Difference between revisions of "Waltharius75"

(→The Aquitainians under Alphere surrender to Attila, giving Walther as a hostage (75–92)) |

|||

| Line 44: | Line 44: | ||

| | | | ||

|{{Meter|scansion=DDSSDS}} | |{{Meter|scansion=DDSSDS}} | ||

| − | |{{Comment|Youth is equated several times in the poem with the blooming of a flower, most notably when Hagan accuses Walter of having committed an unpardonable offense by killing his nephew, whom he describes as a blooming flower | + | |{{Comment|Youth is equated several times in the poem with the blooming of a flower, most notably when Hagan accuses Walter of having committed an unpardonable offense by killing his nephew, whom he describes as a blooming flower at lines 1273-4. |

'''Here as in the other passage, the phrase is used as a means of eliciting pathos, in this case a feeling of pity for Walter who has to go into exile at such a young age. [JJTY]'' | '''Here as in the other passage, the phrase is used as a means of eliciting pathos, in this case a feeling of pity for Walter who has to go into exile at such a young age. [JJTY]'' | ||

Latest revision as of 05:20, 16 December 2009

The Aquitainians under Alphere surrender to Attila, giving Walther as a hostage (75–92)

| Postquam complevit pactum statuitque tributum, | 75 | SSSDDS | ||||

| Attila in occiduas promoverat agmina partes. | DDSDDS Elision: Attila in |

|||||

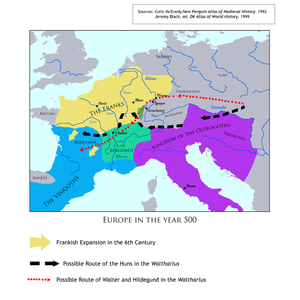

| Namque Aquitanorum tunc Alphere regna tenebat, | Aquitanorum: The region of Aquitaine is in present-day south-western France. Alphere: Apparently legendary.

|

Aeneid 7.735: . . .Teleboum Capreas cum regna teneret. ‘. . .When he reigned over Teleboan Capreae.’

|

DSSDDS Elision: namque Aquitanorum |

|||

| Quem sobolem sexus narrant habuisse virilis, | DSSDDS | |||||

| Nomine Waltharium, primaevo flore nitentem. | Waltharium: The protagonist of the epic; apparently legendary.

|

Aeineid 7.162: primaevo flore iuventus. . . ‘Youths in their early bloom. . .’ Statius, Silvae 5.1.183: vidi omni pridem te flore nitentem. ‘I have seen thee in the full splendour of they fame.’

|

DDSSDS | Youth is equated several times in the poem with the blooming of a flower, most notably when Hagan accuses Walter of having committed an unpardonable offense by killing his nephew, whom he describes as a blooming flower at lines 1273-4.

'Here as in the other passage, the phrase is used as a means of eliciting pathos, in this case a feeling of pity for Walter who has to go into exile at such a young age. [JJTY] "nitentem": one of many instances in which the Waltharius-poet uses words describing Walther or Hildegund as "glittering" or "shining." Combining the image of light with the image of the flower is particularly striking. MCD | ||

| Nam iusiurandum Heriricus et Alphere reges | 80 | SSDDDS Hiatus: iusiurandum Heriricus |

||||

| Inter se dederant, pueros quod consociarent, | Pueros quod consociarent: “that they would unite their children,” i.e., Waltharius and Hiltgunt, in marriage. Quod + subjunctive here replaces, as often, the Classical accusative + infinitive construction.

|

SDDSDS | ||||

| Cum primum tempus nubendi venerit illis. | SSSSDS | The heavily spondaic nature of the line (5 spondees) could reflect a sense in which the two children cannot grow up soon enough--in which the time for their marriage seems like it will never come. | ||||

| Hic ubi cognovit gentes has esse domatas, | DSSSDS | |||||

| Coeperat ingenti cordis trepidare pavore, | Aeneid 6.491: ingenti trepidare metu. ‘They trembled with a mighty fear.’ 2.685: nos pavidi trepidare metu. . . ‘We, trembling with alarm. . .’ 7.458: olli somnum ingens rumpit pavor. ‘A monstrous terror broke his sleep.’ Lucan, De Bello Civili 5.530: nullo trepidare tumultu. . . ‘To thrill with no alarm. . .’

|

DSSDDS | ||||

| Nec iam spes fuerat saevis defendier armis. | 85 | Aeneid 8.492-493.: ille inter caedem Rutulorum elapsus in agros/ confugere et Turni defendier hospitis armis. ‘Amid the carnage, he flees for refuge to Rutulian soil and find shelter among the weapons of Turnus his friend.’ 12.890: saevis certandum est comminus armis. ‘We must contend hand to hand with savage weapons.’

|

SDSSDS | |||

| 'Quid cessemus', ait, 'si bella movere nequimus? | Aeneid 6.820: nova bella moventis. . . ‘Stirring up revolt. . .’ 12.332-333.: sanguineus Mavors clipeo increpat atque furentis/ bella movens immittit equos. ‘Blood-stained Mavors, stirred to fury, thunders with his shield and, rousing war, gives rein to his frenzied steeds.’

|

SDSDDS | "movere": The Aquitanians seem to lack both the means and the will after the surrenders of the Burgundians and the Franks even to 'stir up' a war, let alone to 'wage' a war ("bellum gerere"). | |||

| Exemplum nobis Burgundia, Francia donant. | SSSDDS | |||||

| Non incusamur, si talibus aequiperamur. | SSSDDS | |||||

| Legatos mitto foedusque ferire iubebo | Aeineid 10.154: foedusque ferit. ‘He strikes a treaty.’

|

SSSDDS | ||||

| Obsidis inque vicem dilectum porrigo natum | 90 | Obsidis in vicem equiv. to pro obside

|

DDSSDS | |||

| Et iam nunc Hunis censum persolvo futurum.' | SSSSDS | The spondaic nature of the line - SSSDS - could reflect Alphere's sadness at having to hand over his son to Attila. | ||||

| Sed quid plus remorer? dictum compleverat actis. | Aeineid 2.102: quidve moror? ‘Why do I delay?’ Liber Numerorum 11.23: iam nunc videbis utrum meus sermo opere conpleatur. ‘Thou shalt presently se whether my word shall come to pass or no.’

|

SDSSDS | The poet uses a common narratological tool to speed up the course of the story by avoiding needless repetition. |