Difference between revisions of "Waltharius142"

(→Walther rejects Attila’s offer of a bride (142–169)) |

Ana Enriquez (talk | contribs) (→Walther rejects Attila’s offer of a bride (142–169)) |

||

| (One intermediate revision by one other user not shown) | |||

| Line 55: | Line 55: | ||

| | | | ||

|{{Meter|scansion=SDSDDS}} | |{{Meter|scansion=SDSDDS}} | ||

| − | |{{Comment|"Causa" is used here in a sense which arose in Later Latin, | + | |{{Comment|"Causa" is used here in a sense, meaning "thing," which arose in Later Latin and which survives to this day in the Romance languages, as in French "chose" and Italian "cosa." Du Cange’s Glossarium mediae et infimae latinitatis cites this meaning of "causa" in the laws of the Lombards and in the laws of Charlemagne. [AE]}} |

|- | |- | ||

|[[Intuitu]] [[fertis]], [[numquam]] [[meruisse]] [[valerem]]. | |[[Intuitu]] [[fertis]], [[numquam]] [[meruisse]] [[valerem]]. | ||

| Line 148: | Line 148: | ||

| | | | ||

|{{Meter|scansion=SDSDDS}} | |{{Meter|scansion=SDSDDS}} | ||

| − | |{{Comment|This | + | |{{Comment|This line manifests with particular acuteness one aspect of the Germanic warrior ethos, namely, love for the lord above all else. However, since the audience knows Walther is promised to Hildegund, and we will soon see the two plot together against Attila, it has the ring of irony. [AE] |

Hagan will later honor his love for his lord above his personal loyalties, and one interpretation of the poem's end is that he is punished for his desertion of Walther. Walther's defection here is thus preferable to abandoning Hildegund. Alternatively, Walther too might be punished for the breach of loyalty to his lord with the loss of his hand, just as Hagan is punished for his breach of loyalty to a friend with the loss of his eye. [MCD]}} | Hagan will later honor his love for his lord above his personal loyalties, and one interpretation of the poem's end is that he is punished for his desertion of Walther. Walther's defection here is thus preferable to abandoning Hildegund. Alternatively, Walther too might be punished for the breach of loyalty to his lord with the loss of his hand, just as Hagan is punished for his breach of loyalty to a friend with the loss of his eye. [MCD]}} | ||

|- | |- | ||

| Line 158: | Line 158: | ||

| | | | ||

|{{Meter|scansion=DDSDDS}} | |{{Meter|scansion=DDSDDS}} | ||

| − | |{{Comment|The language here echoes Aeneid 4.16, which reads, “ne cui me vinclo vellem sociare iugali….” Dido | + | |{{Comment|The language here echoes Aeneid 4.16, which reads, “ne cui me vinclo vellem sociare iugali….” Dido uses these words when talking to her sister Anna about how she might be susceptible to Aeneas, if only she had not decided to avoid “nuptial chains.” Dido goes on to fall for Aeneas, just as Walther, despite what he says, will go on to marry Hildegund. The other parallel, which will return later in the poem, is between Attila and Dido, who are the ones the hero leaves behind. [AE]}} |

|- | |- | ||

|[[me1|Me]] [[vinclo]] [[permitte]] [[me1|me]]am [[iam]] [[ducere]] [[vitam]]. | |[[me1|Me]] [[vinclo]] [[permitte]] [[me1|me]]am [[iam]] [[ducere]] [[vitam]]. | ||

| Line 164: | Line 164: | ||

| | | | ||

|{{Parallel|''Liber Malachim IV ''5.2: ''Quae erat in obsequio uxoris Naaman.'' ‘She waited upon Naaman’s wife.’ ''Aeneid 4.16:'' ''ne cui me vinclo vellem sociare iugali. . .'' ‘To ally myself with none in bond of wedlock. . .’ | |{{Parallel|''Liber Malachim IV ''5.2: ''Quae erat in obsequio uxoris Naaman.'' ‘She waited upon Naaman’s wife.’ ''Aeneid 4.16:'' ''ne cui me vinclo vellem sociare iugali. . .'' ‘To ally myself with none in bond of wedlock. . .’ | ||

| − | <br />'' | + | <br />''Aeneid'' 3.315: ''vitamque extrema per omnia duco''. ‘I drag on my life through all extremes.’ |

}} | }} | ||

| | | | ||

| Line 173: | Line 173: | ||

| | | | ||

| | | | ||

| − | |{{Parallel|''Secundum Marcum'' 13.35: ''sero an media nocte''. . . ‘At evening or at midnight. . .’'' | + | |{{Parallel|''Secundum Marcum'' 13.35: ''sero an media nocte''. . . ‘At evening or at midnight. . .’'' Aeneid'' 8.407: ''medio noctis.'' . . ‘In the middle of the night. . .’ |

}} | }} | ||

| | | | ||

|{{Meter|scansion=SDSDDS|elision=sero aut}} | |{{Meter|scansion=SDSDDS|elision=sero aut}} | ||

| − | |{{Comment|The phrase "sero aut medio noctis" also appears in the Gospel of Mark, when Christ tells the parable of the faithful servant, who keeps watch because he does not know at what hour his lord will return. This parable is a metaphor for the return of Christ. In using this language, the Waltharius poet reminds his readers that Walther is a Christian, just as he does in lines [[Waltharius215|225]], when Walther blesses the goblet, and in [[Waltharius1130|1161]], when Walther prays to his Creator. [AE]}} | + | |{{Comment|The phrase "sero aut medio noctis" also appears in the Gospel of Mark 13.35, when Christ tells the parable of the faithful servant, who keeps watch because he does not know at what hour his lord will return. This parable is a metaphor for the return of Christ. In using this language, the Waltharius poet reminds his readers that Walther is a Christian, just as he does in lines [[Waltharius215|225]], when Walther blesses the goblet, and in [[Waltharius1130|1161]], when Walther prays to his Creator. [AE]}} |

|- | |- | ||

|[[Ad]] [[quaecumque]] [[iubes]], [[securus]] [[et]] [[ibo]] [[paratus]]. | |[[Ad]] [[quaecumque]] [[iubes]], [[securus]] [[et]] [[ibo]] [[paratus]]. | ||

| Line 207: | Line 207: | ||

|{{Commentary|''Testor'': here construed like ''precor'' with a purpose clause, joining an oath to an earnest request. | |{{Commentary|''Testor'': here construed like ''precor'' with a purpose clause, joining an oath to an earnest request. | ||

}} | }} | ||

| − | |{{Parallel|'' | + | |{{Parallel|''Aeneid'' 3.599-600.: ''per sidera testor,/ per superos atque hoc caeli spirabile lumen,/ tollite me. '' ‘By the stars I beseech you, by the gods above and this lightsome air we breathe, take me.’ 1.555: ''pater optime. . . '' ‘Noble father. . .’ |

}} | }} | ||

| | | | ||

|{{Meter|scansion=SDSDDS}} | |{{Meter|scansion=SDSDDS}} | ||

| − | |{{Comment|It is strange that Walther refers to Attila as "pater" here. However, Attila may mean "little father" in Old Turkic, which was possibly the language of the Huns. | + | |{{Comment|It is strange that Walther refers to Attila as "pater" here. However, Attila may mean "little father" in Old Turkic, which was possibly the language of the Huns. This etymology might explain this strange remark. For a full discussion of Attila's name, see Otto Maenchen-Helfen, The World of the Huns: Studies in their history and culture (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1973), chapter 4. The phrase "pater optime" also appears in Aeneid 1.555, where it seems to refer to Jupiter, and in 3.710, where Aeneas uses it in reference to Anchises. [AE]}} |

|- | |- | ||

|[[Atque]] [[per]] [[invictam]] [[nunc]] [[gentem]] [[Pannoniarum]] | |[[Atque]] [[per]] [[invictam]] [[nunc]] [[gentem]] [[Pannoniarum]] | ||

Latest revision as of 20:10, 15 December 2009

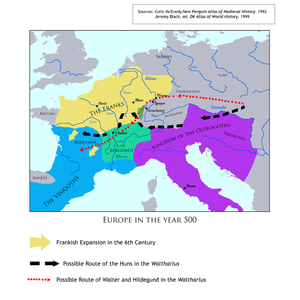

Walther rejects Attila’s offer of a bride (142–169)

| Waltharius venit, cui princeps talia pandit, | Ipse: Waltharius, who begins speaking in line 146. (Attila’s repetition of his wife’s speech is elided.)

|

Aeineid 3.179: remque ordine pando. ‘I reveal all in order.’ 6.723: suscipit Anchises atque ordine singula pandit. ‘Anchises replies, and reveals each truth in order.’

|

DSSSDS | |||

| Uxorem suadens sibi ducere; sed tamen ipse | SSDDDS | |||||

| Iam tum praemeditans, quod post compleverat actis, | Quod: obj. of praemeditans

|

Secundum Lucam 21.14: non praemeditari quemadmodum respondeatis. ‘Do not meditate before how you should answer.’

|

SDSSDS | |||

| His instiganti suggestibus obvius infit: | 145 | Suggestibus equiv. to consiliis

|

SSSDDS | |||

| Vestra quidem pietas est, quod modici famulatus | Modici famulatus: genitive of description with causa, meaning “of little importance” or “that has provided some small service.”

|

DDSDDS | ||||

| Causam conspicitis. sed quod mea segnia mentis | Causam: here, as often in the Waltharius, this word is practically the equivalent of res – well on its way to becoming French chose, Italian/Spanish cosa, “thing.” Mea segnia: i.e., Waltharius’s delay in making a decision regarding marriage.

|

SDSDDS | "Causa" is used here in a sense, meaning "thing," which arose in Later Latin and which survives to this day in the Romance languages, as in French "chose" and Italian "cosa." Du Cange’s Glossarium mediae et infimae latinitatis cites this meaning of "causa" in the laws of the Lombards and in the laws of Charlemagne. [AE] | |||

| Intuitu fertis, numquam meruisse valerem. | Mentis intuitu fertis equiv. to attenditis

|

DSSDDS | ||||

| Sed precor, ut servi capiatis verba fidelis: | DSDSDS | |||||

| Si nuptam accipiam domini praecepta secundum, | 150 | Secundum: the post-positive preposition

|

SDDSDS Elision: nuptam accipiam |

|||

| Vinciar in primis curis et amore puellae | DSSDDS | |||||

| Atque a servitio regis plerumque retardor: | Retardor: Like cogor and moratur below, with a future sense.

|

SDSSDS Elision: atque a |

||||

| Aedificare domos cultumque intendere ruris | DDSSDS Elision: cultumque intendere |

|||||

| Cogor, et hoc oculis senioris adesse moratur | DDDDDS | |||||

| Et solitam regno Hunorum impendere curam. | 155 | Georgics 2.433: et dubitant homines serere atque impendere curam? ‘And can men be slow to plant and bestow care?’

|

DSSSDS Elision: Hunorum impendere Hiatus: regno Hunorum |

|||

| Namque voluptatem quisquis gustaverit, exin | DSSSDS | |||||

| Intolerabilius consuevit ferre labores. | Intolerabilius: here active in sense, “with less tolerance.”

|

DDSSDS | ||||

| Nil tam dulce mihi, quam semper inesse fideli | SDSDDS | This line manifests with particular acuteness one aspect of the Germanic warrior ethos, namely, love for the lord above all else. However, since the audience knows Walther is promised to Hildegund, and we will soon see the two plot together against Attila, it has the ring of irony. [AE]

Hagan will later honor his love for his lord above his personal loyalties, and one interpretation of the poem's end is that he is punished for his desertion of Walther. Walther's defection here is thus preferable to abandoning Hildegund. Alternatively, Walther too might be punished for the breach of loyalty to his lord with the loss of his hand, just as Hagan is punished for his breach of loyalty to a friend with the loss of his eye. [MCD] | ||||

| Obsequio domini; quare precor absque iugali | Liber Malachim IV 5.2: Quae erat in obsequio uxoris Naaman. ‘She waited upon Naaman’s wife.’ Aeneid 4.16: ne cui me vinclo vellem sociare iugali. . . ‘To ally myself with none in bond of wedlock. . .’

|

DDSDDS | The language here echoes Aeneid 4.16, which reads, “ne cui me vinclo vellem sociare iugali….” Dido uses these words when talking to her sister Anna about how she might be susceptible to Aeneas, if only she had not decided to avoid “nuptial chains.” Dido goes on to fall for Aeneas, just as Walther, despite what he says, will go on to marry Hildegund. The other parallel, which will return later in the poem, is between Attila and Dido, who are the ones the hero leaves behind. [AE] | |||

| Me vinclo permitte meam iam ducere vitam. | 160 | Liber Malachim IV 5.2: Quae erat in obsequio uxoris Naaman. ‘She waited upon Naaman’s wife.’ Aeneid 4.16: ne cui me vinclo vellem sociare iugali. . . ‘To ally myself with none in bond of wedlock. . .’

|

SSDSDS | |||

| Si sero aut medio noctis mihi tempore mandas, | Secundum Marcum 13.35: sero an media nocte. . . ‘At evening or at midnight. . .’ Aeneid 8.407: medio noctis. . . ‘In the middle of the night. . .’

|

SDSDDS Elision: sero aut |

The phrase "sero aut medio noctis" also appears in the Gospel of Mark 13.35, when Christ tells the parable of the faithful servant, who keeps watch because he does not know at what hour his lord will return. This parable is a metaphor for the return of Christ. In using this language, the Waltharius poet reminds his readers that Walther is a Christian, just as he does in lines 225, when Walther blesses the goblet, and in 1161, when Walther prays to his Creator. [AE] | |||

| Ad quaecumque iubes, securus et ibo paratus. | SDSDDS | |||||

| In bellis nullae persuadent cedere curae | SSSSDS | |||||

| Nec nati aut coniunx retrahentque fugamque movebunt. | SSDDDS Elision: nati aut |

|||||

| Testor per propriam temet, pater optime, vitam | 165 | Testor: here construed like precor with a purpose clause, joining an oath to an earnest request.

|

Aeneid 3.599-600.: per sidera testor,/ per superos atque hoc caeli spirabile lumen,/ tollite me. ‘By the stars I beseech you, by the gods above and this lightsome air we breathe, take me.’ 1.555: pater optime. . . ‘Noble father. . .’

|

SDSDDS | It is strange that Walther refers to Attila as "pater" here. However, Attila may mean "little father" in Old Turkic, which was possibly the language of the Huns. This etymology might explain this strange remark. For a full discussion of Attila's name, see Otto Maenchen-Helfen, The World of the Huns: Studies in their history and culture (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1973), chapter 4. The phrase "pater optime" also appears in Aeneid 1.555, where it seems to refer to Jupiter, and in 3.710, where Aeneas uses it in reference to Anchises. [AE] | |

| Atque per invictam nunc gentem Pannoniarum | Nunc: an ironic touch? (Cf. line 144)

|

DSSSDS | ||||

| Ut non ulterius me cogas sumere taedas.' | SDSSDS | |||||

| His precibus victus suasus rex deserit omnes, | DSSSDS | |||||

| Sperans Waltharium fugiendo recedere numquam. | SDDDDS |