Difference between revisions of "Waltharius962"

(→8th single combat: Walther is shorn of his hair by Randolf, whom he then slays (962–981)) |

|||

| (One intermediate revision by one other user not shown) | |||

| Line 8: | Line 8: | ||

|{{Pictures|[[image:Waltharius-Lines-962–1062.png|center|thumb]]}} | |{{Pictures|[[image:Waltharius-Lines-962–1062.png|center|thumb]]}} | ||

|{{Meter|scansion=DSSSDS}} | |{{Meter|scansion=DSSSDS}} | ||

| − | | {{Comment|'''athleta:''' This noun was used in a figural sense in philosophical discourse (see Seneca, De providentia / dialogi I, 2.2.5) and later also used in Christian discourse, where it acquired a connotation associated with martyrdom. See especially Ambrose, De paradiso 12.55: “unde et Paulus quasi bonus athleta non solum ictus aduersantium potestatum uitare cognouerat, uerum etiam aduersantes ferire” (“therefore Paul also knew how | + | | {{Comment|'''athleta:''' This noun was used in a figural sense in philosophical discourse (see Seneca, De providentia / dialogi I, 2.2.5) and later also used in Christian discourse, where it acquired a connotation associated with martyrdom. See especially Ambrose, De paradiso 12.55: “unde et Paulus quasi bonus athleta non solum ictus aduersantium potestatum uitare cognouerat, uerum etiam aduersantes ferire” (“therefore Paul also knew how not only to avoid the blows of the opposing forces like a good athlete, but also to give blows to his adversaries”). Cf. the description of Walther in 1046 and its usage by Walther to describe Hagan in 1411. See also the note on “agonem” in 1025. [JJTY] |

'''Randolf:''' Wagner notes that in Old High German, the form should be Rantolf instead of Randolf. He claims that this is an example of Late High German and has parallels in Notker the Stammerer, allowing for a relatively late, tenth century dating of the poem. See Wagner 1992, p. 118. [JJTY]}} | '''Randolf:''' Wagner notes that in Old High German, the form should be Rantolf instead of Randolf. He claims that this is an example of Late High German and has parallels in Notker the Stammerer, allowing for a relatively late, tenth century dating of the poem. See Wagner 1992, p. 118. [JJTY]}} | ||

| Line 38: | Line 38: | ||

|{{PicturesCont}} | |{{PicturesCont}} | ||

|{{Meter|scansion=DSSDDS}} | |{{Meter|scansion=DSSDDS}} | ||

| − | | {{Comment|'''Wielandia fabrica:''' For the tale of Wayland, see J. Grimm, Deutsche Mythologie, Göttingen: Dieterichsche Buchhandlung, 1844, vol. 1, pp. 349-352. As a mythological smith, Wayland is analogous to Homer’s Hephaestus (see especially Iliad 18.368-384 and 468-477) and Virgil’s | + | | {{Comment|'''Wielandia fabrica:''' For the tale of Wayland, see J. Grimm, Deutsche Mythologie, Göttingen: Dieterichsche Buchhandlung, 1844, vol. 1, pp. 349-352. As a mythological smith, Wayland is analogous to Homer’s Hephaestus (see especially Iliad 18.368-384 and 468-477) and Virgil’s Vulcan (Aeneid 8.439-453.), who forge the armor for the epic’s respective heroes. Althof (1905, ad loc.) remarks that the tale, originating in Lower Germany, was already widespread across Northern Europe by the end of the seventh century. Cf. the Waldere fragments (2-3), where the sword Miming is mentioned as fabricated by Wayland. Beowulf (405-406 and 454-455) mentions Beowulf’s byrnie as a “work of Wayland” (“Welandes geweorc”). In J. Bradley, “Sorceror or Symbol?– Weland the Smith in Anglo-Saxon Sculpture and Verse,” Pacific Coast Philology 25:1 (1990), pp. 39-48, at 39-40, King Alfred is cited as an early source for Wayland, whose translation of Boethius’ De consolatione philosophiae renders the Roman name Fabricius as Wayland, going on to comment on Wayland as the ideal craftsman. This translation was probably made by an association of the name Fabricius with the Latin noun “faber” (“worksman”), and designed to make the passage more relevant to the Anglo-Saxon reader (see for this theory C.A. Spinage, Myths and Mysteries of Wayland Smith, Oxfordshire: Wychwood Press, 2003, pp. 61-62). Note, moreover, the same association of “faber” and Wayland in this very passage of the Waltharius: “Wielandia fabrica.” Bradley (ibid., p. 41; see also H. Ritter-Schaumburg, Der Schmied Weland. Forschungen zum historischen Kern der Sage von Wieland dem Schmied, Hildesheim: Georg Olms Verlag, 1999, pp.147-169) also quotes from the Norse Thithrek’s Saga, which says that the highest praise a smith’s product can receive, is to be said to have been made by Völund (i.e. the Norse equivalent of Wayland). In fact, there is historical evidence that many smiths on the continent were named after Wayland (Bradley 1990, p. 42). |

In Bradley 1990, pp. 42-43, a convincing reconstruction of the spread of the myth is made. Bradley asserts that the origins of the Wayland story are Greco-Roman – that it is in fact an adaptation of the story of Daedalus made as early as the fifth century A.D. along the Danube in modern-day Austria. The myth was then further developed by an historical event: the vita of St. Severin (written by Eugippius in the seventh century A.D.) records an uprising of a number of captive smiths near Linz around 480 A.D., who had taken the queen’s son hostage. The myth spread to Scandinavia and England from there. | In Bradley 1990, pp. 42-43, a convincing reconstruction of the spread of the myth is made. Bradley asserts that the origins of the Wayland story are Greco-Roman – that it is in fact an adaptation of the story of Daedalus made as early as the fifth century A.D. along the Danube in modern-day Austria. The myth was then further developed by an historical event: the vita of St. Severin (written by Eugippius in the seventh century A.D.) records an uprising of a number of captive smiths near Linz around 480 A.D., who had taken the queen’s son hostage. The myth spread to Scandinavia and England from there. | ||

| Line 62: | Line 62: | ||

|{{PicturesCont}} | |{{PicturesCont}} | ||

|{{Meter|scansion=DDDSDS}} | |{{Meter|scansion=DDDSDS}} | ||

| − | | {{Comment|'''Ille tamen subito stupefactus corda pavore:''' After Gunther | + | | {{Comment|'''Ille tamen subito stupefactus corda pavore:''' After Gunther completes his encouraging speech to his disheartened men and opens the attack on Walther, this hexameter reflects the change of pace and the recommencement of the action, not just by its words (“subito,” “suddenly”), but also by its almost entirely dactylic meter. [JJTY]}} |

| − | }} | ||

|- | |- | ||

|[[Munimen]] [[clipei]] [[obiecit]] [[mentemque]] [[recepit]]; | |[[Munimen]] [[clipei]] [[obiecit]] [[mentemque]] [[recepit]]; | ||

| | | | ||

| | | | ||

| − | |{{Parallel|Prudentius, ''Psychomachia'' 503: ''clipeum obiectasset.'' ‘She put her shield in the way.’ '' | + | |{{Parallel|Prudentius, ''Psychomachia'' 503: ''clipeum obiectasset.'' ‘She put her shield in the way.’ ''Aeneid'' 12.377: ''clipeo obiecto. . .'' ‘With his shield before him. . .’ 10.899: ''mentemque recepit.'' ‘He regained his senses.’ |

}} | }} | ||

|{{PicturesCont}} | |{{PicturesCont}} | ||

| Line 86: | Line 85: | ||

|970 | |970 | ||

| | | | ||

| − | |{{Parallel|'' | + | |{{Parallel|''Aeneid'' 10.474: ''magnis emittit viribus hastam. '' ‘He hurls his spear with all his strength.’ |

}} | }} | ||

|{{PicturesCont}} | |{{PicturesCont}} | ||

| Line 157: | Line 156: | ||

| | | | ||

| | | | ||

| − | |{{Parallel|'' | + | |{{Parallel|''Aeneid'' 2.50; 5.500: ''validis. . .viribus. . .'' ‘With mighty force. . .’ 1.193: ''corpora fundat humi. ‘''He stretches the bodies on the ground.’ 11.665: ''quot humi morientia corpora fundis? '' ‘How many bodies do you lay low on the earth?’ |

}} | }} | ||

|{{PicturesCont}} | |{{PicturesCont}} | ||

| Line 166: | Line 165: | ||

| | | | ||

| | | | ||

| − | |{{Parallel|'' | + | |{{Parallel|''Aeneid'' 10.490-491.: ''quem Turnus super adsistens. . .inquit. . .'' ‘Standing over him, Turnus cries. . .’ Prudentius, ''Psychomachia ''155: ''quam super adsistens Patientia. . .inquit. . .'' ‘Standing over her, Long-Suffering cries. . .’ |

}} | }} | ||

|{{PicturesCont}} | |{{PicturesCont}} | ||

Latest revision as of 20:51, 17 December 2009

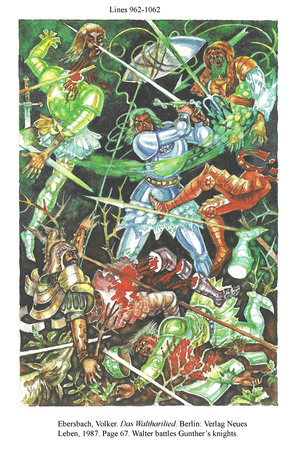

8th single combat: Walther is shorn of his hair by Randolf, whom he then slays (962–981)

| Ecce repentino Randolf athleta caballo | DSSSDS | athleta: This noun was used in a figural sense in philosophical discourse (see Seneca, De providentia / dialogi I, 2.2.5) and later also used in Christian discourse, where it acquired a connotation associated with martyrdom. See especially Ambrose, De paradiso 12.55: “unde et Paulus quasi bonus athleta non solum ictus aduersantium potestatum uitare cognouerat, uerum etiam aduersantes ferire” (“therefore Paul also knew how not only to avoid the blows of the opposing forces like a good athlete, but also to give blows to his adversaries”). Cf. the description of Walther in 1046 and its usage by Walther to describe Hagan in 1411. See also the note on “agonem” in 1025. [JJTY]

Randolf: Wagner notes that in Old High German, the form should be Rantolf instead of Randolf. He claims that this is an example of Late High German and has parallels in Notker the Stammerer, allowing for a relatively late, tenth century dating of the poem. See Wagner 1992, p. 118. [JJTY] | ||||

| Praevertens reliquos hunc importunus adivit | Prudentius, Psychomachia 228-229.: hostis nunc surgit ab oris/ inportunus. ‘The foe arises now from the shores to trouble us.’

|

SDSSDS | ||||

| Ac mox ferrato petiit sub pectore conto. | Prudentius, Psychomachia 116: impatiensque morae conto petit. ‘Irked by her hanging back, she hurls a pike at her.’ 122-123.: sub ipsum/ defertur stomachum. ‘It hits the very stomach.’

|

SSDSDS | ||||

| Et nisi duratis Wielandia fabrica giris | 965 | Wielandia fabrica: “the workmanship of Wieland,” a legendary smith, comparable to Hephaestus or Daedalus, in German mythology. Cf. line 264 on the lorica.

|

Prudentius, Psychomachia 124-125.: sed resilit duro loricae excussa repulsu./ provida nam Virtus conserto adamante trilicem/ induerat thoraca umeris. ‘But it is struck off by the resistance of a hard cuirass, and rebounds; for the Virtue had prudently put on her shoulders a three-ply corselet of mail impenetrable.’

|

DSSDDS | Wielandia fabrica: For the tale of Wayland, see J. Grimm, Deutsche Mythologie, Göttingen: Dieterichsche Buchhandlung, 1844, vol. 1, pp. 349-352. As a mythological smith, Wayland is analogous to Homer’s Hephaestus (see especially Iliad 18.368-384 and 468-477) and Virgil’s Vulcan (Aeneid 8.439-453.), who forge the armor for the epic’s respective heroes. Althof (1905, ad loc.) remarks that the tale, originating in Lower Germany, was already widespread across Northern Europe by the end of the seventh century. Cf. the Waldere fragments (2-3), where the sword Miming is mentioned as fabricated by Wayland. Beowulf (405-406 and 454-455) mentions Beowulf’s byrnie as a “work of Wayland” (“Welandes geweorc”). In J. Bradley, “Sorceror or Symbol?– Weland the Smith in Anglo-Saxon Sculpture and Verse,” Pacific Coast Philology 25:1 (1990), pp. 39-48, at 39-40, King Alfred is cited as an early source for Wayland, whose translation of Boethius’ De consolatione philosophiae renders the Roman name Fabricius as Wayland, going on to comment on Wayland as the ideal craftsman. This translation was probably made by an association of the name Fabricius with the Latin noun “faber” (“worksman”), and designed to make the passage more relevant to the Anglo-Saxon reader (see for this theory C.A. Spinage, Myths and Mysteries of Wayland Smith, Oxfordshire: Wychwood Press, 2003, pp. 61-62). Note, moreover, the same association of “faber” and Wayland in this very passage of the Waltharius: “Wielandia fabrica.” Bradley (ibid., p. 41; see also H. Ritter-Schaumburg, Der Schmied Weland. Forschungen zum historischen Kern der Sage von Wieland dem Schmied, Hildesheim: Georg Olms Verlag, 1999, pp.147-169) also quotes from the Norse Thithrek’s Saga, which says that the highest praise a smith’s product can receive, is to be said to have been made by Völund (i.e. the Norse equivalent of Wayland). In fact, there is historical evidence that many smiths on the continent were named after Wayland (Bradley 1990, p. 42).

In Bradley 1990, pp. 42-43, a convincing reconstruction of the spread of the myth is made. Bradley asserts that the origins of the Wayland story are Greco-Roman – that it is in fact an adaptation of the story of Daedalus made as early as the fifth century A.D. along the Danube in modern-day Austria. The myth was then further developed by an historical event: the vita of St. Severin (written by Eugippius in the seventh century A.D.) records an uprising of a number of captive smiths near Linz around 480 A.D., who had taken the queen’s son hostage. The myth spread to Scandinavia and England from there. The oldest reference to the myth is made in the decoration of the Franks Casket, which shows a smith, a woman, and a maid in the smithy, a decapitated body lying on the floor and a man hunting birds. For a more detailed description of the Franks Casket (dated around 700 A.D.), see P.W. Souers, “The Wayland Scene on the Franks Casket,” in Speculum 18:1 (1943), pp. 104-111. Interestingly, the scene of Wayland on the Franks Casket is juxtaposed with a scene of the Magi – a rather similar juxtaposition of mythological and Christian elements to the one we find in the Waltharius. In attempting to explain Wayland’s role in (Anglo-Saxon) Christianity, Bradley (1990, pp. 45-47) quotes from an exegetical text on 2 Kings 24.12-14 from Venerable Bede, which allegorizes the smiths in Babylonian Captivity as supplying the followers of the faith with weapons. Bradley then argues that the link with Wayland could easily have been made in an homiletic context to make such biblical passages more palatable for the Anglo-Saxon audience – especially because Wayland was commonly found among themes of exile; see for instance the opening lines of the Anglo-Saxon poem Deor, a reflection on misfortune from the tenth century and preserved in the Exeter Book, which present Wayland as a man in bitter exile. In a similar manner, one could allegorize that Walther has been given armor by Wayland to protect himself from the vices of avarice, anger, and pride that besiege him. Furthermore, Walther, like Wayland, has suffered the unjust fate of exile and was kept in captivity by a king until he devised his own escape (Wayland was captured by king Niðhad and made a cripple). By the simple reference of “Wielandia fabrica,” the poet of the Waltharius has managed to blend seamlessly and unobtrusively two traditions of exile that would have been at the fore-front of the mind of a medieval reader. [JJTY] | |

| Obstaret, spisso penetraverit ilia ligno. | Ligno equiv. to conto

|

Prudentius, Psychomachia 124-125.: sed resilit duro loricae excussa repulsu./ provida nam Virtus conserto adamante trilicem/ induerat thoraca umeris. ‘But it is struck off by the resistance of a hard cuirass, and rebounds; for the Virtue had prudently put on her shoulders a three-ply corselet of mail impenetrable.’

|

SSDDDS | |||

| Ille tamen subito stupefactus corda pavore | Ille: Waltharius Corda: accusative of respect

|

DDDSDS | Ille tamen subito stupefactus corda pavore: After Gunther completes his encouraging speech to his disheartened men and opens the attack on Walther, this hexameter reflects the change of pace and the recommencement of the action, not just by its words (“subito,” “suddenly”), but also by its almost entirely dactylic meter. [JJTY] | |||

| Munimen clipei obiecit mentemque recepit; | Prudentius, Psychomachia 503: clipeum obiectasset. ‘She put her shield in the way.’ Aeneid 12.377: clipeo obiecto. . . ‘With his shield before him. . .’ 10.899: mentemque recepit. ‘He regained his senses.’

|

SDSSDS Elision: clipei obiecit |

Munimen clipei obiecit mentemque recepit: Notice how the elision of the “i” of “clipei” causes a resounding clash with the ictus in the first syllable of the following word (“obiecit”), imitating the sword’s blow on the shield. [JJTY] | |||

| Nec tamen et galeam fuerat sumpsisse facultas. | Fuerat sumpsisse facultas equiv. to sumere potuit, cf. line 960.

|

DDDSDS | ||||

| Francus at emissa gladium nudaverat hasta | 970 | Aeneid 10.474: magnis emittit viribus hastam. ‘He hurls his spear with all his strength.’

|

DSDSDS | |||

| Et feriens binos Aquitani vertice crines | Binos…crines: “two locks of hair”

|

Prudentius, Psychomachia 506-507.: vix in cute summa/ praestringens paucos tenui de vulnere laedit/ cuspis Avaritiae. ‘Only a few did Greed’s javelin touch, grazing them with a slight wound not skin-deep.’ Aeneid 4.698-699.: vertice crinem/ abstulerat. ‘She had taken from her head the lock.’ Statius, Thebaid 344-345.: addit acerba sonum Teumesi e vertice crinem/ incutiens. ‘From Teumesus’ height she sends her shrill cry, and shakes her locks.’

|

|

vertice crines / abrasit: Beck (1908, ad loc.) remarks that the cutting of hair was a dishonorable act for a free man, quoting Tacitus, Germania 19, where an adulteress is shorn and subsequently chased out of her home. D’Angelo (1998, ad 979) remarks that the tonsure, besides being practiced by monks, was imposed on persons of the lower classes such as slaves or prisoners of war, making this an especially dishonorable act for a warrior or nobleman. This explains Walther’s fierce outburst before he slays Randolf in 979 (“Ecce pro calvitio capitis te vertice fraudo,” “I take your head from you as payment for my baldness”), and also Helmnod’s taunting in 991: “ferro tibi finis, calve, sub isto!” (“You, bald head! With this spear the end has come for you!”)

The passage may also contain a reminiscence to the biblical story of Samson and Delilah (Judges 14-16), in which Samson loses his strength as a result of being shorn. This is not the case with Walther, however, who only grows fiercer, much to his opponent’s dismay. Given the similar phrasing of Virgil, Aeneid 4.698-9 (“vertice crinem / abstulerat,” “she had taken from her head the lock”), the astute reader may be led to fear for Waltharius’ life at this point, since Virgil’s passage describes Iris being sent down by Juno to cut of a lock of Dido’s hair to grant her passage to the underworld. [JJTY] | ||

| Abrasit, sed forte cutem praestringere summam | Prudentius, Psychomachia 506-507.: vix in cute summa/ praestringens paucos tenui de vulnere laedit/ cuspis Avaritiae. ‘Only a few did Greed’s javelin touch, grazing them with a slight wound not skin-deep.’ Aeneid 4.698-699.: vertice crinem/ abstulerat. ‘She had taken from her head the lock.’ Statius, Thebaid 344-345.: addit acerba sonum Teumesi e vertice crinem/ incutiens. ‘From Teumesus’ height she sends her shrill cry, and shakes her locks.’

|

SSDSDS | ||||

| Non licuit, rursumque alium vibraverat ictum | DSDSDS Elision: rursumque alium |

|||||

| Et praeceps animi directo obstamine scuti | Praeceps animi: “hasty”

|

Aeneid 9.685: praeceps animi. . . ‘Reckless at heart. . .’

|

SDSSDS Elision: directo obstamine |

|||

| Impegit calibem, nec quivit viribus ullis | 975 | Aeneid 6.147-148.: non viribus ullis/ vincere. . .poteris. ‘With no force will you avail to win it.’ 12.782: viribus haud ullis valuit discludere morsus. ‘By no strength could he unlock the bite.’

|

SDSSDS | |||

| Elicere. Alpharides retro, se fulminis instar | Elicere equiv. to revellere Retro: with fudit Se…excutiens equiv. to emicans

|

Ovid, Ars Amatoria 3.490: fulminis instar habent. ‘They hold what is like a thunderbolt.’

|

DDSSDS Elision: elicere Alpharides |

|||

| Excutiens, Francum valida vi fudit ad arvum | Aeneid 2.50; 5.500: validis. . .viribus. . . ‘With mighty force. . .’ 1.193: corpora fundat humi. ‘He stretches the bodies on the ground.’ 11.665: quot humi morientia corpora fundis? ‘How many bodies do you lay low on the earth?’

|

DSDSDS | ||||

| Et super assistens pectus conculcat et inquit: | Aeneid 10.490-491.: quem Turnus super adsistens. . .inquit. . . ‘Standing over him, Turnus cries. . .’ Prudentius, Psychomachia 155: quam super adsistens Patientia. . .inquit. . . ‘Standing over her, Long-Suffering cries. . .’

|

DSSSDS | Et super assistens pectus conculcat et inquit: The phrasing reminds the reader of a similar death scene in Virgil, Aeneid 10.490-491 (“Quem Turnus super adsistens .. inquit,” “Standing over him, Turnus says”) where Turnus slays Pallas. It is interesting that Waltharius first receives a description similar to that of the unlikeable character Mezentius (see 960-961) and is now implicitly compared to Turnus as he ruthlessly slays the young Pallas. Is the reader’s favor meant to slowly shift toward the camp of Gunther, now no longer bent on looting but on receiving vengeance for their lost comrades? [JJTY] | |||

| En pro calvitio capitis te vertice fraudo, | SDDSDS | |||||

| Ne fiat ista tuae de me iactantia sponsae.' | 980 | DDSSDS | Ne fiat ista tuae de me iactantia sponsae: Tacitus (Germania 7) notes that Germanic kings are particularly prone to brag to their wife and children, who are their greatest audience: “Hi cuique sanctissimi testes, hi maximi laudatores” (“They are to each their most sacred witnesses, they are their greatest glorifiers”). Cf. Walther’s defiant speech in 562-3: “Hinc nullus rediens uxori dicere Francus / Praesumet se impune gazae quid tollere tantae” (“No Frank, returning from this place, will dare to tell / His wife that he, unharmed, took any of this treasure”). [JJTY] |