Difference between revisions of "Waltharius513"

(→Gunther and his companions approach Walther’s camp; Hagen unsuccessfully tries to dissuade the king from attacking it (513–531)) |

|||

| (5 intermediate revisions by 2 users not shown) | |||

| Line 18: | Line 18: | ||

| | | | ||

|{{Meter|scansion=DDSSDS}} | |{{Meter|scansion=DDSSDS}} | ||

| − | | {{Comment|Cornipedem: horse (literally, horn-foot). The hoof was considered to be made of horn similar to the material of an antler. Cato | + | | {{Comment|Cornipedem: horse (literally, "horn-foot"). The hoof was considered to be made of horn similar to the material of an antler. Cato and Virgil both use the word of hooves; interestingly, in was also applied to birds' beaks, warts, and even, according to Pliny, skin over the eye. MCD [It would be good to consider whether the borrowing from Prudentius is solely verbal or whether the original context may shed light upon the new one in the Waltharius. JZ}} |

|- | |- | ||

|[[Exultansque]] [[animis]] [[frustra]] [[sic]] [[fatur1|fatur]] [[ad]] [[auras]]: | |[[Exultansque]] [[animis]] [[frustra]] [[sic]] [[fatur1|fatur]] [[ad]] [[auras]]: | ||

|515 | |515 | ||

| | | | ||

| − | |{{Parallel|'' | + | |{{Parallel|''Aeneid'' 2.386: ''exultans animisque. . .'' ‘Flushed with courage. . .’ 11.491: ''exsultateque animis.'' ‘He exults in courage.’ 11.556: ''ita ad aethera fatur.'' ‘He cries thus to the heavens.’ |

}} | }} | ||

| | | | ||

|{{Meter|scansion=SDSSDS|elision=exultansque animis}} | |{{Meter|scansion=SDSSDS|elision=exultansque animis}} | ||

| − | | | + | |{{Comment|frustra: "in vain." Emphasizes Gunther's vainglory again. MCD}} |

|- | |- | ||

|[[Accelerate]], [[viri1|viri]], [[iam]] [[nunc]] [[capietis]] [[euntem]], | |[[Accelerate]], [[viri1|viri]], [[iam]] [[nunc]] [[capietis]] [[euntem]], | ||

| Line 45: | Line 45: | ||

| | | | ||

|{{Meter|scansion=DDSDDS|elision=H-ELISION: numquam hodie; hodie effugit}} | |{{Meter|scansion=DDSDDS|elision=H-ELISION: numquam hodie; hodie effugit}} | ||

| − | | | + | |{{Comment|Gunther combines Walther with the Huns in his mind to justify his unprovoked attack, imagining Walther the agent of the "theft" of treaty-money from the Franks. An alternative explanation is that he actually blames Walther for stealing from his lord (Attila, in this case) and so feels no compunction about taking back what was his. This implies a level of loyalty to Germanic oaths which he has not previously displayed, however. MCD [In this case the original context in the third Eclogue contrasts amusingly on what happens in the Waltharius and would be worth discussing. JZ]}} |

|- | |- | ||

|[[Inclitus]] [[at]] [[Hagano]] [[contra1|contra]] [[mox]] [[reddidit]] [[ista2|ista]]: | |[[Inclitus]] [[at]] [[Hagano]] [[contra1|contra]] [[mox]] [[reddidit]] [[ista2|ista]]: | ||

| Line 87: | Line 87: | ||

| | | | ||

|{{Meter|scansion=SDDSDS}} | |{{Meter|scansion=SDDSDS}} | ||

| − | | | + | |{{Comment|The Hunnish battle early in the poem, before Walther speaks with Hildegund about escape, places the reader or listener's sympathies firmly with Hagan, since we too have "seen" Walther fight. MCD}} |

|- | |- | ||

|[[Vidi]] [[Pannonias1|Pannonias]] [[acies]], [[cum]] [[bella]] [[cierent]] | |[[Vidi]] [[Pannonias1|Pannonias]] [[acies]], [[cum]] [[bella]] [[cierent]] | ||

| | | | ||

| | | | ||

| − | |{{Parallel|'' | + | |{{Parallel|''Aeneid'' 1.541: ''bella cient.'' ‘They stir up wars.’ Statius, ''Thebaid ''11.487: ''cum bella cieret. . .'' ‘When he made war. . .’ |

}} | }} | ||

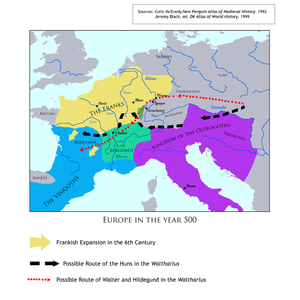

|{{Pictures|[[Image:Europe500.png|center|thumb]]}} | |{{Pictures|[[Image:Europe500.png|center|thumb]]}} | ||

| Line 113: | Line 113: | ||

| | | | ||

|{{Meter|scansion=SDDSDS}} | |{{Meter|scansion=SDDSDS}} | ||

| − | | {{Comment| | + | | {{Comment|"coruscus": see note to l. 453. Once again the poet uses images of light; this time Walther's manliness shines for the whole world. The exact repetition of the adjective "coruscus" from the ferryman's description also calls back to mind the image of the perfect warrior which Gunther has conveniently forgotten in order to convince his men that Walther is "imbellus" (see l. 486). MCD}} |

|- | |- | ||

|[[Hostibus]] [[invisus]], [[sociis1|sociis]] [[mirandus]] [[obibat]]: | |[[Hostibus]] [[invisus]], [[sociis1|sociis]] [[mirandus]] [[obibat]]: | ||

| | | | ||

| | | | ||

| − | |{{Parallel|'' | + | |{{Parallel|''Aeneid'' 6.167:'' lituo pugnas insignis obibat et hasta. '' ‘He braved the fray, glorious for clarion and spear alike.’ |

}} | }} | ||

| | | | ||

| Line 127: | Line 127: | ||

| | | | ||

| | | | ||

| − | |{{Parallel|'' | + | |{{Parallel|''Aeneid'' 6.134-135: ''bis nigra videre/ Tartara. . . '' ‘Twice to see black Tartarus. . .’ |

}} | }} | ||

| | | | ||

|{{Meter|scansion=DSDSDS}} | |{{Meter|scansion=DSDSDS}} | ||

| − | | {{Comment|The Waltharius-poet uses a Virgilian formula here, which may be significant in the effort to place the poem's religious loyalties. Though little is known specifically of continental Germanic paganism, it is generally assumed to bear some similarity to Scandinavian cults, since related tribes colonized the areas during the period of migration following the | + | | {{Comment|The Waltharius-poet uses a Virgilian formula here, which may be significant in the effort to place the poem's religious loyalties. Though little is known specifically of continental Germanic paganism, it is generally assumed to bear some similarity to Scandinavian cults, since related tribes colonized the areas during the period of migration following the fall of Rome. According to what is known of Scandinavian beliefs, a warrior who fell in battle might hope that his soul would fly to Valhalla, a feasting hall in the realm of the gods, where great warriors awaited the final battle, Ragnarok, at the end of the world. Those who passed away from sickness or accident traveled instead to Hel, in an underworld which resembles Roman Tartarus or Christian Hell much more closely than Valhalla. A warrior who perished in battle with Walther, according to such a belief system, was much more fortunate than one who died safe in his bed. Little trace of such an ethos is evident in Hagan's warning, however; he treats death as a fate to be avoided. In this sense, Gunther's later mockery of Hagan's caution perhaps is justified in terms of Germanic religion; that Gunther's world-view is clearly denigrated, however, suggests that the Waltharius-poet wishes to associate all death with the darkness of Hel, stripping it of any (pagan) glory. For a further discussion of Germanic religion, see Rudolf Simek's chapter in ''Early Germanic Literature and Culture,'' ed. Brian Murdoch and Malcolm Read (2004).}} |

|- | |- | ||

|[[O]] [[rex1|rex]] [[et]] [[comites1|comites]], [[experto]] [[credite]], [[quantus]] | |[[O]] [[rex1|rex]] [[et]] [[comites1|comites]], [[experto]] [[credite]], [[quantus]] | ||

| | | | ||

| | | | ||

| − | |{{Parallel|: '' | + | |{{Parallel|: ''Aeneid'' 11.283-284: ''experto credite quantus/ in clipeum adsurgat, quo turbine torqueat hastam. '' ‘Trust one who has experienced it, how huge he looms above his shield, with what whirlwind he hurls his spear.’ |

}} | }} | ||

| | | | ||

|{{Meter|scansion=SDSSDS}} | |{{Meter|scansion=SDSSDS}} | ||

| − | | | + | |{{Comment|"comites": Hagan remembers his fellow warriors and vassals to Gunther. Together, they form [what Tacitus called JZ] a comitatus, a war-band with cohesion and standards of loyalty which also bind Hagan. A betrayal of Gunther for Hagan would also amount to a betrayal of his companions. Hagan's later attempt to abdicate the situation, though perhaps intended to avoid breaking either oath, still leaves them without his protection. Appealing to them, too, is another way to appeal to Gunther, though such an appeal might dangerously undermine his loyalty. MCD}} |

|- | |- | ||

|[[In]] [[clipeum]] [[surgat]], [[quo]] [[turbine]] [[torqueat]] [[hastam]].' | |[[In]] [[clipeum]] [[surgat]], [[quo]] [[turbine]] [[torqueat]] [[hastam]].' | ||

| | | | ||

| | | | ||

| − | |{{Parallel|: '' | + | |{{Parallel|: ''Aeneid'' 11.283-284: ''experto credite quantus/ in clipeum adsurgat, quo turbine torqueat hastam. '' ‘Trust one who has experienced it, how huge he looms above his shield, with what whirlwind he hurls his spear.’ |

}} | }} | ||

| | | | ||

|{{Meter|scansion=DSSDDS}} | |{{Meter|scansion=DSSDDS}} | ||

| − | | {{Comment| | + | | {{Comment|The poet's use of parallel structure emphasizes Walther's great skill as a balanced warrior: he has no weaknesses. MCD}} |

|- | |- | ||

|[[sed1|Sed]] [[dum]] [[Guntharius]] [[male]] [[sana]] [[mente]] [[gravatus]] | |[[sed1|Sed]] [[dum]] [[Guntharius]] [[male]] [[sana]] [[mente]] [[gravatus]] | ||

|530 | |530 | ||

| | | | ||

| − | |{{Parallel|'' | + | |{{Parallel|''Aeneid'' 4.8: ''male sana. . . '' ‘Much distraught. . .’ |

}} | }} | ||

| | | | ||

|{{Meter|scansion=SDDSDS}} | |{{Meter|scansion=SDDSDS}} | ||

| − | | | + | |{{Comment|Gunther is "weighed down with an unhealthy mind." The poet is probably not suggesting that Gunther is insane, but he certainly does behave irrationally and obsessively with regard to Walther and the treasure he carries, sacrificing all his best men in the attempt to defeat him. Avarice itself, in the poet's mind, might be a kind of insanity. This is connected to the Platonic idea that the man ruled by his passions is a slave, devoid of true power, excluded from the "kingship" of rationality, which would probably have been familiar to the Waltharius-poet through Boethius. MCD [A citation is needed, at least to Boethius, to justify the mention of Plato. JZ] |

| + | |||

| + | Perhaps this would be more akin to Stoicism rather than Platonism? [JJTY]}} | ||

|- | |- | ||

|[[Nequaquam]] [[flecti]] [[posset]], [[castris1|castris]] [[propriabant]]. | |[[Nequaquam]] [[flecti]] [[posset]], [[castris1|castris]] [[propriabant]]. | ||

Latest revision as of 15:23, 17 December 2009

Gunther and his companions approach Walther’s camp; Hagen unsuccessfully tries to dissuade the king from attacking it (513–531)

| Ast ubi Guntharius vestigia pulvere vidit, | Georgics 3.171: summo vestigia pulvere signent. ‘Let them print their tracks on the surface of the dust.’ Statius, Thebaid 6.640: raraque non fracto vestigia pulvere pendent. ‘The rare footsteps hover and leave the dust unbroken.’

|

DDSDDS | ||||

| Cornipedem rapidum saevis calcaribus urget, | Prudentius, Psychomachia 253-254.: talia vociferans rapidum calcaribus urget/ cornipedem. ‘Thus exclaiming she spurs on her swift charger and flies wildling along with loose rein.’ Statius, Thebaid 11.452-453.: saevis calcaribus urgent/ immeritos. ‘With savage goads they incite their innocent teams.’

|

DDSSDS | Cornipedem: horse (literally, "horn-foot"). The hoof was considered to be made of horn similar to the material of an antler. Cato and Virgil both use the word of hooves; interestingly, in was also applied to birds' beaks, warts, and even, according to Pliny, skin over the eye. MCD [It would be good to consider whether the borrowing from Prudentius is solely verbal or whether the original context may shed light upon the new one in the Waltharius. JZ | |||

| Exultansque animis frustra sic fatur ad auras: | 515 | Aeneid 2.386: exultans animisque. . . ‘Flushed with courage. . .’ 11.491: exsultateque animis. ‘He exults in courage.’ 11.556: ita ad aethera fatur. ‘He cries thus to the heavens.’

|

SDSSDS Elision: exultansque animis |

frustra: "in vain." Emphasizes Gunther's vainglory again. MCD | ||

| Accelerate, viri, iam nunc capietis euntem, | DDSDDS | |||||

| Numquam hodie effugiet, furata talenta relinquet.' | Furata: passive in sense, though from a deponent.

|

Eclogue 3.49: numquam hodie effugies. ‘This time you won’t get away!’

|

DDSDDS Elision: H-ELISION: numquam hodie; hodie effugit |

Gunther combines Walther with the Huns in his mind to justify his unprovoked attack, imagining Walther the agent of the "theft" of treaty-money from the Franks. An alternative explanation is that he actually blames Walther for stealing from his lord (Attila, in this case) and so feels no compunction about taking back what was his. This implies a level of loyalty to Germanic oaths which he has not previously displayed, however. MCD [In this case the original context in the third Eclogue contrasts amusingly on what happens in the Waltharius and would be worth discussing. JZ] | ||

| Inclitus at Hagano contra mox reddidit ista: | DDSSDS | |||||

| Unum dico tibi, regum fortissime, tantum: | SDSSDS | |||||

| Si totiens tu Waltharium pugnasse videres | 520 | Videres equiv. to vidisses

|

DSDSDS | |||

| Atque nova totiens, quotiens ego, caede furentem, | Aeineid 2.499-500.: vidi ipse furentem/ caede Neoptolemum. ‘I myself saw Neoptolemus, mad with slaughter.’ 8.695: arva nova Neptunia caede rubescunt. Neptune’s fields redden with strange slaughter.’ 10.514-515.: te, Turne, superbum/ caede nova. . . ‘You, Turnus, still flushed with fresh slaughter. . .’

|

DDDDDS | ||||

| Numquam tam facile spoliandum forte putares. | SDDSDS | The Hunnish battle early in the poem, before Walther speaks with Hildegund about escape, places the reader or listener's sympathies firmly with Hagan, since we too have "seen" Walther fight. MCD | ||||

| Vidi Pannonias acies, cum bella cierent | Aeneid 1.541: bella cient. ‘They stir up wars.’ Statius, Thebaid 11.487: cum bella cieret. . . ‘When he made war. . .’

|

SDDSDS | ||||

| Contra Aquilonares sive Australes regiones: | Aquilonares equiv. to Aquilonias

|

DSSSDS Elision: contra Aquilonares; sive Australes |

Since the beginning of the poem is spent establishing that all of western Europe fears the Huns, Hagan's assertion that he is greater than them carries considerable weight. MCD | |||

| Illic Waltharius propria virtute coruscus | 525 | SDDSDS | "coruscus": see note to l. 453. Once again the poet uses images of light; this time Walther's manliness shines for the whole world. The exact repetition of the adjective "coruscus" from the ferryman's description also calls back to mind the image of the perfect warrior which Gunther has conveniently forgotten in order to convince his men that Walther is "imbellus" (see l. 486). MCD | |||

| Hostibus invisus, sociis mirandus obibat: | Aeneid 6.167: lituo pugnas insignis obibat et hasta. ‘He braved the fray, glorious for clarion and spear alike.’

|

DSDSDS | ||||

| Quisquis ei congressus erat, mox Tartara vidit. | Aeneid 6.134-135: bis nigra videre/ Tartara. . . ‘Twice to see black Tartarus. . .’

|

DSDSDS | The Waltharius-poet uses a Virgilian formula here, which may be significant in the effort to place the poem's religious loyalties. Though little is known specifically of continental Germanic paganism, it is generally assumed to bear some similarity to Scandinavian cults, since related tribes colonized the areas during the period of migration following the fall of Rome. According to what is known of Scandinavian beliefs, a warrior who fell in battle might hope that his soul would fly to Valhalla, a feasting hall in the realm of the gods, where great warriors awaited the final battle, Ragnarok, at the end of the world. Those who passed away from sickness or accident traveled instead to Hel, in an underworld which resembles Roman Tartarus or Christian Hell much more closely than Valhalla. A warrior who perished in battle with Walther, according to such a belief system, was much more fortunate than one who died safe in his bed. Little trace of such an ethos is evident in Hagan's warning, however; he treats death as a fate to be avoided. In this sense, Gunther's later mockery of Hagan's caution perhaps is justified in terms of Germanic religion; that Gunther's world-view is clearly denigrated, however, suggests that the Waltharius-poet wishes to associate all death with the darkness of Hel, stripping it of any (pagan) glory. For a further discussion of Germanic religion, see Rudolf Simek's chapter in Early Germanic Literature and Culture, ed. Brian Murdoch and Malcolm Read (2004). | |||

| O rex et comites, experto credite, quantus | : Aeneid 11.283-284: experto credite quantus/ in clipeum adsurgat, quo turbine torqueat hastam. ‘Trust one who has experienced it, how huge he looms above his shield, with what whirlwind he hurls his spear.’

|

SDSSDS | "comites": Hagan remembers his fellow warriors and vassals to Gunther. Together, they form [what Tacitus called JZ] a comitatus, a war-band with cohesion and standards of loyalty which also bind Hagan. A betrayal of Gunther for Hagan would also amount to a betrayal of his companions. Hagan's later attempt to abdicate the situation, though perhaps intended to avoid breaking either oath, still leaves them without his protection. Appealing to them, too, is another way to appeal to Gunther, though such an appeal might dangerously undermine his loyalty. MCD | |||

| In clipeum surgat, quo turbine torqueat hastam.' | : Aeneid 11.283-284: experto credite quantus/ in clipeum adsurgat, quo turbine torqueat hastam. ‘Trust one who has experienced it, how huge he looms above his shield, with what whirlwind he hurls his spear.’

|

DSSDDS | The poet's use of parallel structure emphasizes Walther's great skill as a balanced warrior: he has no weaknesses. MCD | |||

| Sed dum Guntharius male sana mente gravatus | 530 | Aeneid 4.8: male sana. . . ‘Much distraught. . .’

|

SDDSDS | Gunther is "weighed down with an unhealthy mind." The poet is probably not suggesting that Gunther is insane, but he certainly does behave irrationally and obsessively with regard to Walther and the treasure he carries, sacrificing all his best men in the attempt to defeat him. Avarice itself, in the poet's mind, might be a kind of insanity. This is connected to the Platonic idea that the man ruled by his passions is a slave, devoid of true power, excluded from the "kingship" of rationality, which would probably have been familiar to the Waltharius-poet through Boethius. MCD [A citation is needed, at least to Boethius, to justify the mention of Plato. JZ]

Perhaps this would be more akin to Stoicism rather than Platonism? [JJTY] | ||

| Nequaquam flecti posset, castris propriabant. | Propiabant equiv. to appropinquabant

|

SSSSDS |