Difference between revisions of "Waltharius981"

(→Walther is attacked by Eleuthir/Helmnot, assisted by Trogus, Tanastus, and Gunther; he slays all but Gunther (981–1061)) |

|||

| (14 intermediate revisions by 2 users not shown) | |||

| Line 18: | Line 18: | ||

|{{PicturesCont}} | |{{PicturesCont}} | ||

|{{Meter|scansion=SSSSDS|hiatus=pugnae Helmnod}} | |{{Meter|scansion=SSSSDS|hiatus=pugnae Helmnod}} | ||

| − | | {{Comment|Helmnod: see the note below on line 1008. JJTY}} | + | | {{Comment|'''Helmnod:''' see the note below on line 1008. JJTY}} |

|- | |- | ||

|[[Insertum]] [[triplici]] [[gestabat]] [[fune]] [[tridentem]], | |[[Insertum]] [[triplici]] [[gestabat]] [[fune]] [[tridentem]], | ||

| Line 105: | Line 105: | ||

|{{PicturesCont}} | |{{PicturesCont}} | ||

|{{Meter|scansion=SDDSDS}} | |{{Meter|scansion=SDDSDS}} | ||

| − | | {{Comment|'''iaculorum:''' On flying tree snakes, see Pliny, Naturalis historia 8.14.36, and 8.35.85 for the iaculus in particular: “iaculum ex arborum ramis vibrari, nec pedibus tantum pavendas serpentes, sed ut missile volare tormento” (“...the iaculus balances on tree branches, nor need feet alone fear snakes, since it flies like a javelin from a sling”). This account may then have been used by Lucan in Bellum Civile 9.720 (“iaculique volucres,” “and flying iaculi”) and 9.823, | + | | {{Comment|'''iaculorum:''' On flying tree snakes, see Pliny, Naturalis historia 8.14.36, and 8.35.85 for the iaculus in particular: “iaculum ex arborum ramis vibrari, nec pedibus tantum pavendas serpentes, sed ut missile volare tormento” (“...the iaculus balances on tree branches, nor need feet alone fear snakes, since it flies like a javelin from a sling”). This account may then have been used by Lucan in Bellum Civile 9.720 (“iaculique volucres,” “and flying iaculi”) and 9.823: “Ecce procul saevus sterilis se robore trunci / Torsit et immisit (iaculum vocat Africa) serpens / Perque caput Pauli transactaque tempora fugit” (“Lo! from afar a fierce serpent hurls itself with the strength of its trunk that has no appendages (Africa calls it the ‘iaculus’) and takes flight through Paulus’ head and pierces his temples”). ['''Ben Tipping's as yet unpublished 'Lucan's Cato' makes much of the imagery and symbolism of the snakes in book IX of the 'Pharsalia'. He suggests the "iaculus" along with the many other snakes assailing Cato's forces in the Libyan desert mock the Stoic sapiens, e.g. how the 'dispsas', whose name implies avarice, at 9.737-60 quite causes one of the soldiers to be consumed by such a burning thirst that he cuts his veins in order to drink his own blood. I bring it up because Gunther's avarice is what caused him to attack Walther in the first place, and the snakes, at least in Lucan, are symbolic of such un-Stoic (and un-Christian) greed.''' [AP]] This topic is expanded on by the fourth century writer Ammianus Marcellinus, who remarks in his Historiae (22.15.27) that Egypt has a rich variety of snakes, among which is mentioned the “acontia,” without adding any further description. Lucan’s account is used and quoted by Isidore in the Etymologiae sive Origines 12.29: “Iaculus serpens volans. De quo Lucanus: ‘Iaculique volucres.’ Exiliunt enim in arboribus, et dum aliquod animal obvium fuerit, iactant se super eum et perimunt; unde et iaculi dicti sunt” (“Iaculus the flying snake. About which Lucan says: ‘and the flying snakes.’ For they scale up trees, and when any animal comes on their path, they throw themselves on top of it and kill it; and that is why they are called javelins”). Isidore’s account also bears close resemblance to the fifth century account of Solinus, Collectanea rerum memorabilium 27.30: “iaculi arbores subeunt, e quibus vi maxima turbinati penetrant animal quodcumque obvium fortuna fecerit” (“iaculi go to trees, from which they hurl themselves with the greatest force and pierce any animal that fortune has set on their path”). See D’Angelo 1991, pp. 177-179 for an overview of the different opinions of scholars concerning the source used by the poet of the Waltharius. D’Angelo concludes that Lucan’s passage is echoed but not used as a source in this instance, and that Solinus is the more likely candidate for source material because “quod genus aspidis” (“which kind of snake” – it is difficult to know whether the poet of the Waltharius meant a snake in general by using “aspis” or the “asp” in particular) of line 993 in the Waltharius closely resembles Solinus 27.31: “Plures diuersaeque aspidum species” (“[there are] many and diverse kinds of asps”). However, when discussing asps, Isidore (12.13-14) mentions the following kinds (among others): “Dipsas, genus aspidis” (“Dipsas, a kind of asp”) and “Hypnalis, genus aspidis” (“Hypnalis, a kind of asp”). The passage from the Waltharius therefore sticks closer to Isidore by using the genitive singular of “aspis.” |

| − | Althof (1905, ad loc.) remarks: “Der Vergleich des Speeres mit einer Schlange ist echt germanisch.” Though this may be true, the very name attributed to this kind of serpent – iaculus, going back to the Greek ἀκοντίας (see Nicander, Theriaka 491), meaning “javelin” – evidences that this comparison was already made in Greco-Roman times. See also Aelianus, De natura animalium 6.18: “ἤδη δὲ καὶ ἀκοντίων δίκην ἑαυτόν τις μεθίησι καὶ ἐπιφέρεται, καὶ τό γε ὄνομα ἐξ οὗ δρᾷ ἔχει” | + | Althof (1905, ad loc.) remarks: “Der Vergleich des Speeres mit einer Schlange ist echt germanisch.” Though this may be true, the very name attributed to this kind of serpent – iaculus, going back to the Greek ἀκοντίας (see Nicander, Theriaka 491), meaning “javelin” – evidences that this comparison was already made in Greco-Roman times. See also Aelianus, De natura animalium 6.18: “ἤδη δὲ καὶ ἀκοντίων δίκην ἑαυτόν τις μεθίησι καὶ ἐπιφέρεται, καὶ τό γε ὄνομα ἐξ οὗ δρᾷ ἔχει” (“Indeed a certain kind [i.e. of snake] launches itself and flies in the manner of javelins, and acquires its name from its action”). [JJTY]}} |

|- | |- | ||

|[[quod2|Quod]] [[genus1|genus]] [[aspidis]] [[ex]] [[alta]] [[sese]] [[arbore]] [[tanto]] | |[[quod2|Quod]] [[genus1|genus]] [[aspidis]] [[ex]] [[alta]] [[sese]] [[arbore]] [[tanto]] | ||

| Line 133: | Line 133: | ||

|{{PicturesCont}} | |{{PicturesCont}} | ||

|{{Meter|scansion=DSDSDS}} | |{{Meter|scansion=DSDSDS}} | ||

| − | | {{Comment|'''Quid moror?''' This phrase exposes the snake comparison for what it is: a poetic technique to heighten the tension in an exciting moment (Helmnod/Eleuthir has just thrown a lance towards Walther) by supplying unnecessary background information; the phrase “quid moror” (“why do I delay any longer?”) then signals the return to the action. [JJTY]}} | + | | {{Comment|'''Quid moror?''' This phrase exposes the snake comparison for what it is: a poetic technique to heighten the tension in an exciting moment (Helmnod/Eleuthir has just thrown a lance towards Walther) by supplying unnecessary background information; the phrase “quid moror” (“why do I delay any longer?”) then signals the return to the action. [JJTY] <br /> Cf. line 92: "Sed quis plus remorer?" (But why stretch out my tale?), in which the poet accelerates the pace of the tale by eliding over the details of Walther's own surrender to Attila. [AP]}} |

|- | |- | ||

|[[Clamorem]] [[Franci1|Franci]] [[tollunt]] [[saltusque]] [[resultat]], | |[[Clamorem]] [[Franci1|Franci]] [[tollunt]] [[saltusque]] [[resultat]], | ||

| | | | ||

| | | | ||

| − | |{{Parallel|'' | + | |{{Parallel|''Aeneid'' 10.262: ''clamorem ad sidera tollunt.'' ‘They raise a shout to the sky.’ 11.622:'' clamorem tollunt.'' ‘They raise a shout.’ 8.305: ''consonat omne nemus strepitu collesque resultant.'' ‘The woodland rings with the clamour, and the hills resound.’ |

}} | }} | ||

|{{PicturesCont}}{{Pictures|<gallery widths="180px" heights="120px" perrow="2"> | |{{PicturesCont}}{{Pictures|<gallery widths="180px" heights="120px" perrow="2"> | ||

| Line 251: | Line 251: | ||

|{{PicturesCont}} | |{{PicturesCont}} | ||

|{{Meter|scansion=DDSSDS}} | |{{Meter|scansion=DDSSDS}} | ||

| − | | {{Comment|'''Nonus Eleuthir erat, Helmnod cognomine dictus:''' According to Schröder (1931, pp. 150-151), Eleuthir is a possible Langobardic double version of the name (Eleuthir vs. Leuthir). It is a Hellenized version of (He)leuthere/Liuthere, analogous to the Greek | + | | {{Comment|'''Nonus Eleuthir erat, Helmnod cognomine dictus:''' According to Schröder (1931, pp. 150-151), Eleuthir is a possible Langobardic double version of the name (Eleuthir vs. Leuthir). It is a Hellenized version of (He)leuthere/Liuthere, analogous to the Greek ἐλεύθερος (“free”), resulting in a word-play with "Frank," which also means "free." Schröder (ibid.) also remarks that one would expect Eleuthir to be the nickname, not Helmnod. Helmnod, according to Wagner (1992, pp. 119-120), is a composite name meaning “helmet-blow,” from the Old High German (h)nod. It is possible that the mention of two names of the same person reflects different (oral) traditions of the Waltharius. [JJTY]}} |

|- | |- | ||

|[[Argentina]] [[quidem]] [[decimum]] [[dant]] [[oppida]] [[Trogum]], | |[[Argentina]] [[quidem]] [[decimum]] [[dant]] [[oppida]] [[Trogum]], | ||

| Line 354: | Line 354: | ||

|1020 | |1020 | ||

| | | | ||

| − | |{{Parallel|'' | + | |{{Parallel|''Aeneid'' 3.140: ''linquebant dulcis animas.'' ‘Men gave up their sweet lives.’ 9.475: ''miserae calor ossa reliquit. '' ‘Warmth left her hapless frame.’ |

}} | }} | ||

|{{PicturesCont}} | |{{PicturesCont}} | ||

| Line 366: | Line 366: | ||

|{{PicturesCont}} | |{{PicturesCont}} | ||

|{{Meter|scansion=DSSSDS|elision=haerentem in|hiatus=Trogum haerentem}} | |{{Meter|scansion=DSSSDS|elision=haerentem in|hiatus=Trogum haerentem}} | ||

| − | | | + | | {{Comment|'''haerentem in fune:''' D’Angelo (1991, p. 171) quotes as a parallel to this passage Lucan, Bellum Civile 5.514 (“Rupibus exesis haerentem fune carinam,” “a ship hanging on to a rope in a hewn cave”) and 3.628 (“Haesissem, quamvis amens, in fune retentus,” “I would have hung on, although I was out of my mind, hanging onto the rope”). [JJTY]}} |

|- | |- | ||

|[[qui3|Qui]] [[subito1|subito]] [[attonitus]] [[recidentis]] [[morte]] [[sodalis]] | |[[qui3|Qui]] [[subito1|subito]] [[attonitus]] [[recidentis]] [[morte]] [[sodalis]] | ||

| Line 380: | Line 380: | ||

| | | | ||

| | | | ||

| − | |{{Parallel|'' | + | |{{Parallel|''Aeneid'' 11.271: ''horribili visu portenta sequuntur.'' ‘Portents of dreadful view pursue me.’ |

<br />''Georgics'' 3.141-142.: ''acri/ carpere prata fuga. . .'' ‘To scour the meadows in swift flight. . .’ | <br />''Georgics'' 3.141-142.: ''acri/ carpere prata fuga. . .'' ‘To scour the meadows in swift flight. . .’ | ||

}} | }} | ||

| Line 391: | Line 391: | ||

| | | | ||

|{{Parallel|''Georgics'' 3.141-142.: ''acri/ carpere prata fuga. . .'' ‘To scour the meadows in swift flight. . .’ | |{{Parallel|''Georgics'' 3.141-142.: ''acri/ carpere prata fuga. . .'' ‘To scour the meadows in swift flight. . .’ | ||

| − | <br />'' | + | <br />''Aeneid'' 12.484: ''fugam cursu temptavit equorum. '' ‘He strove by running to match the flihgt of the horses.’ |

}} | }} | ||

|{{PicturesCont}} | |{{PicturesCont}} | ||

| Line 400: | Line 400: | ||

|1025 | |1025 | ||

| | | | ||

| − | |{{Parallel|'' | + | |{{Parallel|''Aeneid'' 5.15: ''colligere arma iubet.'' ‘He bids them gather in the tackling.’ |

}} | }} | ||

|{{PicturesCont}} | |{{PicturesCont}} | ||

| Line 421: | Line 421: | ||

| | | | ||

|{{Parallel|''Aeneid'' 12.707: ''armaque deposuere umeris. '' ‘They took off the armour from their shoulders.’ | |{{Parallel|''Aeneid'' 12.707: ''armaque deposuere umeris. '' ‘They took off the armour from their shoulders.’ | ||

| − | <br />'' | + | <br />''Aeneid'' 6.192: ''maximus heros. . .'' ‘The great hero. . .’ |

}} | }} | ||

|{{PicturesCont}} | |{{PicturesCont}} | ||

| Line 464: | Line 464: | ||

| | | | ||

| | | | ||

| − | |{{Parallel|'' | + | |{{Parallel|''Aeneid'' 12.896-897.: ''saxum circumspicit ingens. . .ille manu raptum trepida torquebat in hostem.'' ‘He glances round and sees a huge stone. . .With hurried grasp, he seized and hurled it at his foe.’ 12.266: ''adversos telum contorsit in hostes. '' ‘Darting forward, he hurled his spear full against the foe.’ |

}} | }} | ||

|{{PicturesCont}} | |{{PicturesCont}} | ||

| Line 502: | Line 502: | ||

|{{PicturesCont}} | |{{PicturesCont}} | ||

|{{Meter|scansion=DDDDDS}} | |{{Meter|scansion=DDDDDS}} | ||

| − | | | + | | {{Comment|'''vacuaverat aedem:''' I.e.: he unsheathed his sword. A prime example of the kenning or circumlocution typical of Germanic literature. [JJTY]}} |

|- | |- | ||

|[[Atque]] [[ardens]] [[animis]] [[vibratu]] [[terruit]] [[auras]], | |[[Atque]] [[ardens]] [[animis]] [[vibratu]] [[terruit]] [[auras]], | ||

| Line 525: | Line 525: | ||

|{{Commentary|''Habitum equiv. to animum'' | |{{Commentary|''Habitum equiv. to animum'' | ||

}} | }} | ||

| − | |{{Parallel|'' | + | |{{Parallel|''Aeneid'' 9.311: ''ante annos animumque gerens curamque virilem. . .'' ‘With a man’s mind and a spirit beyond his years. . .’ |

}} | }} | ||

|{{PicturesCont}} | |{{PicturesCont}} | ||

| Line 538: | Line 538: | ||

|{{PicturesCont}} | |{{PicturesCont}} | ||

|{{Meter|scansion=SSDSDS}} | |{{Meter|scansion=SSDSDS}} | ||

| − | | {{Comment|'''Nec manes ridere videns:''' This is a puzzling phrase. Is it possible that “manes” is metonymically used for “death” and is here used with “ridere” to personify death? This would seem likely, because of the similar phrase in Hagan’s speech in 849-850: “Aspice mortem, / Qualiter arridet!” (“Look at Death, / How it is grinning!”) Althof (1905, ad loc.) compares this passage to “Dominus | + | | {{Comment|'''Nec manes ridere videns:''' This is a puzzling phrase. Is it possible that “manes” is metonymically used for “death” and is here used with “ridere” to personify death? This would seem likely, because of the similar phrase in Hagan’s speech in 849-850: “Aspice mortem, / Qualiter arridet!” (“Look at Death, / How it is grinning!”); see also 1327: “Quem quoque continuo esurienti porgeret Orco” (“Him too he would have sent straightway to hungry Orcus”). Althof (1905, ad loc.) compares this passage to “Dominus Blitero” in the Ysengrimus / Reinardus Vulpes (5.1100): “Hanc tibi dono gigam, pagana est utpote porrum / Osseaque ut dominus Blitero, sume, vide!” (“I give you this fiddle, as common as a leek / and as bony as lord Blitero – see, take it!”). According to J. Grimm, Deutsche Mythologie, Göttingen: Dieterichsche Buchhandlung, 1844, vol. 2, pp. 849-850, the name “Blitero” could be etymologically related either to the German word for “pale” (“bleich”) or “grinning” (“bleckend”), but is, in any case, a representation of Death as a skeleton. J. Mann, however, explains the remark as referring to a canon of Bruges, presumably of “rather skeletal appearance.” See Ysengrimus, ed. J. Mann, Leiden: E.J. Brill, 1987, ad loc. and note. If this is true, the relation between a “laughing/mocking Death” on the one hand and the reference to a “bony/skeletal person” on the other hand becomes rather tenuous. Moreover, even if, as J. Grimm asseverates, “dominus Blicero” is a personification of death, and even if, as Althof claims, the “laughing Death” of the Waltharius somehow uses the same imagery, it should be noted that in medieval iconography the personification of death as a skeletal figure does not occur until the thirteenth century – for which see L.E. Jordan, The iconography of death in western medieval art to 1350. Dissertation, Notre Dame University, Indiana, 1980, p. 97. |

It is also possible that “ridere” is here used in a different sense. “ridere” can be used with gods or personifications to mean “smile favorably,” as in Ovid, Tristia 1.5.27: “dum iuvat et vultu ridet Fortuna sereno” (“while Fortune aids and smiles with a peaceful countenance”) or Silius Italicus, Punica 5.227: “laeto Victoria vultu arridens” (“Victory, smiling with a cheerful expression”). “ridere” would then be used ironically in this context, meaning that when Death smiles upon you, it is anything but favorable. Cf. Statius, Thebaid 4.213: “grave Tisiphone risit gavisa futuris” (“Tisiphone smiled gravely, enjoying what was about to come”). The absence in the passages of the Waltharius of an adverbial accusative, however, rather strains the sense of “ridere,” if it is indeed to be taken in this way. | It is also possible that “ridere” is here used in a different sense. “ridere” can be used with gods or personifications to mean “smile favorably,” as in Ovid, Tristia 1.5.27: “dum iuvat et vultu ridet Fortuna sereno” (“while Fortune aids and smiles with a peaceful countenance”) or Silius Italicus, Punica 5.227: “laeto Victoria vultu arridens” (“Victory, smiling with a cheerful expression”). “ridere” would then be used ironically in this context, meaning that when Death smiles upon you, it is anything but favorable. Cf. Statius, Thebaid 4.213: “grave Tisiphone risit gavisa futuris” (“Tisiphone smiled gravely, enjoying what was about to come”). The absence in the passages of the Waltharius of an adverbial accusative, however, rather strains the sense of “ridere,” if it is indeed to be taken in this way. | ||

| − | It may be best to simply take “ridere” as “to mock” or “smile mockingly,” although | + | It may be best to simply take “ridere” as “to mock” or “smile mockingly,” although I have not found any parallels of such an act of personified Death in either classical or early medieval literature. It may therefore be necessary to take another look at “manes” and not equate it with “mors” so quickly. Although “manes” were generally considered to be good-natured spirits of the dead in antiquity (as opposed to “larvae” or “lemures”), they came to be equated with the evil ones, as Althof (1905 ad loc.) demonstrates by quoting a number of Old High German translations of “manes” by Notker. He then references J. Grimm, Deutsche Mythologie, Göttingen: Dieterichsche Buchhandlung, 1844, vol. 2, p. 789, where it is stated that in Nordic mythology, the dead who had not deserved to reach Walhalla were doomed to roam the earth, and often served as ghastly precursors to death. There is also a classical parallel where “manes” is used in a rather frightening context, see Horace, Odes 1.4: “palllida Mors aequo pulsat pede pauperum tabernas / regumque turris. o beate Sesti, / vitae summa brevis spem nos vetat incohare longam; / iam te premet nox fabulaeque Manes / et domus exilis Plutonia” (“pale Death knocks equally on the doors of poor taverns and the citadels of kings. O blessed Sestius, the short total of life prohibits us from beginning to have hope for longevity; soon night will press upon you and the shades of fable, and the insubstantial house of Pluto”). In the Waltharius, the “shades of fable” present themselves on the battlefield, smiling mockingly, to herald the impending death of Trogus. [JJTY] |

'''audaciter:''' The more common form is “audacter.” [JJTY]}} | '''audaciter:''' The more common form is “audacter.” [JJTY]}} | ||

| Line 590: | Line 590: | ||

|{{Commentary|''Secundum equiv. to iterum'' | |{{Commentary|''Secundum equiv. to iterum'' | ||

}} | }} | ||

| − | |{{Parallel|'' | + | |{{Parallel|''Aeneid'' 9.417: ''ecce aliud summa telum librabat ab aure. '' ‘He balances another weapon close to his ear.’ |

}} | }} | ||

|{{PicturesCont}} | |{{PicturesCont}} | ||

| − | |{{Meter|scansion=SSSDDS|elision | + | |{{Meter|scansion=SSSDDS|Note the two instances of elision in immediate succession, cum athleta and athleta ictum}} |

| | | | ||

|- | |- | ||

| Line 615: | Line 615: | ||

| | | | ||

| | | | ||

| − | |{{Parallel|''Aeneid'' 12.377: ''clipeo obiecto. . .'' ‘With his shield before him. . .’ '' | + | |{{Parallel|''Aeneid'' 12.377: ''clipeo obiecto. . .'' ‘With his shield before him. . .’ ''Aeneid'' 10.800: ''genitor nati parma protectus abiret.'' ‘The father, guarded by his son’s shield, could withdraw.’ |

}} | }} | ||

|{{PicturesCont}} | |{{PicturesCont}} | ||

| Line 682: | Line 682: | ||

| | | | ||

| | | | ||

| − | |{{Parallel|'' | + | |{{Parallel|''Aeneid'' 2.547-548.: ''referes ergo haec et nuntius ibis/ Pelidae genitori; illi mea tristia facta/ degeneremque Neoptolemum narrare memento;/ nunc morere.'' ‘Then you shall bear this news and go as messenger to my sire, Peleus’ son; be sure to tell him of my sorry deeds and his degenerate Neoptolemus! Now die!’ 10.600: ''morere et fratrem ne desere frater.'' ‘Die, and let not brother forsake brother!’ 10.743: ''nunc morere.'' ‘Now die.’ |

}} | }} | ||

|{{PicturesCont}} | |{{PicturesCont}} | ||

| Line 718: | Line 718: | ||

|{{Commentary|''Calcibus'': with'' ferientes'', describing their fall or perhaps their death throes''.'' | |{{Commentary|''Calcibus'': with'' ferientes'', describing their fall or perhaps their death throes''.'' | ||

}} | }} | ||

| − | |{{Parallel|'' | + | |{{Parallel|''Aeneid'' 10.404: ''caedit semianimis Rutulorum calcibus arva. '' ‘He spurns with his heels the Rutulian fields.’ 10.730-731.: ''calcibus atram/ tundit humum. '' ‘He hammers the black ground with his heels.’ |

}} | }} | ||

|{{PicturesCont}} | |{{PicturesCont}} | ||

Latest revision as of 11:42, 25 January 2010

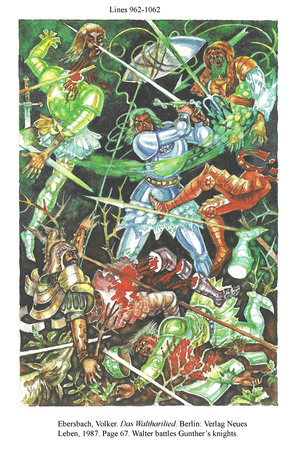

Walther is attacked by Eleuthir/Helmnot, assisted by Trogus, Tanastus, and Gunther; he slays all but Gunther (981–1061)

| Vix effatus haec truncavit colla precantis. | Aeneid 7.274: haec effatus. . . ‘With these words. . .’

|

SSSSDS | ||||

| At nonus pugnae Helmnod successit, et ipse | Aeneid 10.690: succedit pugnae. ‘He takes up the battle.’ 11.826: succedat pugnae. . . ‘That he should take my place in the battle. . .’

|

SSSSDS Hiatus: pugnae Helmnod |

Helmnod: see the note below on line 1008. JJTY | |||

| Insertum triplici gestabat fune tridentem, | SDSSDS | Insertum triplici gestabat fune tridentem: Perhaps a lance is meant here, as Althof (1905, ad loc.) claims: “eine schwere Lanze mit Widerhaken, wie sie die Franken führten.” A lance was one of the most common weapons used by Frankish soldiers (see Coupland 1990, pp. 46-48). [JJTY] | ||||

| Quem post terga quidem socii stantes tenuerunt, | Quem: the funis. The objective is to recover the trident after it has been thrown.

|

SDDSDS | ||||

| Consiliumque fuit, dum cuspis missa sederet | 985 | DDSSDS | ||||

| In clipeo, cuncti pariter traxisse studerent, | DSDSDS | |||||

| Ut vel sic hominem deiecissent furibundum; | Vel sic: “perhaps thus”

|

SDSSDS | ||||

| Atque sub hac certum sibi spe posuere triumphum. | Certum: predicative

|

DSDDDS | ||||

| Nec mora, dux totas fundens in brachia vires | DSSSDS | |||||

| Misit in adversum magna cum voce tridentem | 990 | Aeneid 3.68: magna. . .voce. . . ‘With loud voice. . .’

|

DSSSDS | |||

| Edicens: 'ferro tibi finis, calve, sub isto!' | Finis: sc. esto

|

Prudentius, Psychomachia 54: hic tibi finis erit. ‘This shall be thy last end.’

|

SSDSDS | |||

| Qui ventos penetrans iaculorum more coruscat, | Iaculorum more: the flying spear is not (pointlessly) compared to a iaculum (“javelin”), but rather to the iaculus, a flying tree-snake, as the poet explains in the next line.

|

SDDSDS | iaculorum: On flying tree snakes, see Pliny, Naturalis historia 8.14.36, and 8.35.85 for the iaculus in particular: “iaculum ex arborum ramis vibrari, nec pedibus tantum pavendas serpentes, sed ut missile volare tormento” (“...the iaculus balances on tree branches, nor need feet alone fear snakes, since it flies like a javelin from a sling”). This account may then have been used by Lucan in Bellum Civile 9.720 (“iaculique volucres,” “and flying iaculi”) and 9.823: “Ecce procul saevus sterilis se robore trunci / Torsit et immisit (iaculum vocat Africa) serpens / Perque caput Pauli transactaque tempora fugit” (“Lo! from afar a fierce serpent hurls itself with the strength of its trunk that has no appendages (Africa calls it the ‘iaculus’) and takes flight through Paulus’ head and pierces his temples”). [Ben Tipping's as yet unpublished 'Lucan's Cato' makes much of the imagery and symbolism of the snakes in book IX of the 'Pharsalia'. He suggests the "iaculus" along with the many other snakes assailing Cato's forces in the Libyan desert mock the Stoic sapiens, e.g. how the 'dispsas', whose name implies avarice, at 9.737-60 quite causes one of the soldiers to be consumed by such a burning thirst that he cuts his veins in order to drink his own blood. I bring it up because Gunther's avarice is what caused him to attack Walther in the first place, and the snakes, at least in Lucan, are symbolic of such un-Stoic (and un-Christian) greed. [AP]] This topic is expanded on by the fourth century writer Ammianus Marcellinus, who remarks in his Historiae (22.15.27) that Egypt has a rich variety of snakes, among which is mentioned the “acontia,” without adding any further description. Lucan’s account is used and quoted by Isidore in the Etymologiae sive Origines 12.29: “Iaculus serpens volans. De quo Lucanus: ‘Iaculique volucres.’ Exiliunt enim in arboribus, et dum aliquod animal obvium fuerit, iactant se super eum et perimunt; unde et iaculi dicti sunt” (“Iaculus the flying snake. About which Lucan says: ‘and the flying snakes.’ For they scale up trees, and when any animal comes on their path, they throw themselves on top of it and kill it; and that is why they are called javelins”). Isidore’s account also bears close resemblance to the fifth century account of Solinus, Collectanea rerum memorabilium 27.30: “iaculi arbores subeunt, e quibus vi maxima turbinati penetrant animal quodcumque obvium fortuna fecerit” (“iaculi go to trees, from which they hurl themselves with the greatest force and pierce any animal that fortune has set on their path”). See D’Angelo 1991, pp. 177-179 for an overview of the different opinions of scholars concerning the source used by the poet of the Waltharius. D’Angelo concludes that Lucan’s passage is echoed but not used as a source in this instance, and that Solinus is the more likely candidate for source material because “quod genus aspidis” (“which kind of snake” – it is difficult to know whether the poet of the Waltharius meant a snake in general by using “aspis” or the “asp” in particular) of line 993 in the Waltharius closely resembles Solinus 27.31: “Plures diuersaeque aspidum species” (“[there are] many and diverse kinds of asps”). However, when discussing asps, Isidore (12.13-14) mentions the following kinds (among others): “Dipsas, genus aspidis” (“Dipsas, a kind of asp”) and “Hypnalis, genus aspidis” (“Hypnalis, a kind of asp”). The passage from the Waltharius therefore sticks closer to Isidore by using the genitive singular of “aspis.”

Althof (1905, ad loc.) remarks: “Der Vergleich des Speeres mit einer Schlange ist echt germanisch.” Though this may be true, the very name attributed to this kind of serpent – iaculus, going back to the Greek ἀκοντίας (see Nicander, Theriaka 491), meaning “javelin” – evidences that this comparison was already made in Greco-Roman times. See also Aelianus, De natura animalium 6.18: “ἤδη δὲ καὶ ἀκοντίων δίκην ἑαυτόν τις μεθίησι καὶ ἐπιφέρεται, καὶ τό γε ὄνομα ἐξ οὗ δρᾷ ἔχει” (“Indeed a certain kind [i.e. of snake] launches itself and flies in the manner of javelins, and acquires its name from its action”). [JJTY] | |||

| Quod genus aspidis ex alta sese arbore tanto | DDDSDS | |||||

| Turbine demittit, quo cuncta obstantia vincat. | DSSSDS Elision: cuncta obstantia |

|||||

| Quid moror? umbonem sciderat peltaque resedit. | 995 | Umbonem: here in its more limited, literal sense. The shield is still intact.

|

Aeneid 4.325; 6.528: quid moror? ‘Why do I linger?’

|

DSDSDS | Quid moror? This phrase exposes the snake comparison for what it is: a poetic technique to heighten the tension in an exciting moment (Helmnod/Eleuthir has just thrown a lance towards Walther) by supplying unnecessary background information; the phrase “quid moror” (“why do I delay any longer?”) then signals the return to the action. [JJTY] Cf. line 92: "Sed quis plus remorer?" (But why stretch out my tale?), in which the poet accelerates the pace of the tale by eliding over the details of Walther's own surrender to Attila. [AP] | |

| Clamorem Franci tollunt saltusque resultat, | Aeneid 10.262: clamorem ad sidera tollunt. ‘They raise a shout to the sky.’ 11.622: clamorem tollunt. ‘They raise a shout.’ 8.305: consonat omne nemus strepitu collesque resultant. ‘The woodland rings with the clamour, and the hills resound.’

|

|

SSSSDS | saltusque resultat: The assonance of the “a” and the “u” gives an impression of an echo at the end of the line, reflecting the “echoing forest”. [JJTY] | ||

| Obnixique trahunt restim simul atque vicissim, | SDSDDS | restim ... vicissim: The rhyme here emphasizes the repetitive nature of the pulling. [JJTY] | ||||

| Nec dubitat princeps tali se aptare labori. | Princeps: Helmnod

|

Aeneid 10.588: aptat se pugnae. ‘He prepares for the fray.’

|

DSSSDS Elision: se aptare |

|||

| Manarunt cunctis sudoris flumina membris. | Aeneid 3.175: gelidus toto manabat corepore sudor. ‘A cold sweat bedewed all my limbs.’ 5.200: sudor fluit undique rivis. ‘Sweat streams down all their limbs.’

|

SSSSDS | Manarunt cunctis sudoris flumina membris: When all of Gunther’s men are straining with the effort to bring Walther down in this “rope pulling contest,” the action is briefly paused by an almost entirely spondaic meter as the camera slowly zooms in on the beads of sweat trickling down the men’s limbs. [JJTY] | |||

| Sed tamen haec inter velut aesculus astitit heros, | 1000 | Georgics 2.291-292: aesculus in primis, quae quantum vertice ad auras/ aetherias, tantum radice in Tartara tendit./ ergo non hiemes illam, non flabra neque imbres/ convellunt; immota manet. ‘Above all the great oak, which strikes its roots down towards the nether pit as far as it lifts its top to the airs of heaven. Hence no winter storms, no blasts or rains, uproot it; unmoved it abides.’ Aeneid 4.445-446.: ipsa haeret scopulis et quantum vertice ad auras/ aetherias, tantum radice in Tartara tendit:/ haud secus. . .heros/tunditur. ‘[The oak] clings to the crag, and as far as it lifts its top to the airs of heaven, so far it strikes its roots down towards hell: even so the hero is buffeted.’ 3.77: immotamque coli dedit et contemnere ventos. ‘He allows it to lie unmoved, defying the winds.’

|

DSDDDS | velut aesculus: The tree simile has become characteristic of epic: the present one goes back to Virgil, Aeneid 4.441-9 (which builds on Georgics, 2.291-2, though it is not a simile there), which has reminiscences of Catullus, 64.105-111 (the epyllion) and ultimately Homer, Iliad 12.131-136 and 16.765-771. Whereas the Homeric and Catullan similes, as well as the passage from the Georgics, center on an image of robust, physical strength, Virgil employs the simile in the Aeneid to portray Aeneas’ mental resolve in opposing Dido’s laments (delivered by Anna). See R.D. Williams, Virgil: Aeneid I-VI, London: Bristol Classical Press, 1972, ad loc.: “...he [Virgil, JJTY] has applied to mental strength what is generally an image of physical strength.” The poet of the Waltharius, in turn, flips the image around to portray Walther’s insurmountable strength in what is essentially a rope-pulling competition. As Althof (1905, ad loc.) rightly remarks, this passage is not evoking the mythical tree Yggdrasil from Germanic mythology. [JJTY] | ||

| Quae non plus petit astra comis quam Tartara fibris, | Fibris equiv. to radicibus

|

SDDSDS | ||||

| Contempnens omnes ventorum immota fragores. | SSSSDS Elision: ventorum immota |

|||||

| Certabant hostes hortabanturque viritim, | SSSSDS | |||||

| Ut, si non quirent ipsum detrudere ad arvum, | Detrudere ad arvum: i.e., kill?

|

SSSSDS Elision: detrudere ad |

||||

| Munimen clipei saltem extorquere studerent, | 1005 | Aeneid 12.357: dextrae mucronem extorquet. ‘He wrests the sword from his hand.’

|

SDSSDS Elision: saltem extorquere |

|||

| Quo dempto vivus facile caperetur ab ipsis. | Facile: the e of the adverb is here long.

|

SSDDDS | ||||

| Nomina quae restant edicam iamque trahentum: | DSSSDS | 1007-1011: Again the poet increases the tension by providing a catalog of the participants and their place of origin, right in the middle of the action. [JJTY] | ||||

| Nonus Eleuthir erat, Helmnod cognomine dictus, | Eleuthir…Helmnod: a double name, cf. line 687.

|

Aeneid 3.702: Gela fluvii cognomine dicta. . . ‘Gela, named after its river. . .’

|

DDSSDS | Nonus Eleuthir erat, Helmnod cognomine dictus: According to Schröder (1931, pp. 150-151), Eleuthir is a possible Langobardic double version of the name (Eleuthir vs. Leuthir). It is a Hellenized version of (He)leuthere/Liuthere, analogous to the Greek ἐλεύθερος (“free”), resulting in a word-play with "Frank," which also means "free." Schröder (ibid.) also remarks that one would expect Eleuthir to be the nickname, not Helmnod. Helmnod, according to Wagner (1992, pp. 119-120), is a composite name meaning “helmet-blow,” from the Old High German (h)nod. It is possible that the mention of two names of the same person reflects different (oral) traditions of the Waltharius. [JJTY] | ||

| Argentina quidem decimum dant oppida Trogum, | Argentina…oppida: the Roman town Argentoratum, today Strasbourg, France.

|

|

SDDSDS | |||

| Extulit undecimum pollens urbs Spira Tanastum, | 1010 | Spira: Speyer, now a city in the German Rhineland-Palatinate.

|

DDSSDS | |||

| Absque Haganone locum rex supplevit duodenum. | Gunther takes the place of Hagen, originally reckoned among the twelve (cf. lines 475-477).

|

DDSSDS Elision: absque Haganone |

||||

| Quattuor hi adversum summis conatibus unum | DSSSDS Elision: hi adversum |

Quattuor ... unum: Notice how the poet nicely emphasizes the efforts of many against one by framing the verse. [JJTY] | ||||

| Contendunt pariter multo varioque tumultu. | Aeneid 2.122: magno. . .tumultu. . . ‘With loud clamour. . .’

|

SDSDDS | ||||

| Interea Alpharidi vanus labor incutit iram, | Aeneid 11.728: incutit iras. ‘He fills him with wrath.’

|

DDSDDS Elision: interea Alpharidi |

||||

| Et qui iam pridem nudarat casside frontem, | 1015 | SSSSDS | iam pridem nudarat casside frontem: See 959-961: “Vir tamen illustris dum cunctari videt illos, / Vertice distractas suspendit in arbore cristas / Et ventum captans sudorem tersit anhelus” (“The famous man, when he saw they were hesitating, / Took his plumed helmet off and hung it on a tree, / Then caught his breath and, gasping, wiped away the sweat”). As line 969 tells us, Walther had not had the opportunity to put his helmet back on when Randolf rushed upon him (“Nec tamen et galeam fuerat sumpsisse facultas,” “However, Walter had no chance to don his helmet.”). [JJTY] | |||

| In framea tunicaque simul confisus aena | Framea equiv. to gladio here, though cf. Tac. Germ 6: hastas vel ipsorum vocabulo frameas gerunt.

|

DDDSDS | ||||

| Omisit parmam primumque invasit Eleuthrin. | SSSSDS Elision: primumque in |

|||||

| Huic galeam findens cerebrum diffudit et ipsam | DSDSDS | |||||

| Cervicem resecans pectus patefecit, at aegrum | Aeneid 10.601: latebras animae pectus mucrone recludit. ‘With the sword he cleft open his breast, where life lies hidden.’

|

SDSDDS | ||||

| Cor pulsans animam liquit mox atque calorem. | 1020 | Aeneid 3.140: linquebant dulcis animas. ‘Men gave up their sweet lives.’ 9.475: miserae calor ossa reliquit. ‘Warmth left her hapless frame.’

|

SDSSDS | |||

| Inde petit Trogum haerentem in fune nefando. | DSSSDS Elision: haerentem in Hiatus: Trogum haerentem |

haerentem in fune: D’Angelo (1991, p. 171) quotes as a parallel to this passage Lucan, Bellum Civile 5.514 (“Rupibus exesis haerentem fune carinam,” “a ship hanging on to a rope in a hewn cave”) and 3.628 (“Haesissem, quamvis amens, in fune retentus,” “I would have hung on, although I was out of my mind, hanging onto the rope”). [JJTY] | ||||

| Qui subito attonitus recidentis morte sodalis | Aeneid 10.386: furit incautum crudeli morte sodalis. ‘He rages, reckless over his comrade’s cruel death.’ 11.796: sterneret ut subita turbatam morte Camillam. . . ‘That he might overthrow and strike down Camilla in sudden death.’

|

DDDSDS Elision: subito attonitus |

||||

| Horribilique hostis conspectu coeperat acrem | Aeneid 11.271: horribili visu portenta sequuntur. ‘Portents of dreadful view pursue me.’

|

DSSSDS Elision: horribilique hostis |

||||

| Nequiquam temptare fugam voluitque relicta | Georgics 3.141-142.: acri/ carpere prata fuga. . . ‘To scour the meadows in swift flight. . .’

|

SSDDDS | ||||

| Arma recolligere, ut rursum repararet agonem. | 1025 | Aeneid 5.15: colligere arma iubet. ‘He bids them gather in the tackling.’

|

DDSDDS Elision: recolligere ut |

reparare agonem: Like the “athleta” in 962, the poet elects to use a word that bears a distinctly Christian connotation. Though it was used in Latin in a literal and secular context to denote “match” or “contest,” it was already used in the Bible (and retained as a Greek word in the Latin translations) as a metaphor of a moral struggle. So 1 Cor 9:25: “omnis autem qui in agone contendit ab omnibus se abstinet et illi quidem ut corruptibilem coronam accipiant nos autem incorruptam” (“Everyone who competes in the games goes into strict training. They do it to get a crown that will not last; but we do it to get a crown that will last forever.”). It was not long before “agon” also came to be used of the fight that martyrs fought (highly appropriate, as they often met their ends in the arena), see for instance the Acts of Perpetua and Felicitas (I, 9.4): “Reuocatus et Felicitas a leopardis gloriosum agonem impleuerunt” (“Revocatus and Felicitas finished their glorious struggle through leopards”). Thence “agon” was also used of the Christian’s moral struggle in general – see e.g. Lactantius, Epitome divinarum institutionum 24.11: “summa igitur prudentia deus materiam uirtutis in malis posuit: quae idcirco fecit, ut nobis constitueret agonem, in quo uictores inmortalitatis praemio coronaret” (“Therefore God prudently placed the opportunity of virtue in vices; and he created vices, so that he might give us a contest, in which he might crown the victors with the reward of immortality”).

What is the significance of the usage of both “athleta” and “agon” in such close proximity – words that have such obvious Christian connotations, but are used in an otherwise “secular” description of battle scenes? This is an interesting problem because “athleta” is used for three parties: first it is used for Randolf, one of Gunther’s men; then it is used for Walther; finally it is used by Walther to describe Hagan. This means, presumably, that all three are Christians, fighting the battle – not just of the Vosges, but also of life. Each, in their own way, is fighting their battle against sin: Randolf against avarice in his lust for treasure (either that or, incited as he has been by Gunther to exact revenge, against anger), Walther against arrogance (see the boasting episode in 561-565), Hagan against the anger he has conceived over Gunther’s insulting remarks (632: “tunc heros magnam iuste conceperat iram, / si tamen in dominum licitum est irascier ullum,” “The hero rightly then became extremely angered, / If to be angry with one’s lord is ever right.”). Thus each is involved in a moral struggle so that they too, when their time has come, may say with Cyprian (Ad Quirinum 3.16): “Bonum agonem certavi, cursum perfeci, fidem servavi” (“I have fought a good fight, I have finished the race, I have kept the faith”). [JJTY] | ||

| Nam cuncti funem tracturi deposuerunt | Aeneid 12.707: armaque deposuere umeris. ‘They took off the armour from their shoulders.’

|

SSSSDS | ||||

| Hastas cum clipeis.) sed quanto maximus heros | Aeneid 12.707: armaque deposuere umeris. ‘They took off the armour from their shoulders.’

|

SDSSDS | ||||

| Fortior extiterat, tanto fuit ocior, olli | Olli…capto: Trogus, dative of disadvantage. For the construction with the ablative cursu, cf. line 1325: furto captum.

|

DDSDDS | ||||

| Et cursu capto suras mucrone recidit | SSSSDS | 1029-1030: Notice how, in contrast to the previous quick-paced verse (which describes the speed of Walther), the almost entirely spondaic meters of both vs. 1029 and 1030 strikingly represent the slowed-down action as Walther, having caught up to one of the men, manages to slow Trogus down by cutting his hamstring. [JJTY] | ||||

| Ac sic tardatum praevenit et abstulit eius | 1030 | SSSDDS | ||||

| Scutum. sed Trogus, quamvis de vulnere lassus, | De vulnere: cf. note on prologue, line 10.

|

SSSSDS | scutum: The enjambment (continuation of a syntactical unit over into the following verse) causes the shield to be effectively “snatched” from the previous verse, corresponding with “abstulit” (“stole”) in 1030. [JJTY] | |||

| Mente tamen fervens saxum circumspicit ingens, | Aeneid 12.896-897.: saxum circumspicit ingens. . .ille manu raptum trepida torquebat in hostem. ‘He glances round and sees a huge stone. . .With hurried grasp, he seized and hurled it at his foe.’ 12.266: adversos telum contorsit in hostes. ‘Darting forward, he hurled his spear full against the foe.’

|

DSSSDS | ||||

| Quod rapiens subito obnixum contorsit in hostem | DDSSDS Elision: subito obnixum |

|||||

| Et proprium a summo clipeum fidit usque deorsum. | Proprium…scutum: Trogus’s own shield, being used by Waltharius.

|

DSDDDS Elision: proprium a |

||||

| Sed retinet fractum pellis superaddita lignum. | 1035 | DSSDDS | sed retinet fractum pellis superaddita lignum: This is consistent with the structure of shields in the Carolingian period, see Coupland 1990, pp. 35-38. Cf. 776: “taurino contextum tergore lignum” (“the bull’s-hide-covered wood”). [JJTY] | |||

| Moxque genu posito viridem vacuaverat aedem | Viridem…aedem equiv. to vaginam Vacuaverat: the subject is Trogus.

|

DDDDDS | vacuaverat aedem: I.e.: he unsheathed his sword. A prime example of the kenning or circumlocution typical of Germanic literature. [JJTY] | |||

| Atque ardens animis vibratu terruit auras, | Prudentius, Psychomachia 297: territat auras. ‘He affrighted the heavens.’

|

SDSSDS Elision: atque ardens |

||||

| Et si non quivit virtutem ostendere factis, | SSSSDS Elision: virtutem ostendere |

virtutem ... virilem: Note the word play on “virtutem” and “virilem.” The same word play occurs in the context of martyrdom in Acts of Perpetua and Felicitas II.9.2: “Praecedentibus uero sanctis martyribus Felicitas sequebatur, quae desiderio Christi et amore martyrii nec obstetricem quaesiuit, nec partus sensit iniuriam, sed uere felix et suo sanguine consecranda, non solum femineo sexui, sed etiam uirili uirtuti praebebat exemplum, post onus uteri coronam martyrii perceptura” (“After the saintly martyrs had preceded her, Felicitas followed, who sought neither an obstetrician because of her desire for Christ and her love for martyrdom, nor did she feel injustice for her child, but offered, truly happy and about to be consecrated with her own blood, an example not only to the feminine sex, but also to manly courage – she, who would receive the crown of martyrdom after the burden of her womb”). Cf. Paulinus of Nola, Carmina 26.159: “femineas quoque personas uirtute uirili / induit alma fides” (“kind faith also clothes female persons in manly courage”). [JJTY] | ||||

| Corde tamen habitum patefecit et ore virilem. | Habitum equiv. to animum

|

Aeneid 9.311: ante annos animumque gerens curamque virilem. . . ‘With a man’s mind and a spirit beyond his years. . .’

|

DDDDDS | |||

| Nec manes ridere videns audaciter infit: | 1040 | Manes ridere: the parallel image in line 849 suggests that ridere depends not on infit (so Wieland) but rather on videns.

|

SSDSDS | Nec manes ridere videns: This is a puzzling phrase. Is it possible that “manes” is metonymically used for “death” and is here used with “ridere” to personify death? This would seem likely, because of the similar phrase in Hagan’s speech in 849-850: “Aspice mortem, / Qualiter arridet!” (“Look at Death, / How it is grinning!”); see also 1327: “Quem quoque continuo esurienti porgeret Orco” (“Him too he would have sent straightway to hungry Orcus”). Althof (1905, ad loc.) compares this passage to “Dominus Blitero” in the Ysengrimus / Reinardus Vulpes (5.1100): “Hanc tibi dono gigam, pagana est utpote porrum / Osseaque ut dominus Blitero, sume, vide!” (“I give you this fiddle, as common as a leek / and as bony as lord Blitero – see, take it!”). According to J. Grimm, Deutsche Mythologie, Göttingen: Dieterichsche Buchhandlung, 1844, vol. 2, pp. 849-850, the name “Blitero” could be etymologically related either to the German word for “pale” (“bleich”) or “grinning” (“bleckend”), but is, in any case, a representation of Death as a skeleton. J. Mann, however, explains the remark as referring to a canon of Bruges, presumably of “rather skeletal appearance.” See Ysengrimus, ed. J. Mann, Leiden: E.J. Brill, 1987, ad loc. and note. If this is true, the relation between a “laughing/mocking Death” on the one hand and the reference to a “bony/skeletal person” on the other hand becomes rather tenuous. Moreover, even if, as J. Grimm asseverates, “dominus Blicero” is a personification of death, and even if, as Althof claims, the “laughing Death” of the Waltharius somehow uses the same imagery, it should be noted that in medieval iconography the personification of death as a skeletal figure does not occur until the thirteenth century – for which see L.E. Jordan, The iconography of death in western medieval art to 1350. Dissertation, Notre Dame University, Indiana, 1980, p. 97.

It is also possible that “ridere” is here used in a different sense. “ridere” can be used with gods or personifications to mean “smile favorably,” as in Ovid, Tristia 1.5.27: “dum iuvat et vultu ridet Fortuna sereno” (“while Fortune aids and smiles with a peaceful countenance”) or Silius Italicus, Punica 5.227: “laeto Victoria vultu arridens” (“Victory, smiling with a cheerful expression”). “ridere” would then be used ironically in this context, meaning that when Death smiles upon you, it is anything but favorable. Cf. Statius, Thebaid 4.213: “grave Tisiphone risit gavisa futuris” (“Tisiphone smiled gravely, enjoying what was about to come”). The absence in the passages of the Waltharius of an adverbial accusative, however, rather strains the sense of “ridere,” if it is indeed to be taken in this way. It may be best to simply take “ridere” as “to mock” or “smile mockingly,” although I have not found any parallels of such an act of personified Death in either classical or early medieval literature. It may therefore be necessary to take another look at “manes” and not equate it with “mors” so quickly. Although “manes” were generally considered to be good-natured spirits of the dead in antiquity (as opposed to “larvae” or “lemures”), they came to be equated with the evil ones, as Althof (1905 ad loc.) demonstrates by quoting a number of Old High German translations of “manes” by Notker. He then references J. Grimm, Deutsche Mythologie, Göttingen: Dieterichsche Buchhandlung, 1844, vol. 2, p. 789, where it is stated that in Nordic mythology, the dead who had not deserved to reach Walhalla were doomed to roam the earth, and often served as ghastly precursors to death. There is also a classical parallel where “manes” is used in a rather frightening context, see Horace, Odes 1.4: “palllida Mors aequo pulsat pede pauperum tabernas / regumque turris. o beate Sesti, / vitae summa brevis spem nos vetat incohare longam; / iam te premet nox fabulaeque Manes / et domus exilis Plutonia” (“pale Death knocks equally on the doors of poor taverns and the citadels of kings. O blessed Sestius, the short total of life prohibits us from beginning to have hope for longevity; soon night will press upon you and the shades of fable, and the insubstantial house of Pluto”). In the Waltharius, the “shades of fable” present themselves on the battlefield, smiling mockingly, to herald the impending death of Trogus. [JJTY] audaciter: The more common form is “audacter.” [JJTY] | ||

| O mihi si clipeus vel sic modo adesset amicus! | DDSDDS Elision: modo adesset |

|||||

| Fors tibi victoriam de me, non inclita virtus | DDSSDS | |||||

| Contulit. ad scutum mucronem hic tollito nostrum!' | DSSSDS Elision: mucronem hic |

|||||

| Tum quoque subridens 'venio iam' dixerat heros | DSDSDS | |||||

| Et cursu advolitans dextram ferientis ademit. | 1045 | SDSDDS Elision: cursu advolitans |

||||

| Sed cum athleta ictum libraret ab aure secundum | Secundum equiv. to iterum

|

Aeneid 9.417: ecce aliud summa telum librabat ab aure. ‘He balances another weapon close to his ear.’

|

SSSDDS | |||

| Pergentique animae valvas aperire studeret, | SDSDDS Elision: pergentique animae |

|||||

| Ecce Tanastus adest telis cum rege resumptis | DDSSDS | |||||

| Et socium obiecta protexit vulnere pelta. | Aeneid 12.377: clipeo obiecto. . . ‘With his shield before him. . .’ Aeneid 10.800: genitor nati parma protectus abiret. ‘The father, guarded by his son’s shield, could withdraw.’

|

DSSSDS Elision: socium obiecta |

||||

| Hinc indignatus iram convertit in ipsum | 1050 | SSSSDS | ||||

| Waltharius humerumque eius de cardine vellit | Aeneid 2.480: postisque a cardine vellit. ‘From their hinge he tears the doors.’

|

DDSSDS Elision: humerumque eius |

||||

| Perque latus ducto suffudit viscera ferro. | DSSSDS | |||||

| Ave! procumbens submurmurat ore Tanastus. | SSSDDS | |||||

| Quo recidente preces contempsit promere Trogus | DDSSDS | |||||

| Conviciisque sui victorem incendit amaris, | 1055 | Aeneid 10.368: dictis virtutem accendit amaris. ‘With bitter words he fires their courage.’

|

DDSSDS Elision: victorem incendit |

|||

| Seu virtute animi, seu desperaverat. exin | SDSSDS Elision: virtute animi |

|||||

| Alpharides: 'morere' inquit 'et haec sub Tartara transfer | Aeneid 2.547-548.: referes ergo haec et nuntius ibis/ Pelidae genitori; illi mea tristia facta/ degeneremque Neoptolemum narrare memento;/ nunc morere. ‘Then you shall bear this news and go as messenger to my sire, Peleus’ son; be sure to tell him of my sorry deeds and his degenerate Neoptolemus! Now die!’ 10.600: morere et fratrem ne desere frater. ‘Die, and let not brother forsake brother!’ 10.743: nunc morere. ‘Now die.’

|

DDDSDS Elision: morere inquit |

||||

| Enarrans sociis, quod tu sis ultus eosdem.' | SDSSDS | |||||

| His dictis torquem collo circumdedit aureum. | Variously interpreted. (1) Waltharius strangles Trogus with a gold necklace that Trogus is wearing. (2) The torquem aureum is actually one of blood, yielding a figurative description of decapitation. (3) The neck in question is Waltharius’s, and the torques is a trophy of his victory, either literally (taken from Trogus) or figuratively (referring to a Roman practice, cf. Statius Thebaid 10.517, Silius Italicus Punica 15.255).

|

Danihel Propheta 5.29: circumdata est torques aurea collo eius. ‘A chain of gold was put around his neck.’ Liber Genesis 41.42: collo torquem auream circumposuit. ‘He put a chain of gold about his neck.’

|

SSSSDS False quantities: aureum |

|||

| Ecce simul caesi volvuntur pulvere amici, | 1060 | DSSSDS Elision: pulvere amici |

||||

| Crebris foedatum ferientes calcibus arvum. | Calcibus: with ferientes, describing their fall or perhaps their death throes.

|

Aeneid 10.404: caedit semianimis Rutulorum calcibus arva. ‘He spurns with his heels the Rutulian fields.’ 10.730-731.: calcibus atram/ tundit humum. ‘He hammers the black ground with his heels.’

|

SSDSDS |