Difference between revisions of "Waltharius513"

| (14 intermediate revisions by 3 users not shown) | |||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

| + | ===Gunther and his companions approach Walther’s camp; Hagen unsuccessfully tries to dissuade the king from attacking it (513–531)=== | ||

{| | {| | ||

|- | |- | ||

| Line 17: | Line 18: | ||

| | | | ||

|{{Meter|scansion=DDSSDS}} | |{{Meter|scansion=DDSSDS}} | ||

| − | | | + | | {{Comment|Cornipedem: horse (literally, "horn-foot"). The hoof was considered to be made of horn similar to the material of an antler. Cato and Virgil both use the word of hooves; interestingly, in was also applied to birds' beaks, warts, and even, according to Pliny, skin over the eye. MCD [It would be good to consider whether the borrowing from Prudentius is solely verbal or whether the original context may shed light upon the new one in the Waltharius. JZ}} |

|- | |- | ||

|[[Exultansque]] [[animis]] [[frustra]] [[sic]] [[fatur1|fatur]] [[ad]] [[auras]]: | |[[Exultansque]] [[animis]] [[frustra]] [[sic]] [[fatur1|fatur]] [[ad]] [[auras]]: | ||

|515 | |515 | ||

| | | | ||

| − | |{{Parallel|'' | + | |{{Parallel|''Aeneid'' 2.386: ''exultans animisque. . .'' ‘Flushed with courage. . .’ 11.491: ''exsultateque animis.'' ‘He exults in courage.’ 11.556: ''ita ad aethera fatur.'' ‘He cries thus to the heavens.’ |

}} | }} | ||

| | | | ||

|{{Meter|scansion=SDSSDS|elision=exultansque animis}} | |{{Meter|scansion=SDSSDS|elision=exultansque animis}} | ||

| − | | | + | |{{Comment|frustra: "in vain." Emphasizes Gunther's vainglory again. MCD}} |

|- | |- | ||

|[[Accelerate]], [[viri1|viri]], [[iam]] [[nunc]] [[capietis]] [[euntem]], | |[[Accelerate]], [[viri1|viri]], [[iam]] [[nunc]] [[capietis]] [[euntem]], | ||

| Line 44: | Line 45: | ||

| | | | ||

|{{Meter|scansion=DDSDDS|elision=H-ELISION: numquam hodie; hodie effugit}} | |{{Meter|scansion=DDSDDS|elision=H-ELISION: numquam hodie; hodie effugit}} | ||

| − | | | + | |{{Comment|Gunther combines Walther with the Huns in his mind to justify his unprovoked attack, imagining Walther the agent of the "theft" of treaty-money from the Franks. An alternative explanation is that he actually blames Walther for stealing from his lord (Attila, in this case) and so feels no compunction about taking back what was his. This implies a level of loyalty to Germanic oaths which he has not previously displayed, however. MCD [In this case the original context in the third Eclogue contrasts amusingly on what happens in the Waltharius and would be worth discussing. JZ]}} |

|- | |- | ||

|[[Inclitus]] [[at]] [[Hagano]] [[contra1|contra]] [[mox]] [[reddidit]] [[ista2|ista]]: | |[[Inclitus]] [[at]] [[Hagano]] [[contra1|contra]] [[mox]] [[reddidit]] [[ista2|ista]]: | ||

| Line 86: | Line 87: | ||

| | | | ||

|{{Meter|scansion=SDDSDS}} | |{{Meter|scansion=SDDSDS}} | ||

| − | | | + | |{{Comment|The Hunnish battle early in the poem, before Walther speaks with Hildegund about escape, places the reader or listener's sympathies firmly with Hagan, since we too have "seen" Walther fight. MCD}} |

|- | |- | ||

|[[Vidi]] [[Pannonias1|Pannonias]] [[acies]], [[cum]] [[bella]] [[cierent]] | |[[Vidi]] [[Pannonias1|Pannonias]] [[acies]], [[cum]] [[bella]] [[cierent]] | ||

| | | | ||

| | | | ||

| − | |{{Parallel|'' | + | |{{Parallel|''Aeneid'' 1.541: ''bella cient.'' ‘They stir up wars.’ Statius, ''Thebaid ''11.487: ''cum bella cieret. . .'' ‘When he made war. . .’ |

}} | }} | ||

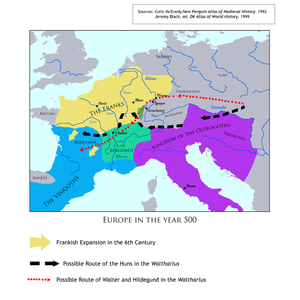

| − | | | + | |{{Pictures|[[Image:Europe500.png|center|thumb]]}} |

|{{Meter|scansion=SDDSDS}} | |{{Meter|scansion=SDDSDS}} | ||

| | | | ||

| Line 104: | Line 105: | ||

| | | | ||

|{{Meter|scansion=DSSSDS|elision=contra Aquilonares; sive Australes}} | |{{Meter|scansion=DSSSDS|elision=contra Aquilonares; sive Australes}} | ||

| − | | | + | | {{Comment|Since the beginning of the poem is spent establishing that all of western Europe fears the Huns, Hagan's assertion that he is greater than them carries considerable weight. MCD}} |

|- | |- | ||

|[[Illic]] [[Waltharius]] [[propria]] [[virtute]] [[coruscus]] | |[[Illic]] [[Waltharius]] [[propria]] [[virtute]] [[coruscus]] | ||

| Line 112: | Line 113: | ||

| | | | ||

|{{Meter|scansion=SDDSDS}} | |{{Meter|scansion=SDDSDS}} | ||

| − | | | + | | {{Comment|"coruscus": see note to l. 453. Once again the poet uses images of light; this time Walther's manliness shines for the whole world. The exact repetition of the adjective "coruscus" from the ferryman's description also calls back to mind the image of the perfect warrior which Gunther has conveniently forgotten in order to convince his men that Walther is "imbellus" (see l. 486). MCD}} |

|- | |- | ||

|[[Hostibus]] [[invisus]], [[sociis1|sociis]] [[mirandus]] [[obibat]]: | |[[Hostibus]] [[invisus]], [[sociis1|sociis]] [[mirandus]] [[obibat]]: | ||

| | | | ||

| | | | ||

| − | |{{Parallel|'' | + | |{{Parallel|''Aeneid'' 6.167:'' lituo pugnas insignis obibat et hasta. '' ‘He braved the fray, glorious for clarion and spear alike.’ |

}} | }} | ||

| | | | ||

| Line 126: | Line 127: | ||

| | | | ||

| | | | ||

| − | |{{Parallel|'' | + | |{{Parallel|''Aeneid'' 6.134-135: ''bis nigra videre/ Tartara. . . '' ‘Twice to see black Tartarus. . .’ |

}} | }} | ||

| | | | ||

|{{Meter|scansion=DSDSDS}} | |{{Meter|scansion=DSDSDS}} | ||

| − | | | + | | {{Comment|The Waltharius-poet uses a Virgilian formula here, which may be significant in the effort to place the poem's religious loyalties. Though little is known specifically of continental Germanic paganism, it is generally assumed to bear some similarity to Scandinavian cults, since related tribes colonized the areas during the period of migration following the fall of Rome. According to what is known of Scandinavian beliefs, a warrior who fell in battle might hope that his soul would fly to Valhalla, a feasting hall in the realm of the gods, where great warriors awaited the final battle, Ragnarok, at the end of the world. Those who passed away from sickness or accident traveled instead to Hel, in an underworld which resembles Roman Tartarus or Christian Hell much more closely than Valhalla. A warrior who perished in battle with Walther, according to such a belief system, was much more fortunate than one who died safe in his bed. Little trace of such an ethos is evident in Hagan's warning, however; he treats death as a fate to be avoided. In this sense, Gunther's later mockery of Hagan's caution perhaps is justified in terms of Germanic religion; that Gunther's world-view is clearly denigrated, however, suggests that the Waltharius-poet wishes to associate all death with the darkness of Hel, stripping it of any (pagan) glory. For a further discussion of Germanic religion, see Rudolf Simek's chapter in ''Early Germanic Literature and Culture,'' ed. Brian Murdoch and Malcolm Read (2004).}} |

|- | |- | ||

|[[O]] [[rex1|rex]] [[et]] [[comites1|comites]], [[experto]] [[credite]], [[quantus]] | |[[O]] [[rex1|rex]] [[et]] [[comites1|comites]], [[experto]] [[credite]], [[quantus]] | ||

| | | | ||

| | | | ||

| − | |{{Parallel|: '' | + | |{{Parallel|: ''Aeneid'' 11.283-284: ''experto credite quantus/ in clipeum adsurgat, quo turbine torqueat hastam. '' ‘Trust one who has experienced it, how huge he looms above his shield, with what whirlwind he hurls his spear.’ |

}} | }} | ||

| | | | ||

|{{Meter|scansion=SDSSDS}} | |{{Meter|scansion=SDSSDS}} | ||

| − | | | + | |{{Comment|"comites": Hagan remembers his fellow warriors and vassals to Gunther. Together, they form [what Tacitus called JZ] a comitatus, a war-band with cohesion and standards of loyalty which also bind Hagan. A betrayal of Gunther for Hagan would also amount to a betrayal of his companions. Hagan's later attempt to abdicate the situation, though perhaps intended to avoid breaking either oath, still leaves them without his protection. Appealing to them, too, is another way to appeal to Gunther, though such an appeal might dangerously undermine his loyalty. MCD}} |

|- | |- | ||

|[[In]] [[clipeum]] [[surgat]], [[quo]] [[turbine]] [[torqueat]] [[hastam]].' | |[[In]] [[clipeum]] [[surgat]], [[quo]] [[turbine]] [[torqueat]] [[hastam]].' | ||

| | | | ||

| | | | ||

| − | |{{Parallel|: '' | + | |{{Parallel|: ''Aeneid'' 11.283-284: ''experto credite quantus/ in clipeum adsurgat, quo turbine torqueat hastam. '' ‘Trust one who has experienced it, how huge he looms above his shield, with what whirlwind he hurls his spear.’ |

}} | }} | ||

| | | | ||

|{{Meter|scansion=DSSDDS}} | |{{Meter|scansion=DSSDDS}} | ||

| − | | | + | | {{Comment|The poet's use of parallel structure emphasizes Walther's great skill as a balanced warrior: he has no weaknesses. MCD}} |

|- | |- | ||

|[[sed1|Sed]] [[dum]] [[Guntharius]] [[male]] [[sana]] [[mente]] [[gravatus]] | |[[sed1|Sed]] [[dum]] [[Guntharius]] [[male]] [[sana]] [[mente]] [[gravatus]] | ||

|530 | |530 | ||

| | | | ||

| − | |{{Parallel|'' | + | |{{Parallel|''Aeneid'' 4.8: ''male sana. . . '' ‘Much distraught. . .’ |

}} | }} | ||

| | | | ||

|{{Meter|scansion=SDDSDS}} | |{{Meter|scansion=SDDSDS}} | ||

| − | | | + | |{{Comment|Gunther is "weighed down with an unhealthy mind." The poet is probably not suggesting that Gunther is insane, but he certainly does behave irrationally and obsessively with regard to Walther and the treasure he carries, sacrificing all his best men in the attempt to defeat him. Avarice itself, in the poet's mind, might be a kind of insanity. This is connected to the Platonic idea that the man ruled by his passions is a slave, devoid of true power, excluded from the "kingship" of rationality, which would probably have been familiar to the Waltharius-poet through Boethius. MCD [A citation is needed, at least to Boethius, to justify the mention of Plato. JZ] |

| + | |||

| + | Perhaps this would be more akin to Stoicism rather than Platonism? [JJTY]}} | ||

|- | |- | ||

|[[Nequaquam]] [[flecti]] [[posset]], [[castris1|castris]] [[propriabant]]. | |[[Nequaquam]] [[flecti]] [[posset]], [[castris1|castris]] [[propriabant]]. | ||

| Line 174: | Line 177: | ||

|[[Waltharius489|« previous]] | |[[Waltharius489|« previous]] | ||

|{{Outline| | |{{Outline| | ||

| − | * Prologue | + | * [[WalthariusPrologue|Prologue]] |

| − | * Introduction: the Huns (1–12) | + | * [[Waltharius1|Introduction: the Huns (1–12)]] |

* The Huns (13–418) | * The Huns (13–418) | ||

| − | ** The Franks under Gibich surrender to Attila, giving Hagen as a hostage (13–33) | + | ** [[Waltharius13|The Franks under Gibich surrender to Attila, giving Hagen as a hostage (13–33)]] |

| − | ** The Burgundians under Hereric surrender to Attila, giving Hildegund as a hostage (34–74) | + | ** [[Waltharius34|The Burgundians under Hereric surrender to Attila, giving Hildegund as a hostage (34–74)]] |

| − | ** The Aquitainians under Alphere surrender to Attila, giving Walther as a hostage (75–92) | + | ** [[Waltharius75|The Aquitainians under Alphere surrender to Attila, giving Walther as a hostage (75–92)]] |

| − | ** Experience of the hostages at Attila’s court (93–115) | + | ** [[Waltharius93|Experience of the hostages at Attila’s court (93–115)]] |

| − | ** Death of Gibich, flight of Hagen (116–122) | + | ** [[Waltharius116|Death of Gibich, flight of Hagen (116–122)]] |

| − | ** Attila’s queen Ospirin advises her husband to ensure Walther’s loyalty by arranging a marriage (123–141) | + | ** [[Waltharius123|Attila’s queen Ospirin advises her husband to ensure Walther’s loyalty by arranging a marriage (123–141)]] |

| − | ** Walther rejects Attila’s offer of a bride (142–169) | + | ** [[Waltharius142|Walther rejects Attila’s offer of a bride (142–169)]] |

| − | ** Walther leads the army of the Huns to victory in battle (170–214) | + | ** [[Waltharius170|Walther leads the army of the Huns to victory in battle (170–214)]] |

** The Escape (215–418) | ** The Escape (215–418) | ||

| − | *** Walther returns from battle and encounters Hildegund (215–255) | + | *** [[Waltharius215|Walther returns from battle and encounters Hildegund (215–255)]] |

| − | *** Walther reveals to Hildegund his plans for escaping with Attila’s treasure (256–286) | + | *** [[Waltharius256|Walther reveals to Hildegund his plans for escaping with Attila’s treasure (256–286)]] |

| − | *** Walther hosts a luxurious banquet for Attila’s court; eventually all his intoxicated guests fall asleep (287–323) | + | *** [[Waltharius287|Walther hosts a luxurious banquet for Attila’s court; eventually all his intoxicated guests fall asleep (287–323)]] |

| − | *** Flight of Walther and Hildegund from Attila’s court (324–357) | + | *** [[Waltharius324|Flight of Walther and Hildegund from Attila’s court (324–357)]] |

| − | *** The following day, the escape of Walther and Hildegund is discovered by Ospirin (358–379) | + | *** [[Waltharius358|The following day, the escape of Walther and Hildegund is discovered by Ospirin (358–379)]] |

| − | *** Attila is infuriated and vows revenge on Walther, but can find no one willing to dare to pursue him, even for a large reward (380–418) | + | *** [[Waltharius380|Attila is infuriated and vows revenge on Walther, but can find no one willing to dare to pursue him, even for a large reward (380–418)]] |

* The Single Combats (419–1061) | * The Single Combats (419–1061) | ||

** Diplomacy (419–639) | ** Diplomacy (419–639) | ||

| − | *** Flight of Walther and Hildegund to the area of Worms (419–435) | + | *** [[Waltharius419|Flight of Walther and Hildegund to the area of Worms (419–435)]] |

| − | *** Gunther, King of the Franks, learns of Walther’s presence on his territory and, despite Hagen’s warnings, decides to pursue him for his treasure (436–488) | + | *** [[Waltharius436|Gunther, King of the Franks, learns of Walther’s presence on his territory and, despite Hagen’s warnings, decides to pursue him for his treasure (436–488)]] |

| − | *** Walther makes his camp in a mountainous area and goes to sleep (489–512) | + | *** [[Waltharius489|Walther makes his camp in a mountainous area and goes to sleep (489–512)]] |

*** '''Gunther and his companions approach Walther’s camp; Hagen unsuccessfully tries to dissuade the king from attacking it (513–531)''' | *** '''Gunther and his companions approach Walther’s camp; Hagen unsuccessfully tries to dissuade the king from attacking it (513–531)''' | ||

| − | *** Hildegund sees the Franks approaching and wakes Walther, who calms her fears and prepares for battle; he recognizes Hagen from a distance (532–571) | + | *** [[Waltharius532|Hildegund sees the Franks approaching and wakes Walther, who calms her fears and prepares for battle; he recognizes Hagen from a distance (532–571)]] |

| − | *** Hagen persuades Gunther to try diplomacy before using force (571–580) | + | *** [[Waltharius571|Hagen persuades Gunther to try diplomacy before using force (571–580)]] |

| − | *** Camalo is sent as a messenger to Walther, who offers to make Gunther a gift in return for allowing his passage (581–616) | + | *** [[Waltharius581|Camalo is sent as a messenger to Walther, who offers to make Gunther a gift in return for allowing his passage (581–616)]] |

| − | *** Hagen counsels Gunther to accept the offer, but Gunther rejects this advice, calling him a coward. Insulted, Hagen goes off to a nearby hill (617–639) | + | *** [[Waltharius617|Hagen counsels Gunther to accept the offer, but Gunther rejects this advice, calling him a coward. Insulted, Hagen goes off to a nearby hill (617–639)]] |

** Combat (640–1061) | ** Combat (640–1061) | ||

| − | *** 1st single combat: Camalo is sent back to Walther, who slays him (640–685) | + | *** [[Waltharius640|1st single combat: Camalo is sent back to Walther, who slays him (640–685)]] |

| − | *** 2nd single combat: Walther slays Kimo/Scaramund, Camalo’s nephew (686–719) | + | *** [[Waltharius686|2nd single combat: Walther slays Kimo/Scaramund, Camalo’s nephew (686–719)]] |

| − | *** Gunther encourages his men (720–724) | + | *** [[Waltharius720|Gunther encourages his men (720–724)]] |

| − | *** 3rd single combat: Walther slays Werinhard, a descendant of the Trojan Pandarus (725–753) | + | *** [[Waltharius725|3rd single combat: Walther slays Werinhard, a descendant of the Trojan Pandarus (725–753)]] |

| − | *** 4th single combat: Walther slays the Saxon Ekivrid, after an exchange of insults (754–780) | + | *** [[Waltharius754|4th single combat: Walther slays the Saxon Ekivrid, after an exchange of insults (754–780)]] |

| − | *** 5th single combat: Walther slays Hadawart, after an exchange of insults (781–845) | + | *** [[Waltharius781|5th single combat: Walther slays Hadawart, after an exchange of insults (781–845)]] |

| − | *** Hagen sees his nephew Patavrid going off to fight Walther and laments the evil wreaked on mankind by greed (846–877) | + | *** [[Waltharius846|Hagen sees his nephew Patavrid going off to fight Walther and laments the evil wreaked on mankind by greed (846–877)]] |

| − | *** 6th single combat: after trying to dissuade him from fighting, Walther slays Patavrid (878–913) | + | *** [[Waltharius878|6th single combat: after trying to dissuade him from fighting, Walther slays Patavrid (878–913)]] |

| − | *** 7th single combat: Walther slays Gerwitus (914–940) | + | *** [[Waltharius914|7th single combat: Walther slays Gerwitus (914–940)]] |

| − | *** Gunther again encourages his men, giving Walther some time to rest (941–961) | + | *** [[Waltharius941|Gunther again encourages his men, giving Walther some time to rest (941–961)]] |

| − | *** 8th single combat: Walther is shorn of his hair by Randolf, whom he then slays (962–981) | + | *** [[Waltharius962|8th single combat: Walther is shorn of his hair by Randolf, whom he then slays (962–981)]] |

| − | *** Walther is attacked by Eleuthir/Helmnot, assisted by Trogus, Tanastus, and Gunther; he slays all but Gunther (981–1061) | + | *** [[Waltharius981|Walther is attacked by Eleuthir/Helmnot, assisted by Trogus, Tanastus, and Gunther; he slays all but Gunther (981–1061)]] |

* The Final Combat (1062–1452) | * The Final Combat (1062–1452) | ||

| − | ** Gunther tries to persuade Hagen to help him to defeat Waltharius; remembering his wounded honor, Hagen refuses (1062–1088) | + | ** [[Waltharius1062|Gunther tries to persuade Hagen to help him to defeat Waltharius; remembering his wounded honor, Hagen refuses (1062–1088)]] |

| − | ** Hagen changes his mind and agrees to help Gunther, but advises that they must lie low wait until Walther comes down from the mountains into open ground (1089–1129) | + | ** [[Waltharius1089|Hagen changes his mind and agrees to help Gunther, but advises that they must lie low wait until Walther comes down from the mountains into open ground (1089–1129)]] |

| − | ** Walther decides to spend the night in the mountains. He rematches the severed heads with the bodies of his victims, prays for their souls, then sleeps (1130–1187) | + | ** [[Waltharius1130|Walther decides to spend the night in the mountains. He rematches the severed heads with the bodies of his victims, prays for their souls, then sleeps (1130–1187)]] |

| − | ** The following day, Walther and Hildegund set out from the mountains, taking the horses and arms of the defeated warriors (1188–1207) | + | ** [[Waltharius1188|The following day, Walther and Hildegund set out from the mountains, taking the horses and arms of the defeated warriors (1188–1207)]] |

| − | ** Hildegund perceives Gunther and Hagen approaching to attack; the king addresses Walther (1208–1236) | + | ** [[Waltharius1208|Hildegund perceives Gunther and Hagen approaching to attack; the king addresses Walther (1208–1236)]] |

| − | ** Walther ignores Gunther and pleads with Hagen to remember the bond of their childhood friendship; Hagen counters that Walther has already broken their faith by slaying Patavrid (1237–1279) | + | ** [[Waltharius1237|Walther ignores Gunther and pleads with Hagen to remember the bond of their childhood friendship; Hagen counters that Walther has already broken their faith by slaying Patavrid (1237–1279)]] |

| − | ** The fight begins and continues for seven hours; Gunther foolishly tries to retrieve a thrown spear from the ground near Walther and is only saved from death by Hagen’s brave intervention (1280–1345) | + | ** [[Waltharius1280|The fight begins and continues for seven hours; Gunther foolishly tries to retrieve a thrown spear from the ground near Walther and is only saved from death by Hagen’s brave intervention (1280–1345)]] |

| − | ** Walther challenges Hagen; he severs Gunther’s leg, but Hagen again saves the king’s life (1346–1375) | + | ** [[Waltharius1346|Walther challenges Hagen; he severs Gunther’s leg, but Hagen again saves the king’s life (1346–1375)]] |

| − | ** Hagen cuts off Walther’s right hand; Walther gouges out one of Hagen’s eyes and, cutting open his cheek, knocks out four teeth (1376–1395) | + | ** [[Waltharius1376|Hagen cuts off Walther’s right hand; Walther gouges out one of Hagen’s eyes and, cutting open his cheek, knocks out four teeth (1376–1395)]] |

| − | ** Having wounded each other, the warriors end the battle, drink together, and engage in a friendly exchange of humorous taunt (1396–1442) | + | ** [[Waltharius1396|Having wounded each other, the warriors end the battle, drink together, and engage in a friendly exchange of humorous taunt (1396–1442)]] |

| − | ** The warriors return to their respective homes; Walther marries Hildegund and eventually becomes king of the Aquitainians (1443–1452) | + | ** [[Waltharius1443|The warriors return to their respective homes; Walther marries Hildegund and eventually becomes king of the Aquitainians (1443–1452)]] |

| − | * Epilogue (1453–1456)}} | + | * [[Waltharius1453|Epilogue (1453–1456)]]}} |

| | | | ||

|[[Waltharius532|next »]] | |[[Waltharius532|next »]] | ||

Latest revision as of 15:23, 17 December 2009

Gunther and his companions approach Walther’s camp; Hagen unsuccessfully tries to dissuade the king from attacking it (513–531)

| Ast ubi Guntharius vestigia pulvere vidit, | Georgics 3.171: summo vestigia pulvere signent. ‘Let them print their tracks on the surface of the dust.’ Statius, Thebaid 6.640: raraque non fracto vestigia pulvere pendent. ‘The rare footsteps hover and leave the dust unbroken.’

|

DDSDDS | ||||

| Cornipedem rapidum saevis calcaribus urget, | Prudentius, Psychomachia 253-254.: talia vociferans rapidum calcaribus urget/ cornipedem. ‘Thus exclaiming she spurs on her swift charger and flies wildling along with loose rein.’ Statius, Thebaid 11.452-453.: saevis calcaribus urgent/ immeritos. ‘With savage goads they incite their innocent teams.’

|

DDSSDS | Cornipedem: horse (literally, "horn-foot"). The hoof was considered to be made of horn similar to the material of an antler. Cato and Virgil both use the word of hooves; interestingly, in was also applied to birds' beaks, warts, and even, according to Pliny, skin over the eye. MCD [It would be good to consider whether the borrowing from Prudentius is solely verbal or whether the original context may shed light upon the new one in the Waltharius. JZ | |||

| Exultansque animis frustra sic fatur ad auras: | 515 | Aeneid 2.386: exultans animisque. . . ‘Flushed with courage. . .’ 11.491: exsultateque animis. ‘He exults in courage.’ 11.556: ita ad aethera fatur. ‘He cries thus to the heavens.’

|

SDSSDS Elision: exultansque animis |

frustra: "in vain." Emphasizes Gunther's vainglory again. MCD | ||

| Accelerate, viri, iam nunc capietis euntem, | DDSDDS | |||||

| Numquam hodie effugiet, furata talenta relinquet.' | Furata: passive in sense, though from a deponent.

|

Eclogue 3.49: numquam hodie effugies. ‘This time you won’t get away!’

|

DDSDDS Elision: H-ELISION: numquam hodie; hodie effugit |

Gunther combines Walther with the Huns in his mind to justify his unprovoked attack, imagining Walther the agent of the "theft" of treaty-money from the Franks. An alternative explanation is that he actually blames Walther for stealing from his lord (Attila, in this case) and so feels no compunction about taking back what was his. This implies a level of loyalty to Germanic oaths which he has not previously displayed, however. MCD [In this case the original context in the third Eclogue contrasts amusingly on what happens in the Waltharius and would be worth discussing. JZ] | ||

| Inclitus at Hagano contra mox reddidit ista: | DDSSDS | |||||

| Unum dico tibi, regum fortissime, tantum: | SDSSDS | |||||

| Si totiens tu Waltharium pugnasse videres | 520 | Videres equiv. to vidisses

|

DSDSDS | |||

| Atque nova totiens, quotiens ego, caede furentem, | Aeineid 2.499-500.: vidi ipse furentem/ caede Neoptolemum. ‘I myself saw Neoptolemus, mad with slaughter.’ 8.695: arva nova Neptunia caede rubescunt. Neptune’s fields redden with strange slaughter.’ 10.514-515.: te, Turne, superbum/ caede nova. . . ‘You, Turnus, still flushed with fresh slaughter. . .’

|

DDDDDS | ||||

| Numquam tam facile spoliandum forte putares. | SDDSDS | The Hunnish battle early in the poem, before Walther speaks with Hildegund about escape, places the reader or listener's sympathies firmly with Hagan, since we too have "seen" Walther fight. MCD | ||||

| Vidi Pannonias acies, cum bella cierent | Aeneid 1.541: bella cient. ‘They stir up wars.’ Statius, Thebaid 11.487: cum bella cieret. . . ‘When he made war. . .’

|

SDDSDS | ||||

| Contra Aquilonares sive Australes regiones: | Aquilonares equiv. to Aquilonias

|

DSSSDS Elision: contra Aquilonares; sive Australes |

Since the beginning of the poem is spent establishing that all of western Europe fears the Huns, Hagan's assertion that he is greater than them carries considerable weight. MCD | |||

| Illic Waltharius propria virtute coruscus | 525 | SDDSDS | "coruscus": see note to l. 453. Once again the poet uses images of light; this time Walther's manliness shines for the whole world. The exact repetition of the adjective "coruscus" from the ferryman's description also calls back to mind the image of the perfect warrior which Gunther has conveniently forgotten in order to convince his men that Walther is "imbellus" (see l. 486). MCD | |||

| Hostibus invisus, sociis mirandus obibat: | Aeneid 6.167: lituo pugnas insignis obibat et hasta. ‘He braved the fray, glorious for clarion and spear alike.’

|

DSDSDS | ||||

| Quisquis ei congressus erat, mox Tartara vidit. | Aeneid 6.134-135: bis nigra videre/ Tartara. . . ‘Twice to see black Tartarus. . .’

|

DSDSDS | The Waltharius-poet uses a Virgilian formula here, which may be significant in the effort to place the poem's religious loyalties. Though little is known specifically of continental Germanic paganism, it is generally assumed to bear some similarity to Scandinavian cults, since related tribes colonized the areas during the period of migration following the fall of Rome. According to what is known of Scandinavian beliefs, a warrior who fell in battle might hope that his soul would fly to Valhalla, a feasting hall in the realm of the gods, where great warriors awaited the final battle, Ragnarok, at the end of the world. Those who passed away from sickness or accident traveled instead to Hel, in an underworld which resembles Roman Tartarus or Christian Hell much more closely than Valhalla. A warrior who perished in battle with Walther, according to such a belief system, was much more fortunate than one who died safe in his bed. Little trace of such an ethos is evident in Hagan's warning, however; he treats death as a fate to be avoided. In this sense, Gunther's later mockery of Hagan's caution perhaps is justified in terms of Germanic religion; that Gunther's world-view is clearly denigrated, however, suggests that the Waltharius-poet wishes to associate all death with the darkness of Hel, stripping it of any (pagan) glory. For a further discussion of Germanic religion, see Rudolf Simek's chapter in Early Germanic Literature and Culture, ed. Brian Murdoch and Malcolm Read (2004). | |||

| O rex et comites, experto credite, quantus | : Aeneid 11.283-284: experto credite quantus/ in clipeum adsurgat, quo turbine torqueat hastam. ‘Trust one who has experienced it, how huge he looms above his shield, with what whirlwind he hurls his spear.’

|

SDSSDS | "comites": Hagan remembers his fellow warriors and vassals to Gunther. Together, they form [what Tacitus called JZ] a comitatus, a war-band with cohesion and standards of loyalty which also bind Hagan. A betrayal of Gunther for Hagan would also amount to a betrayal of his companions. Hagan's later attempt to abdicate the situation, though perhaps intended to avoid breaking either oath, still leaves them without his protection. Appealing to them, too, is another way to appeal to Gunther, though such an appeal might dangerously undermine his loyalty. MCD | |||

| In clipeum surgat, quo turbine torqueat hastam.' | : Aeneid 11.283-284: experto credite quantus/ in clipeum adsurgat, quo turbine torqueat hastam. ‘Trust one who has experienced it, how huge he looms above his shield, with what whirlwind he hurls his spear.’

|

DSSDDS | The poet's use of parallel structure emphasizes Walther's great skill as a balanced warrior: he has no weaknesses. MCD | |||

| Sed dum Guntharius male sana mente gravatus | 530 | Aeneid 4.8: male sana. . . ‘Much distraught. . .’

|

SDDSDS | Gunther is "weighed down with an unhealthy mind." The poet is probably not suggesting that Gunther is insane, but he certainly does behave irrationally and obsessively with regard to Walther and the treasure he carries, sacrificing all his best men in the attempt to defeat him. Avarice itself, in the poet's mind, might be a kind of insanity. This is connected to the Platonic idea that the man ruled by his passions is a slave, devoid of true power, excluded from the "kingship" of rationality, which would probably have been familiar to the Waltharius-poet through Boethius. MCD [A citation is needed, at least to Boethius, to justify the mention of Plato. JZ]

Perhaps this would be more akin to Stoicism rather than Platonism? [JJTY] | ||

| Nequaquam flecti posset, castris propriabant. | Propiabant equiv. to appropinquabant

|

SSSSDS |