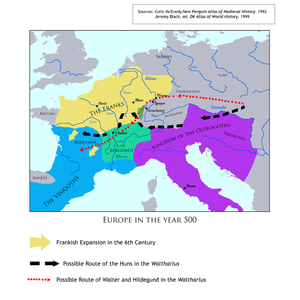

| Tempore quo validis steterat Burgundia sceptris, | Tempore quo equiv. to eo tempore Steterat: The poet, perhaps due to his German origins, makes very free use of the tenses of the Latin verb. Pluperfect forms in particular are often used as a simple past tense. Burgundia: A Germanic kingdom conquered by the Huns in 437 A.D. (as related in both the Waltharius and the Nibelungenlied), after which its people reestablished themselves in the south-eastern quadrant of present-day France, before being conquered by the Franks in the following century.

|

Aeneid 9.80: tempore quo. . . ‘In the days when. . .’

|

DDDSDS | "sceptris": metonymy for king or ruler. | ||

| Cuius primatum Heriricus forte gerebat. | 35 | Primatum equiv. to imperium Heriricus: Probably legendary; Althof considers this name to have been invented by the poet. Forte: an adverb often used in the Waltharius, like fors, simply metri causa.

|

Epistula Iohannis III 9: sed is qui amat primatum gerere. . . ‘He who loveth to have the pre-eminence among them. . .’ Aeineid 12.206: dextra sceptrum nam forte gerebat. ‘For by chance in his hand he held his sceptre.’

|

SSDSDS Hiatus: primatum Heriricus |

||

| Filia huic tantum fuit unica nomine Hiltgunt, | Hiltgunt: The princess, who also figures in the Nibelungenlied, is not known to have been historical. The Burgundians, unlike the Franks, did not use the Salic Law that barred women from inheriting the throne.

|

Secundum Lucam 8.42: quia filia unica erat illi. ‘For he had an only daughter.’

|

DSDDDS Hiatus: nomine Hiltgunt |

|||

| Nobilitate quidem pollens ac stemmate formae. | Ovid, Matamorphoses 13.22: nobilitate potens essem. ‘I should still be his superior in birth.’ Prudentius, Peristephanon Liber 1.4: pollet hoc felix per orbem terra Hibera stemmate. ‘For this glory the land of Spain has the fortune to be held in honour through all the world.’

|

DDSSDS | ||||

| Debuit haec heres aula residere paterna | DSSDDS | |||||

| Atque diu congesta frui, si forte liceret. | Diu congesta frui: an accusative follows fruor here instead of the usual ablative.

|

DSDSDS | ||||

| Namque Avares firma cum Francis pace peracta | 40 | Avares: This name is used interchangeably by the poet with Huni for Attila’s Huns. In fact, the Avars were another separate group that invaded Europe from the east around 560 A.D., eventually settling in the Pannonian region.

|

DSSDDS Elision: namque Avares |

"Avares": the use of the term Avars for Huns could offer further evidence of the poet's misconceptions about both the identity of the Huns and the length of their reign, but he could very well be taking advantage of the poetic license in epic (especially Virgilian epic) to use different names for the same people. | ||

| Suspendunt a fine quidem regionis eorum. | Suspendunt: “held back”

|

SSDDDS | ||||

| Attila sed celeres mox huc deflectit habenas, | Aeneid 11.765: hac iuvenis furtim celeris detorquet habenas. ‘There the youth stealthily turns his swift reins.’ 12.471: undantis flectit habenas. ‘She guides the flowing thongs.’

|

DDSSDS | ||||

| Nec tardant reliqui satrapae vestigia adire. | Satrapae: “leader, king.” A Persian word that came to Latin through Greek. In Classical authors it is a third-declension noun in the singular, but the poet of the Waltharius makes it a masculine first-declension noun like nauta. Pace Wieland, it seems likely that here we have the genitive singular referring to Attila (cf. lines 170, 371, 573, 1126), rather than the nominative plural, referring to his immediate vassals, as in lines 136, 278.

|

|

SDDSDS Elision: vestigia adire |

|||

| Ibant aequati numero, sed et agmine longo, | Sed et: The use of two conjunctions is metri causa, as frequently in the poem.

|

Aeneid 7.698: ibant aequati numero regemque canebant. ‘In dressed lines they marched and sang their king.’ 10.769: in agmine longo. . . ‘In a long battle line. . .’ 8.595-596.: agmine facto/ quadripedante putrem sonitu quatit ungula campum. ‘They form in column, and with galloping tread the horse hoof shakes the crumbling plain.’ 11.875: quadripedumque putrem cursu quatit ungula campum. ‘In their galloping course the horsehoof shakes the crumbling plain.’ 7.722: scuta sonant pulsuque pedum conterrita tellus. ‘The bucklers clang, and the earth trembles under the tramping feet.’ 9.709: dat tellus gemitum et clipeum super intonat ingens. ‘The earth groans, and the huge shield thunders over him.’ 8.239: intonat aether. . . ‘Heaven thunders. . .’

|

SSDDDS | |||

| Quadrupedum cursu tellus concussa gemebat. | 45 | Aeneid 7.698: ibant aequati numero regemque canebant. ‘In dressed lines they marched and sang their king.’ 10.769: in agmine longo. . . ‘In a long battle line. . .’ 8.595-596.: agmine facto/ quadripedante putrem sonitu quatit ungula campum. ‘They form in column, and with galloping tread the horse hoof shakes the crumbling plain.’ 11.875: quadripedumque putrem cursu quatit ungula campum. ‘In their galloping course the horsehoof shakes the crumbling plain.’ 7.722: scuta sonant pulsuque pedum conterrita tellus. ‘The bucklers clang, and the earth trembles under the tramping feet.’ 9.709: dat tellus gemitum et clipeum super intonat ingens. ‘The earth groans, and the huge shield thunders over him.’ 8.239: intonat aether. . . ‘Heaven thunders. . .’

|

DSSSDS | |||

| Scutorum sonitu pavidus superintonat aether. | SDDDDS | |||||

| Ferrea silva micat totos rutilando per agros: | Rutilando: This use of the ablative of the gerund foreshadows the form’s transformation into the present participle of some modern Romance languages.

|

Statius, Thebaid 4.220-221.: ferrea curru/ silva tremit. ‘An iron forest trembles on his chariot.’ Aeneid 11.601-602.: tum late ferreus hastis/ horret ager campique armis sublimibus ardent. ‘Far and wide the field bristles with the steel of spears, and the plains are ablaze with raised weapons.’ 3.45-46.: hic confixum ferrea texit/ telorum seges. ‘Here an iron harvest of spears covered my pierced body.’

|

DDSDDS | |||

| Haud aliter primo quam pulsans aequora mane | Aeneid 1.399: haud aliter. . . ‘Likewise. . .’

|

DSSSDS | ||||

| Pulcher in extremis renitet sol partibus orbis. | Ovid, Tristia ex Ponto 3.3.3: aeger in extremis ignoti partibus orbis. ‘Ill in the utmost part of an unknown world.’

|

DSDSDS | ||||

| Iamque Ararim Rodanumque amnes transiverat altos | 50 | Ararim: The Saône River. Rodanum: The Rhône River (a geographic error, since this river does not need to be crossed coming from Worms, the seat of Gibicho). Transiverat: cf. note on line 34.

|

DDSSDS Elision: iamque Ararim; Rodanumque amnes |

|||

| Atque ad praedandum cuneus dispergitur omnis. | SSDSDS | |||||

| Forte Cabillonis sedit Heriricus, et ecce | Cabillonis: Present-day Chalon sur Saône in Burgundy was called Cabillonum by Caesar (BG 7.42) but the plural form is found in Ammianus Marcellinus (14.10.3, 27.1.2).

|

Liber Regum II 18.24-25.: David autem sedebat inter duas portas; speculator vero, qui erat in fastigio portae super murum, elevans oculos vidit. . .et vociferans in culmine ait. ‘And David sat between the two gates: and the watchman that was on the top of the gate upon the wall, lifting up his eyes, saw a man running alone, and crying out he told the king.’ Statius, Thebaid 8.21-22.: Forte sedens media regni infelicis in arce/ dux Erebi. . . ‘By chance the lord of Erebus, enthroned in the midst of the fortress of his dolorous realm. . .’ 1.89-90.: inamoenum forte sedebat/ Cocyton iuxta. ‘By chance she sat beside dismyal Cocytus.’

|

|

DSSDDS | ||

| Attollens oculos speculator vociferatur: | Aeneid 4.688: illa, gravis oculos conata attollere. . . ‘She, trying to lift her heavy eyes. . .’ Statius, Thebaid 10.489-490.: iamque premunt muros--et adhuc nova funera narrat/ Amphion--miseramque intrarant protinus urbem,/ ni Megareus specula citus exclamasset ab alta:/ ‘claude, vigil, subeunt hostes, claude undique portas!’ ‘Already they are nigh the walls--and still Amphion is telling of the new disaster--and would straight have entered the hapless city, had not Megareus from a high watchtower exclaimed in haste: “Shut the gates, sentry, everywhere! The enemy comes.” ’

|

SDDSDS | ||||

| Quaenam condenso consurgit pulvere nubes? | Aeneid 4.688: illa, gravis oculos conata attollere. . . ‘She, trying to lift her heavy eyes. . .’ Statius, Thebaid 10.489-490.: iamque premunt muros--et adhuc nova funera narrat/ Amphion--miseramque intrarant protinus urbem,/ ni Megareus specula citus exclamasset ab alta:/ ‘claude, vigil, subeunt hostes, claude undique portas!’ ‘Already they are nigh the walls--and still Amphion is telling of the new disaster--and would straight have entered the hapless city, had not Megareus from a high watchtower exclaimed in haste: “Shut the gates, sentry, everywhere! The enemy comes.” ’

|

SSSSDS | ||||

| Vis inimica venit, portas iam claudite cunctas!' | 55 | Aeneid 9.33-34.: hic subitam nigro glomerari pulvere nubem/ prospiciunt Teucri. . .conclamant mole Caicus:/ ‘quis globus, o cives, caligine volvitur atra?/ ferte citi ferrum, date tela, ascendite muros,/ hostis adest, heia!’ ‘Here the Teucrians descry a sudden cloud gathering in black dust, and darkness rising on the plains. First from the rampart’s front Caicus shouts, “What mass, my countrymen, rolls onward in murky gloom? Quick, bring your swords! Give out weapons, climb the walls! The enemy is upon us!” ’ 12.150: vis inimica propinquat. ‘The enemy’s stroke draws nigh.’

|

DDSSDS | |||

| Iam tum, quid Franci fecissent, ipse sciebat | SSSSDS | |||||

| Princeps et cunctos compellat sic seniores: | SSSSDS | |||||

| Si gens tam fortis, cui nos similare nequimus, | SSSDDS | The surrender of the Franks to the Huns has set off a domino effect. The Aquitanian king Alphere uses similar reasoning to justify his surrender to Attila. | ||||

| Cessit Pannoniae, qua nos virtute putatis | Pannoniae equiv. to Hunnis

|

SDSSDS | ||||

| Huic conferre manum et patriam defendere dulcem? | 60 | Aeneid 9.690: et conferre manum et procurrere longius audent. ‘They venture to close hand to hand and to sally farther out.’ Vergil, Eclogue 1.3: nos patriae finis et dulcia linquimus arva. ‘We are leaving our country’s bounds and sweet fields.’

|

SDDSDS Elision: manum et |

|||

| Est satius, pactum faciant censumque capessant | DSDSDS | |||||

| Unica nata mihi, quam tradere pro regione | Aeneid 7.268-269.: est mihi nata, viro gentis quam iungere nostrae/ non patrio ex adyto sortes, non plurima caelo/ monstra sinunt. ‘I have a daughter whom oracles from my father’s shrine and countless prodigies from heaven do not allow me to unite to a bridegroom of our race.’

|

DDSDDS | ||||

| Non dubito: tantum pergant, qui foedera firment. | DSSSDS | |||||

| Ibant legati totis gladiis spoliati, | SSSDDS | |||||

| Hostibus insinuant, quod regis iussio mandat: | 65 | Insinuant equiv. to nuntiant

|

DDSSDS | |||

| Ut cessent vastare, rogant, quos Attila ductor, | SSDSDS | "ductor": a favorite word of Vergil's, used more than twenty times throughout the Aeneid. | ||||

| Ut solitus fuerat, blande suscepit et inquit: | DDSSDS | Attila's civilized and reasonable nature is again emphasized | ||||

| Foedera plus cupio quam proelia mittere vulgo. | DDSDDS | The Virgilian and Roman characteristics of line 8 are once again echoed as Attila accepts Hereric's terms of surrender. | ||||

| Pace quidem Huni malunt regnare, sed armis | DSSSDS | |||||

| Inviti feriunt, quos cernunt esse rebelles. | 70 | SDSSDS | ||||

| Rex ad nos veniens dextram det atque resumat.' | Aeneid 7.263-264.: ipse modo Aeneas, nostri si tanta cupido est,. . .adveniat, vultus neve exhorrescat amicos:/ pars mihi pacis erit dextram tetigisse tyranni. ‘Only let Aeneas, if so he longs for us, come in person and shrink not from friendly eyes. To me it shall be a term of the peace to have touched your sovereign’s hand.’

|

SDSSDS | ||||

| Exivit princeps asportans innumeratos | SSSSDS | Note how the meter of the heavily spondaic line (5 spondees) reflects the meaning, as Hereric, weighed down by all the treasure he carries, proceeds slowly. | ||||

| Thesauros pactumque ferit natamque reliquit. | SSDSDS | |||||

| Pergit in exilium pulcherrima gemma parentum. | DDSDDS |