Difference between revisions of "Waltharius419"

(→Flight of Walther and Hildegund to the area of Worms (419–435)) |

Ana Enriquez (talk | contribs) (→Flight of Walther and Hildegund to the area of Worms (419–435)) |

||

| (12 intermediate revisions by 3 users not shown) | |||

| Line 24: | Line 24: | ||

| | | | ||

|{{Meter|scansion=SSDDDS|elision=arte accersitas}} | |{{Meter|scansion=SSDDDS|elision=arte accersitas}} | ||

| − | | | + | | {{Comment|Walther may seem remarkably well-versed in wilderness survival techniques, knowing two forms of catching birds and fishing. Later medieval heroes, such as the knights of romance, rely more heavily on hospitality at strange castles, and even when readers are told that a knight has spent months in the wilderness, his hunting and fishing techniques are rarely narrated. By contrast, tales of the Norse gods and heroes do depict hunting and fishing. Thor demonstrates his prowess as a fisherman against the world-serpent itself, while Loki and Odin catch and kill and otter for sport, with disastrous consequences. This contrast emphasizes the changing nature of medieval society. By the time of the French and German romances, the Frankish homeland was largely "tamed," made arable and brought under the rule of castles, manors, or towns. Walther seems to be walking instead through a truly wild land, and his heroism relies in part on his ability to draw sustenance from that land. MCD.}} |

|- | |- | ||

|[[Nunc]] [[fallens]] [[visco]], [[nunc]] [[fisso]] [[denique]] [[ligno]]. | |[[Nunc]] [[fallens]] [[visco]], [[nunc]] [[fisso]] [[denique]] [[ligno]]. | ||

| Line 43: | Line 43: | ||

| | | | ||

|{{Meter|scansion=DSSDDS}} | |{{Meter|scansion=DSSDDS}} | ||

| − | | {{Comment|"flumina...curva": most likely, tributaries of the Rhine and Danube, though at times the geography of the poem seems less literal than topical. In the course of the poem, we see mountains, battle-fields, river-areas, and even a brief glimpse of the ocean, where the Huns empire supposedly reaches, though in reality, Hunnish hordes never reached the Atlantic. The poem's journeys throughout Europe render it a form of "world tour," so the diverse settings are appropriate. MCD}} | + | | {{Comment|"flumina...curva": most likely, tributaries of the Rhine and Danube, though at times the geography of the poem seems less literal than topical. In the course of the poem, we see mountains, battle-fields, river-areas, and even a brief glimpse of the ocean, where the Huns' empire supposedly reaches, though in reality, Hunnish hordes never reached the Atlantic. The poem's journeys throughout Europe render it a form of "world tour," so the diverse settings are appropriate. MCD}} |

|- | |- | ||

|[[Immittens]] [[hamum]] [[rapuit]] [[sub]] [[gurgite]] [[praedam]]. | |[[Immittens]] [[hamum]] [[rapuit]] [[sub]] [[gurgite]] [[praedam]]. | ||

| Line 60: | Line 60: | ||

| | | | ||

|{{Meter|scansion=DSDDDS}} | |{{Meter|scansion=DSDDDS}} | ||

| − | | {{Comment | + | | {{Comment|"famis pestem": an unusual use of "pestem" (pestis, pestis, feminine) which usually refers to a literal plague or disease. In classical Latin, "pestis" can be used metonymically to signify "death," which is probably what the Waltharius-poet intends here, as in "death by hunger." However, the specific phrase is without precedent. MCD [Take a look at Abbo of St. Germain, De bello Parisiaco 1, ed. Migne, PL 132.727B.]}} |

|- | |- | ||

|[[Namque]] [[fugae]] [[toto]] [[se1|se]] [[tempore]] [[virginis]] [[usu]] | |[[Namque]] [[fugae]] [[toto]] [[se1|se]] [[tempore]] [[virginis]] [[usu]] | ||

| Line 77: | Line 77: | ||

| | | | ||

|{{Meter|scansion=DSDSDS}} | |{{Meter|scansion=DSDSDS}} | ||

| − | | {{Comment|Ward makes much of Walther’s | + | | {{Comment|Ward makes much of Walther’s abstention from sex with Hildegund in the wilderness. Instead of treating her as spoils of war, he shows respect for her noble status and her potential to become a wife and mother of heirs. Such heirs would need to be incontestable, not sullied by the shadow of extramarital sex. Hence, the poet repeatedly uses the word "virgo" to describe Hildegund (for example, at lines 110, 235, 248, and 287). Though the term “chivalry” is anachronistic in this context, Walther’s careful respect for Hildegund as a marriageable woman (and thus, a stabilizer of culture) and his avoidance of the sin of lust make him a prototype for the later “domesticated” heroes of romance. For Ward, the poem represents the efforts of the Carolingian church to craft just such religious and domestic values. MCD |

| + | |||

| + | Perhaps Walther's abstinence is also connected with the other associations with Lent? [JJTY]}} | ||

|- | |- | ||

|[[Ecce]] [[quater]] [[denos]] [[sol]] [[circumflexerat]] [[orbes]], | |[[Ecce]] [[quater]] [[denos]] [[sol]] [[circumflexerat]] [[orbes]], | ||

| Line 83: | Line 85: | ||

|{{Commentary|''Quater denos'': the length of time is perhaps of biblical inspiration. | |{{Commentary|''Quater denos'': the length of time is perhaps of biblical inspiration. | ||

}} | }} | ||

| − | |{{Parallel|'' | + | |{{Parallel|''Aeneid'' 5.131: ''circumflectere cursus. . .'' ‘To double round the courses. . .’ |

}} | }} | ||

| | | | ||

|{{Meter|scansion=DSSSDS}} | |{{Meter|scansion=DSSSDS}} | ||

| − | | {{Comment|Walther and Hildegund wander in the wilderness between the land of the Huns and the territory of Worms for forty days, a period which echoes the wandering of the Jews prior to their entrance into the Promised Land (cf. Exodus, Leviticus, Numbers, Deuteronomy), the period of Christ’s temptation in the desert (cf. Matthew 4:1-11; Mark 1:13-14; Luke 4:1-15), and the length of Lent. The specification of forty days is no accident, but as usual in the poem, the function of such a religious reference is unclear. | + | | {{Comment|Walther and Hildegund wander in the wilderness between the land of the Huns and the territory of Worms for forty days, a period which echoes the wandering of the Jews prior to their entrance into the Promised Land (cf. Exodus, Leviticus, Numbers, Deuteronomy), the number of days and nights that Moses spends on the mountaintop (cf. Exodus 24:18), the period of Christ’s temptation in the desert (cf. Matthew 4:1-11; Mark 1:13-14; Luke 4:1-15), and the length of Lent. The specification of forty days is no accident, but as usual in the poem, the function of such a religious reference is unclear. |

It may imply a spiritual significance to Walter’s ordeal, fulfilled in the “justice” meted out by the poem’s peculiar ending. Similarly, if Walter and Hildegund’s journey functions as a kind of Lent, then Walther’s bloody battle might constitute an analogue to Good Friday or other older and more indigenous tales of human sacrifice and rebirth. Indeed, after passing through the carnage and loss of Walther’s single combat, order, friendship, and loyalty are reborn and restored in a kind of resurrection. | It may imply a spiritual significance to Walter’s ordeal, fulfilled in the “justice” meted out by the poem’s peculiar ending. Similarly, if Walter and Hildegund’s journey functions as a kind of Lent, then Walther’s bloody battle might constitute an analogue to Good Friday or other older and more indigenous tales of human sacrifice and rebirth. Indeed, after passing through the carnage and loss of Walther’s single combat, order, friendship, and loyalty are reborn and restored in a kind of resurrection. | ||

The time specification may also emphasize that the Waltharius is a tale preliminary to Walter’s illustrious rule, much as the wanderings of Christ or the Israelites in the desert forms a prelude to a well-known, public career. | The time specification may also emphasize that the Waltharius is a tale preliminary to Walter’s illustrious rule, much as the wanderings of Christ or the Israelites in the desert forms a prelude to a well-known, public career. | ||

| − | Alternatively, the specification of forty days may simply function as yet another religious | + | Alternatively, the specification of forty days may simply function as yet another vague and attenuated religious reference in the poem, like the references to fauns (ll. 761-763) or Wieland (ll. 965-966). Though Christianity can be assumed to be a more "living" religion to the Waltharius-poet, the references to Christian belief through the poem are almost as enigmatic as the references to Germanic or Roman practice. Christianity has a similarly ambiguous status in Beowulf, so this might be a common feature of Germanic poetry written relatively soon after the introduction of Christianity. MCD}} |

|- | |- | ||

|[[Ex]] [[quo1|quo]] [[Pannonica]] [[fuerat]] [[digressus]] [[ab]] [[urbe]]. | |[[Ex]] [[quo1|quo]] [[Pannonica]] [[fuerat]] [[digressus]] [[ab]] [[urbe]]. | ||

| Line 139: | Line 141: | ||

</gallery>}} | </gallery>}} | ||

|{{Meter|scansion=DDSSDS}} | |{{Meter|scansion=DDSSDS}} | ||

| − | | | + | | {{Comment|Worms has existed at least since the time of Julius Caesar. In the fifth century, it became the Burgundian capital, not the Frankish seat, though it remained an important state center when the Franks came to occupy the Rhineland in later centuries. It features in another German epic, the 12th-century Nibelungenlied, when Gunther and Hagan appear again, this time as Burgundians. The Nibelungenlied, though written during the High Middle Ages, would seem to have roots in earlier myth, like the Waltharius, since versions of the story appear in Scandinavian fragments. Indeed, some echoes of the story might be present in the poem itself. Grimm suggested that line 555's "Franci nebulones" might be corrected as "Franci nivilones," though this theory has not met with great favor (see note to line 555).}} |

|- | |- | ||

|[[Illic]] [[pro]] [[naulo]] [[pisces]] [[dedit]] [[antea]] [[captos]] | |[[Illic]] [[pro]] [[naulo]] [[pisces]] [[dedit]] [[antea]] [[captos]] | ||

| Line 149: | Line 151: | ||

| | | | ||

|{{Meter|scansion=SSSDDS}} | |{{Meter|scansion=SSSDDS}} | ||

| − | | | + | |{{Comment|Parkes suggests that avarice motivates Walther to pay with fish instead of treasure, and that this is contrasted with the generosity of the ferry-man, who gives the fish to Gunther (460). [AE]}} |

|- | |- | ||

|[[Et]] [[mox]] [[transpositus]] [[graditur]] [[properanter]] [[anhelus]]. | |[[Et]] [[mox]] [[transpositus]] [[graditur]] [[properanter]] [[anhelus]]. | ||

| Line 157: | Line 159: | ||

| | | | ||

|{{Meter|scansion=SDDDDS}} | |{{Meter|scansion=SDDDDS}} | ||

| − | | | + | | {{Comment|The heavily dactylic line imitates the swift movement of Walther and Hildegund's journey. MCD}} |

|- | |- | ||

|} | |} | ||

Latest revision as of 23:50, 15 December 2009

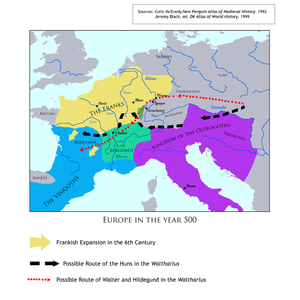

Flight of Walther and Hildegund to the area of Worms (419–435)

| Waltharius fugiens, ut dixi, noctibus ivit, | DDSSDS | |||||

| Atque die saltus arbustaque densa requirens | 420 | DSSDDS | ||||

| Arte accersitas pariter capit arte volucres, | SSDDDS Elision: arte accersitas |

Walther may seem remarkably well-versed in wilderness survival techniques, knowing two forms of catching birds and fishing. Later medieval heroes, such as the knights of romance, rely more heavily on hospitality at strange castles, and even when readers are told that a knight has spent months in the wilderness, his hunting and fishing techniques are rarely narrated. By contrast, tales of the Norse gods and heroes do depict hunting and fishing. Thor demonstrates his prowess as a fisherman against the world-serpent itself, while Loki and Odin catch and kill and otter for sport, with disastrous consequences. This contrast emphasizes the changing nature of medieval society. By the time of the French and German romances, the Frankish homeland was largely "tamed," made arable and brought under the rule of castles, manors, or towns. Walther seems to be walking instead through a truly wild land, and his heroism relies in part on his ability to draw sustenance from that land. MCD. | ||||

| Nunc fallens visco, nunc fisso denique ligno. | Fisso…ligno: a kind of trap for birds, consisting of a piece of green wood split down the middle with the two halves held apart at one end, such that when a bird arrives, attracted by bait scattered in the middle, the two halves will snap together and break its legs.

|

Georgics 1.139-140.: tum laqueis captare feras et fallere visco/ inventum. ‘Then was discovered how to catch game with traps and to snare birds with lime.’ Aeineid 9.413-414.: hasta. . .fisso transit praecordia ligno. ‘The spear pierces the midriff with the broken wood.’

|

SSSSDS | |||

| Ast ubi pervenit, qua flumina curva fluebant, | Georgics 2.11-12.: camposque et flumina late/ curva tenent. ‘Far and wide they claim the plains and winding rivers.’

|

DSSDDS | "flumina...curva": most likely, tributaries of the Rhine and Danube, though at times the geography of the poem seems less literal than topical. In the course of the poem, we see mountains, battle-fields, river-areas, and even a brief glimpse of the ocean, where the Huns' empire supposedly reaches, though in reality, Hunnish hordes never reached the Atlantic. The poem's journeys throughout Europe render it a form of "world tour," so the diverse settings are appropriate. MCD | |||

| Immittens hamum rapuit sub gurgite praedam. | Georgics 4.395: sub gurgite. . . ‘Beneath the wave. . .’

|

SSDSDS | ||||

| Atque famis pestem pepulit tolerando laborem. | 425 | DSDDDS | "famis pestem": an unusual use of "pestem" (pestis, pestis, feminine) which usually refers to a literal plague or disease. In classical Latin, "pestis" can be used metonymically to signify "death," which is probably what the Waltharius-poet intends here, as in "death by hunger." However, the specific phrase is without precedent. MCD [Take a look at Abbo of St. Germain, De bello Parisiaco 1, ed. Migne, PL 132.727B.] | |||

| Namque fugae toto se tempore virginis usu | Virginis usu: The poet praises Waltharius for abstaining from sexual intercourse.

|

DSSDDS | Walther refrains from "use" of Hildegund, which suggests that she carries a different status from the rest of the treasure. As earlier, the poet takes pains to depict a companionate relationship between the two exiles, emphasizing Hildegund's personal, feminine value above mere chattel. See John O. Ward, "After Rome: Medieval Epic," in Roman Epic, ed. A.J. Boyle (Routledge, 1993). MCD | |||

| Continuit vir Waltharius laudabilis heros. | DSDSDS | Ward makes much of Walther’s abstention from sex with Hildegund in the wilderness. Instead of treating her as spoils of war, he shows respect for her noble status and her potential to become a wife and mother of heirs. Such heirs would need to be incontestable, not sullied by the shadow of extramarital sex. Hence, the poet repeatedly uses the word "virgo" to describe Hildegund (for example, at lines 110, 235, 248, and 287). Though the term “chivalry” is anachronistic in this context, Walther’s careful respect for Hildegund as a marriageable woman (and thus, a stabilizer of culture) and his avoidance of the sin of lust make him a prototype for the later “domesticated” heroes of romance. For Ward, the poem represents the efforts of the Carolingian church to craft just such religious and domestic values. MCD

Perhaps Walther's abstinence is also connected with the other associations with Lent? [JJTY] | ||||

| Ecce quater denos sol circumflexerat orbes, | Quater denos: the length of time is perhaps of biblical inspiration.

|

Aeneid 5.131: circumflectere cursus. . . ‘To double round the courses. . .’

|

DSSSDS | Walther and Hildegund wander in the wilderness between the land of the Huns and the territory of Worms for forty days, a period which echoes the wandering of the Jews prior to their entrance into the Promised Land (cf. Exodus, Leviticus, Numbers, Deuteronomy), the number of days and nights that Moses spends on the mountaintop (cf. Exodus 24:18), the period of Christ’s temptation in the desert (cf. Matthew 4:1-11; Mark 1:13-14; Luke 4:1-15), and the length of Lent. The specification of forty days is no accident, but as usual in the poem, the function of such a religious reference is unclear.

It may imply a spiritual significance to Walter’s ordeal, fulfilled in the “justice” meted out by the poem’s peculiar ending. Similarly, if Walter and Hildegund’s journey functions as a kind of Lent, then Walther’s bloody battle might constitute an analogue to Good Friday or other older and more indigenous tales of human sacrifice and rebirth. Indeed, after passing through the carnage and loss of Walther’s single combat, order, friendship, and loyalty are reborn and restored in a kind of resurrection. The time specification may also emphasize that the Waltharius is a tale preliminary to Walter’s illustrious rule, much as the wanderings of Christ or the Israelites in the desert forms a prelude to a well-known, public career. Alternatively, the specification of forty days may simply function as yet another vague and attenuated religious reference in the poem, like the references to fauns (ll. 761-763) or Wieland (ll. 965-966). Though Christianity can be assumed to be a more "living" religion to the Waltharius-poet, the references to Christian belief through the poem are almost as enigmatic as the references to Germanic or Roman practice. Christianity has a similarly ambiguous status in Beowulf, so this might be a common feature of Germanic poetry written relatively soon after the introduction of Christianity. MCD | ||

| Ex quo Pannonica fuerat digressus ab urbe. | SDDSDS | |||||

| Ipso quippe die, numerum qui clauserat istum, | 430 | SDDSDS | ||||

| Venerat ad fluvium iam vespere tum mediante, | Vespere…mediante equiv. to medio vespere

|

Secundum Iohannem 7.14: iam autem die festo mediante. . . ‘Now about the midst of the feast. . .’

|

DDSDDS | |||

| Scilicet ad Rhenum, qua cursus tendit ad urbem | Rhenum: the Rhine River.

|

Aeineid 5.834: cursum contendere iussi. ‘They are bidden to shape their course.’ 12.909: nequiquam avidos extendere cursus/ velle videmur. ‘We seem to strive in vain to press on our eager course.’

|

DSSSDS | |||

| Nomine Wormatiam regali sede nitentem. | Wormatiam: Worms, a city on the Rhine in present-day Germany, here the capital (regali sede) of the Franks, now ruled by Gunther. The route that Waltharius is taking home is a very circuitous one.

|

|

DDSSDS | Worms has existed at least since the time of Julius Caesar. In the fifth century, it became the Burgundian capital, not the Frankish seat, though it remained an important state center when the Franks came to occupy the Rhineland in later centuries. It features in another German epic, the 12th-century Nibelungenlied, when Gunther and Hagan appear again, this time as Burgundians. The Nibelungenlied, though written during the High Middle Ages, would seem to have roots in earlier myth, like the Waltharius, since versions of the story appear in Scandinavian fragments. Indeed, some echoes of the story might be present in the poem itself. Grimm suggested that line 555's "Franci nebulones" might be corrected as "Franci nivilones," though this theory has not met with great favor (see note to line 555). | ||

| Illic pro naulo pisces dedit antea captos | Naulo: “fare” for being ferried across the river.

|

Iona Propheta 1.3: et invenit navem euntem in Tharsis et dedit naulum eius. ‘And he found a ship going to Tharsis: and he paid the fare thereof.’

|

SSSDDS | Parkes suggests that avarice motivates Walther to pay with fish instead of treasure, and that this is contrasted with the generosity of the ferry-man, who gives the fish to Gunther (460). [AE] | ||

| Et mox transpositus graditur properanter anhelus. | 435 | SDDDDS | The heavily dactylic line imitates the swift movement of Walther and Hildegund's journey. MCD |