Difference between revisions of "Waltharius1"

| (4 intermediate revisions by 4 users not shown) | |||

| Line 10: | Line 10: | ||

|{{Pictures|[[image:Waltharius-Line-1.png|center|thumb]]}} | |{{Pictures|[[image:Waltharius-Line-1.png|center|thumb]]}} | ||

|{{Meter|scansion=DSSSDS}} | |{{Meter|scansion=DSSSDS}} | ||

| − | | {{Comment|The opening line of the poem refers to the ancient notion "that the whole earth consists of three divisions, Europe, Asia, and Libya" (Herodotus, 2.16). Not only does it set the general stage of action for the poem | + | | {{Comment|The opening line of the poem refers to the ancient notion "that the whole earth consists of three divisions, Europe, Asia, and Libya" (Herodotus, 2.16). Not only does it set the general stage of action for the poem (which is Europe) but it is also reminiscent of the opening to Caesar's "De Bello Gallico", "Gallia est omnes divisa in patres tres" (All of Gaul is divided into three parts). The author did not know Greek, however, and most likely was not familiar with Caesar's work. Isidore of Seville's Etymologies XIV.2 was probably more influential, "Divisus est autem trifarie: e quibus una pars Asia, altera Europa, tertia Africa nuncupatur" (It is divided into three parts, one of which is called Asia, the second part Europe, the third Africa). <br />"Fratres": not only does the address "brothers" suggest the possibility of the poem's intended monastic audience, it is also one of the few times in the poem the reader is addressed directly. There is the possibility as well that "fratres" could be taken in the sense of universal brotherhood and would hence include women. |

| + | |||

| + | '''Edoardo D'Angelo (1991, p. 166-167) sees here the influence of Lucan, and quotes 9.411-417 from the Bellum Civile: "tertia pars rerum Libye, si credere famae / cuncta uelis; at, si uentos caelumque sequaris, / pars erit Europae. nec enim plus litora Nili / quam Scythicus Tanais primis a Gadibus absunt, / unde Europa fugit Libyen et litora flexu / Oceano fecere locum; sed maior in unam / orbis abit Asiam." JJTY''' '''For the wording of the first half line, the likeliest source of inspiration would be Ovid, Metamorphoses 6.372 "agitur pars tertia mundi" (noted recently by Ruben Florio [2002, p. 3]) JZ'''}} | ||

|- | |- | ||

|[[Moribus]] [[ac]] [[linguis]] [[varias]] [[et]] [[nomine]] [[gentes]] | |[[Moribus]] [[ac]] [[linguis]] [[varias]] [[et]] [[nomine]] [[gentes]] | ||

| Line 32: | Line 34: | ||

|[[Inter]] [[quas]] [[gens]] [[Pannoniae1|Pannoniae]] [[residere]] [[probatur]], | |[[Inter]] [[quas]] [[gens]] [[Pannoniae1|Pannoniae]] [[residere]] [[probatur]], | ||

| | | | ||

| − | |{{Commentary|''Pannonia'': Roman province in the north-west Balkans, according to the poet the homeland of the “Huns” (''Hunos'', line 5), a nomadic tribe that invaded Europe from the east, beginning around 370 A.D. | + | |{{Commentary|''Pannonia'': Roman province in the north-west Balkans, according to the poet the homeland of the “Huns” (''Hunos'', line 5), a nomadic tribe that invaded Europe from the east, beginning around 370 A.D. |

}} | }} | ||

| | | | ||

| Line 53: | Line 55: | ||

| | | | ||

|{{Meter|scansion=DSSDDS}} | |{{Meter|scansion=DSSDDS}} | ||

| − | |{{Comment| Indeed, the Huns were a nomadic people who flourished not by building cities but by military prowess. Note how no literary record | + | |{{Comment| Indeed, the Huns were a nomadic people who flourished not by building cities but by military prowess. Note how the Huns left no literary record nor any real archaeological one beyond military equipment.}} |

|- | |- | ||

|[[Non]] [[circumpositas]] [[solum]] [[domitans]] [[regiones]], | |[[Non]] [[circumpositas]] [[solum]] [[domitans]] [[regiones]], | ||

| Line 81: | Line 83: | ||

| | | | ||

|{{Meter|scansion=DDSSDS}} | |{{Meter|scansion=DDSSDS}} | ||

| − | |{{Comment| The poet here does not borrow any of the exact language of Aeneid 6.852 but he does not need to. The allusion to the Virgilian and Roman dictum to "spare the vanquished and crush the proud," an ideal for the imperial Roman leader, is overt. By ascribing this very Roman and ipso facto admirable trait to Attila and the Huns, the poet departs from the view in the ancient Roman's mind of the Huns the scourge of the Roman Empire. <br />This characteristic is factually accurate. Attila and the Huns destroyed many enemy armies, yet they also spared defeated foes in order to exact tribute from them. Indeed, at the very gates of Rome Attila is said to have turned back at the sight of Pope Leo I.}} | + | |{{Comment| The poet here does not borrow any of the exact language of Aeneid, most notably at 6.852 yet also at 1.257-258, but he does not need to. The allusion to the Virgilian and Roman dictum to "spare the vanquished and crush the proud," an ideal for the imperial Roman leader, is overt. By ascribing this very Roman and ipso facto admirable trait to Attila and the Huns, the poet departs from the view in the ancient Roman's mind of the Huns the scourge of the Roman Empire. <br />This characteristic is factually accurate. Attila and the Huns destroyed many enemy armies, yet they also spared defeated foes in order to exact tribute from them. Indeed, at the very gates of Rome Attila is said to have turned back at the sight of Pope Leo I.}} |

|- | |- | ||

|[[Ultra]] [[millenos]] [[fertur]] [[dominarier]] [[annos]]. | |[[Ultra]] [[millenos]] [[fertur]] [[dominarier]] [[annos]]. | ||

Latest revision as of 05:13, 16 December 2009

Introduction: the Huns (1–12)

| Tertia pars orbis, fratres, Europa vocatur, | Tertia pars orbis: as opposed to Africa and Asia, a division found as early as Herodotus (2.16). Fratres: suggests that the poem could have been read in a monastic context.

|

Lucan, De Bello Civili 9.411-412.: Tertia pars rerum Libye, si credere famae/ Cuncta velis; at, si ventos caelumque sequaris,/ Pars erit Europae. ‘Libya is the third continent of the world, if one is willing in all things to trust report; but, if you judge by the winds and the sky, you will find it to be part of Europe.’

|

DSSSDS | The opening line of the poem refers to the ancient notion "that the whole earth consists of three divisions, Europe, Asia, and Libya" (Herodotus, 2.16). Not only does it set the general stage of action for the poem (which is Europe) but it is also reminiscent of the opening to Caesar's "De Bello Gallico", "Gallia est omnes divisa in patres tres" (All of Gaul is divided into three parts). The author did not know Greek, however, and most likely was not familiar with Caesar's work. Isidore of Seville's Etymologies XIV.2 was probably more influential, "Divisus est autem trifarie: e quibus una pars Asia, altera Europa, tertia Africa nuncupatur" (It is divided into three parts, one of which is called Asia, the second part Europe, the third Africa). "Fratres": not only does the address "brothers" suggest the possibility of the poem's intended monastic audience, it is also one of the few times in the poem the reader is addressed directly. There is the possibility as well that "fratres" could be taken in the sense of universal brotherhood and would hence include women. Edoardo D'Angelo (1991, p. 166-167) sees here the influence of Lucan, and quotes 9.411-417 from the Bellum Civile: "tertia pars rerum Libye, si credere famae / cuncta uelis; at, si uentos caelumque sequaris, / pars erit Europae. nec enim plus litora Nili / quam Scythicus Tanais primis a Gadibus absunt, / unde Europa fugit Libyen et litora flexu / Oceano fecere locum; sed maior in unam / orbis abit Asiam." JJTY For the wording of the first half line, the likeliest source of inspiration would be Ovid, Metamorphoses 6.372 "agitur pars tertia mundi" (noted recently by Ruben Florio [2002, p. 3]) JZ | ||

| Moribus ac linguis varias et nomine gentes | Aeneid 8.722-723.: gentes,/ quam variae linguis, habitu tam vestis et armis. ‘Peoples as diverse in fashion of dress and arms as in tongues.’ Prudentius, Contra Orationem Symmachi 2.586-587.: discordes linguis populos et dissona cultu/ regna volens sociare Deus. . . ‘God, wishing to bring into partnership peoples of different speech and realms of discordant manners. . .’

|

DSDSDS | ||||

| Distinguens cultu, tum relligione sequestrans. | Sequestrans: “separating,” a meaning that seems to have developed from the concept of the deposit held by a sequester, the third-party arbitrator in a monetary conflict.

|

SSSDDS | "cultu": As distinguished from "religione", it probably can be translated as 'way of life', in the sense of the general style of societal customs, e.g. how they stack their hay, construct and decorate their barns, etc... | |||

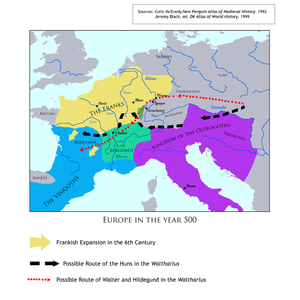

| Inter quas gens Pannoniae residere probatur, | Pannonia: Roman province in the north-west Balkans, according to the poet the homeland of the “Huns” (Hunos, line 5), a nomadic tribe that invaded Europe from the east, beginning around 370 A.D.

|

SSDDDS | ||||

| Quam tamen et Hunos plerumque vocare solemus. | 5 | DSSDDS | "Hunos": The Huns first swept into Roman consciousness when, invading from the east, they displaced the Goths, who, as detailed by Ammianus Marcellinus, ended up decimating the Roman army at the Battle of Adrianople, now Edirne in northwest Turkey, in A.D. 378. The province of Pannonia from line 4 was actually ceded to the Huns in the mid-5th century by the Eastern Roman Emperor Theodosius II after several major military defeats. | |||

| Hic populus fortis virtute vigebat et armis, | DSSDDS | Indeed, the Huns were a nomadic people who flourished not by building cities but by military prowess. Note how the Huns left no literary record nor any real archaeological one beyond military equipment. | ||||

| Non circumpositas solum domitans regiones, | Liber I Macchabeorum 1.1-2.: Et factum est postquam percussit Alexander Philippi Macedo qui primus regnavit in Graecia egressus de terra Cetthim Darium regem Persarum et Medorum constituit proelia multa et omnium obtinuit munitiones et interfecit reges terrae et pertransiit usque ad fines terrae. ‘Now it came to pass, after that Alexander the son of Philip the Macedonian, who first reigned in Greece, coming out of the land of Cethim, had overthrown Darius king of the Persians and Medes: he fought many battles, and took the strong holds of all, and slew the kings of the earth: and he went through even to the ends of the earth.’

|

SDSDDS | ||||

| Litoris oceani sed pertransiverat oras, | Liber I Macchabeorum 1.1-2.: Et factum est postquam percussit Alexander Philippi Macedo qui primus regnavit in Graecia egressus de terra Cetthim Darium regem Persarum et Medorum constituit proelia multa et omnium obtinuit munitiones et interfecit reges terrae et pertransiit usque ad fines terrae. ‘Now it came to pass, after that Alexander the son of Philip the Macedonian, who first reigned in Greece, coming out of the land of Cethim, had overthrown Darius king of the Persians and Medes: he fought many battles, and took the strong holds of all, and slew the kings of the earth: and he went through even to the ends of the earth.’

|

DDSSDS | "oceani": 'Oceanus' in traditional mythology was the son of Uranus and Gaia and the personification of the great river that encircled the known world. Though the extent to which a Carolingian or near-Carolingian monk would have known geography beyond antiquity's understanding of it is unclear, the very same section of Isidore's Etymologies referenced in line 1 explicitly mentions Oceanus as encircling the globe. The Huns were a people of the inland steppes and plains. At the height of its power, the Hunnic Empire stretched from the Caspian and Black Seas to the North Sea and even the Adriatic, but never all the way to the Atlantic Ocean. | |||

| Foedera supplicibus donans sternensque rebelles. | Aeneid 6.851-852.: tu regere imperio populos, Romane, memento/ (hae tibi erunt artes), pacique imponere morem,/ parcere subiectis et debellare superbos. ‘You, Roman, be sure to rule the world (be these your arts), to crown peace with justice, to spare the vanquished and to crush the proud.’

|

DDSSDS | The poet here does not borrow any of the exact language of Aeneid, most notably at 6.852 yet also at 1.257-258, but he does not need to. The allusion to the Virgilian and Roman dictum to "spare the vanquished and crush the proud," an ideal for the imperial Roman leader, is overt. By ascribing this very Roman and ipso facto admirable trait to Attila and the Huns, the poet departs from the view in the ancient Roman's mind of the Huns the scourge of the Roman Empire. This characteristic is factually accurate. Attila and the Huns destroyed many enemy armies, yet they also spared defeated foes in order to exact tribute from them. Indeed, at the very gates of Rome Attila is said to have turned back at the sight of Pope Leo I. | |||

| Ultra millenos fertur dominarier annos. | 10 | Fertur: the subject is populus. Dominarier: archaic form for the passive infinitive (here of a deponent), frequent in poetry of all periods.

|

SSSDDS | This is a case of hyperbole by the author. Perhaps in the medieval mind the name Huns is a reference to an amalgamation of particular antique peripheral invaders, which might explain the reference in line 12 to Attila's wish to renew the "antiquos triumphos." In actuality the Hunnic empire came into existence in the west around 370 when they destroyed a tribe of Alans, and eventually petered out around 469 at the death of Dengizik, the succesor of Attila's son Ellak. Beginning here, but continued throughout the poem, the poet treats the Huns not as barbarians invaders but a strong, proud people with an illustrious history. By putting the Huns on relative par with the Romans (c. line 11) in the way they rule and duration of their "imperium", he strengthens the foundations of his own civilization. Were the Franks and other western European peoples defeated by a mere marauding hoard, there would be no nobility in recalling such story. However, given that the Huns are set up as a broad and powerful civilization, that they were eventually overcome becomes so much more impressive and heroic genesis of the poet's own times. | ||

| Attila rex quodam tulit illud tempore regnum, | Attila: Ruler of the Huns, first with his brother Bleda, from 434 to 455, then alone until 453 A.D. Tulit equiv. togessit

|

DSDSDS | ||||

| Impiger antiquos sibimet renovare triumphos. | Renovare: infinitive following impiger (“eager”); cf. Hor. Carm. 4.14.22.

|

DSDDDS | "antiquos triumphos": c. note on line 10; most likely "antiquos" should be read as 'ancient' or 'ancestral' as opposed to 'old', which would lend itself to the grandeur with which the poet tries to infuse the Huns. Attila is not attempting to rekindle the fame of his own younger days, but the younger days of his people. |