Waltharius287

Walther hosts a luxurious banquet for Attila’s court; eventually all his intoxicated guests fall asleep (287–323)

| Virgo memor praecepta viri complevit. et ecce | DSDSDS | 288-323 The opening scene of the book of Esther is an important parallel to this feast scene. Here King Xerxes arranges a great feast in Susa “that he might show the riches of the glory of his kingdom, and the greatness, and boasting of his power” (1.4), but his overdrinking leads him to shame himself when his beautiful wife Vashti refuses his drunken command that she parade in front of the court. This refusal leads him to depose his queen and hunt for another, who will be Esther. SB. | ||||

| Praefinita dies epularum venit, et ipse | Aeneid 1.637-642; 1.697-708; 8.175-183. Prudentius, Apotheosis 712-713. Liber Hester chapter 1.

|

SDDSDS | ||||

| Waltharius magnis instruxit sumptibus escas. | Aeneid 1.637-642; 1.697-708; 8.175-183. Prudentius, Apotheosis 712-713. Liber Hester chapter 1.

|

DSSSDS | ||||

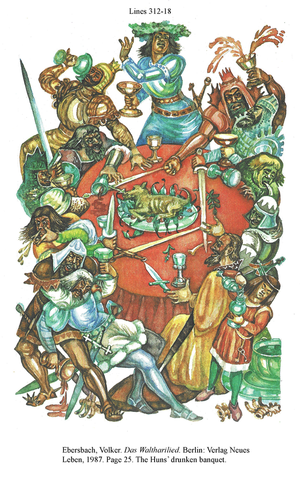

| Luxuria in media residebat denique mensa, | 290 | Luxuria: personified

|

Aeneid 1.637-642; 1.697-708; 8.175-183. Prudentius, Apotheosis 712-713. Liber Hester chapter 1.

|

DDDSDS Elision: luxuria in |

Luxuria in media residebat denique mensa “and then Luxury settled in the middle of the table”; contrast with 315 where another vice, Drunkenness (Ebrietas), rules the hall. We progress from one vice to another. Both terms are associated in early Christian sources with sexual impropriety, and specifically sodomy. Ambrose of Milan, De Abraham 1.3.14: “Sodoma enim luxuria atque lasciuia est” (C. Schenkl, ed., CSEL 32.1, Prague1897, 512). Jerome, Commentary on Ezekiel 5.16.552-3: “Sodoma uocatur et Samaria, quarum altera gentilem uitam luxuriam que significat, altera haereticorum decipulas” (F. Glorie, ed. CCSL 75, Turnhout 1964, 202). John Cassian (c. 360 – 435), De institutis coenobiorum et de octo principalium uitiorum remediis libri XII 5.6: “Sodomitis causa subuersionis atque luxuriae non uini crapula, sed saturitas extitit panis” (M. Petschenig, ed., CSEL 17, Vienna 1888, 86). See M. D. Jordan, “Homosexuality, luxuria, and textual abuse,” Constructing medieval sexuality, ed. K. Lochrie, P. McCracken, and J. A. Schultz (Minneapolis 1997), pp. 24-39. SB.

This personification of Luxuria in connection with Drunkenness is also redolent of Prudentius, Psychomachia 378-388. It is interesting that Luxuria is there described as "coming from the East" ("378-9: Venerat occiduis mundi de finibus hostis / Luxuria), just as in the Waltharius a scene is painted of eastern decadence. [JJTY] [An early installment of what Edward Said would call "orientalism" (JZ)? | |

| Ingrediturque aulam velis rex undique septam. | Septam equiv. to saeptam, here “hung with” tapestries (velis), although a certain double-entendre in reference to the trap that is about to “enclose” Attila and his court may be intended.

|

Aeneid 1.637-642; 1.697-708; 8.175-183. Prudentius, Apotheosis 712-713. Liber Hester chapter 1.

|

DSSSDS Elision: ingrediturque aulam |

|||

| Heros magnanimus solito quem more salutans | Aeneid 1.637-642; 1.697-708; 8.175-183. Prudentius, Apotheosis 712-713. Liber Hester chapter 1.

|

SDDSDS | ||||

| Duxerat ad solium, quod bissus compsit et ostrum. | Bissus: “fine linen”

|

Aeneid 1.637-642; 1.697-708; 8.175-183. Prudentius, Apotheosis 712-713. Liber Hester chapter 1.

|

DDSSDS | bissus comspit et ostrum Compare the description of the king’s hall in Esther 1.6: “And there were hung up on every side sky coloured, and green, and violet hangings, fastened with cords of silk, and of purple, which were put into rings of ivory, and were held up with marble pillars. The beds also were of gold and silver, placed in order upon a floor paved with porphyry and white marble: which was embellished with painting of wonderful variety” (“et pendebant ex omni parte tentoria aerii coloris et carpasini et hyacinthini sustentata funibus byssinis atque purpureis qui eburneis circulis inserti erant et columnis marmoreis fulciebantur lectuli quoque aurei et argentei super pavimentum zmaragdino et pario stratum lapide dispositi erant quod mira varietate pictura decorabat”). Luxurious, foreign elements seem to dominate. SB. | ||

| Consedit laterique duces hinc indeque binos | Aeneid 1.637-642; 1.697-708; 8.175-183. Prudentius, Apotheosis 712-713. Liber Hester chapter 1.

|

SDDSDS | ||||

| Assedisse iubet; reliquos locat ipse minister. | 295 | Aeneid 1.637-642; 1.697-708; 8.175-183. Prudentius, Apotheosis 712-713. Liber Hester chapter 1.

|

SDDDDS | |||

| Centenos simul accubitus iniere sodales, | Centenos equiv. to centum Accubitus: the word implies the ancient practice of reclining on couches while eating, but the poet probably simply means “seat.”

|

Aeneid 1.637-642; 1.697-708; 8.175-183. Prudentius, Apotheosis 712-713. Liber Hester chapter 1.

|

SDDDDS | accubitus presumably these are not meant to be reclining seats as used by the Romans, but perhaps benches. On the other hand, in keeping with the depiction of the Hunnish court as exotic and luxurious, it is possible that the original valence is intended. SB | ||

| Diversasque dapes libans conviva resudat. | Resudat: The parallel in Prudentius suggests that this “sweating out” is a sign of over-indulgence, not pleasure. Singular for plural.

|

Aeneid 1.637-642; 1.697-708; 8.175-183. Prudentius, Apotheosis 712-713. Liber Hester chapter 1.

|

SDSSDS | resudat possibly from the spiciness of the food. But the parallels in Prudentius remind us that this whole passage serves as a warning against drunkenness and luxury, with Esther as the source of the moral: King Xerxes humiliates himself because he has had too much to drink. exquisitum fervebat migma per aurum Compare the silverware in Esther 1.7: “And they that were invited, drank in golden cups, and the meats were brought in divers vessels one after another. Wine also in abundance and of the best was presented, as was worthy of a king's magnificence.” (“bibebant autem qui invitati erant aureis poculis et aliis atque aliis vasis cibi inferebantur vinum quoque ut magnificentia regia dignum erat abundans et praecipuum ponebatur”). SB. | ||

| His et sublatis aliae referuntur edendae, | Aeneid 1.637-642; 1.697-708; 8.175-183. Prudentius, Apotheosis 712-713. Liber Hester chapter 1.

|

SSDDDS | ||||

| Atque exquisitum fervebat migma per aurum | Migma: “mixture,” probably some sort of warm drink, e.g. mulled wine (not mead, as this was drunk cold).

|

Aeneid 1.637-642; 1.697-708; 8.175-183. Prudentius, Apotheosis 712-713. Liber Hester chapter 1.

|

SSSSDS Elision: atque exquisitum |

exquisitum fervebat migma per aurum Compare the silverware in Esther 1.7: “And they that were invited, drank in golden cups, and the meats were brought in divers vessels one after another. Wine also in abundance and of the best was presented, as was worthy of a king's magnificence.” (“bibebant autem qui invitati erant aureis poculis et aliis atque aliis vasis cibi inferebantur vinum quoque ut magnificentia regia dignum erat abundans et praecipuum ponebatur”). SB.[migma has occasioned a bit of perplexity, being construed most often as mixed wine but sometimes as food: see Novum Glossarium, ed. Blatt, col. 472. JZ] | ||

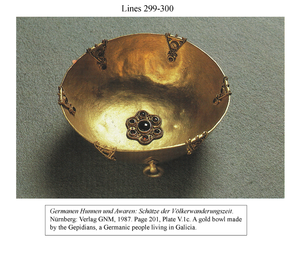

| Aurea bissina tantum stant gausape vasa -- | 300 | Bissina…gausape: “linen tablecloth.” The noun is not feminine in Classical authors.

|

Aeneid 1.637-642; 1.697-708; 8.175-183. Prudentius, Apotheosis 712-713. Liber Hester chapter 1.

|

DSSSDS | ||

| Et pigmentatus crateres Bachus adornat. | Pigmentatus…Bachus: usually interpreted as “spiced wine;” German wine of the period was sour and had to be sweetened or flavored. But a miniature ecphrasic description of the appearance of the painted crateres (“mixing bowls,” here perhaps “cups”) also seems possible, given the emphasis on the material and visual (aurea, bissina, adornat, species) in this context.

|

Aeneid 1.637-642; 1.697-708; 8.175-183. Prudentius, Apotheosis 712-713. Liber Hester chapter 1.

|

SSSSDS | pigmentatus the idea seems to be that the contents were spicy [or aromatic: JZ], not that the vessel was painted. Either interpretation, however, would contribute to the louche imagery of this type-scene. SB | ||

| Illicit ad haustum species dulcedoque potus. | Aeneid 1.637-642; 1.697-708; 8.175-183. Prudentius, Apotheosis 712-713. Liber Hester chapter 1.

|

DSDSDS | for a vivid picture of a Germanic drinking bout, as opposed to a classical or biblical bout, see Beowulf lines 491-498. It is perhaps best not to assume that this drinking bout is exclusively Germanic, Classical, or Biblical. SB. | |||

| Waltharius cunctos ad vinum hortatur et escam. | Aeneid 1.637-642; 1.697-708; 8.175-183. Prudentius, Apotheosis 712-713. Liber Hester chapter 1.

|

DSSSDS Elision: vinum hortatur |

||||

| Postquam epulis depulsa fames sublataque mensa, | Sublata mensa: once again it is unclear whether this is merely figurative language for “at the end of the meal,” picking up Virgil’s mensae remotae, or whether the poet envisions the tables being carried out. Althof emphasizes that the use of the singular does not establish that the guests necessarily feasted at one common table.

|

Aeneid 1.637-642; 1.697-708; 8.175-183. Prudentius, Apotheosis 712-713. Liber Hester chapter 1.

|

DSDSDS Elision: postquam epulis |

|||

| Heros iam dictus dominum laetanter adorsus | 305 | Iam dictus: “the aforementioned,” i.e., Waltharius, a metrical crutch.

|

Aeneid 1.637-642; 1.697-708; 8.175-183. Prudentius, Apotheosis 712-713. Liber Hester chapter 1.

|

SSDSDS | ||

| Inquit: 'in hoc, rogito, clarescat gratia vestra, | Aeneid 1.637-642; 1.697-708; 8.175-183. Prudentius, Apotheosis 712-713. Liber Hester chapter 1.

|

DDSSDS | ||||

| Ut vos inprimis, reliquos tunc laetificetis.' | Aeneid 1.637-642; 1.697-708; 8.175-183. Prudentius, Apotheosis 712-713. Liber Hester chapter 1.

|

SSDSDS | ||||

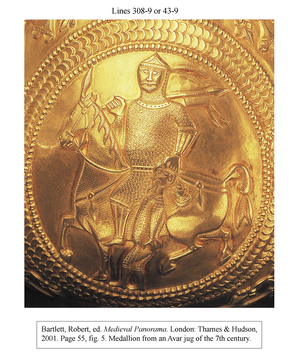

| Et simul in verbo nappam dedit arte peractam | Nappam equiv. to poculum, cf. German Napf.

|

Aeneid 1.637-642; 1.697-708; 8.175-183. Prudentius, Apotheosis 712-713. Liber Hester chapter 1.

|

DSSDDS | Cf. Esther 1.6-7. SB | ||

| Ordine sculpturae referentem gesta priorum, | Aeneid 1.637-642; 1.697-708; 8.175-183. Prudentius, Apotheosis 712-713. Liber Hester chapter 1.

|

DSDSDS | ||||

| Quam rex accipiens haustu vacuaverat uno, | 310 | Aeneid 1.637-642; 1.697-708; 8.175-183. Prudentius, Apotheosis 712-713. Liber Hester chapter 1.

|

SDSDDS | |||

| Confestimque iubet reliquos imitarier omnes. | Aeneid 1.637-642; 1.697-708; 8.175-183. Prudentius, Apotheosis 712-713. Liber Hester chapter 1.

|

SDDDDS | ||||

| Ocius accurrunt pincernae moxque recurrunt, | Pincernae: “cup-bearers,” among the Germans usually noble youths.

|

Aeneid 1.637-642; 1.697-708; 8.175-183. Prudentius, Apotheosis 712-713. Liber Hester chapter 1.

|

DSSSDS | |||

| Pocula plena dabant et inania suscipiebant. | Aeneid 1.637-642; 1.697-708; 8.175-183. Prudentius, Apotheosis 712-713. Liber Hester chapter 1.

|

DDDDDS | Cf. 228, where Walter hands Hildegund an empty cup after drinking. It is worth noting that in Esther 1.8 the king does not, in contradistinction to Walter’s own drinking bout, compel the unwilling to drink (Esther 1.8: nec erat qui nolentes cogeret ad bibendum). SB | |||

| Hospitis ac regis certant hortatibus omnes. | Hospitis: i.e., Waltharius, the host of the banquet.

|

Aeneid 1.637-642; 1.697-708; 8.175-183. Prudentius, Apotheosis 712-713. Liber Hester chapter 1.

|

DSSSDS | |||

| Ebrietas fervens tota dominatur in aula, | 315 | Aeneid 1.637-642; 1.697-708; 8.175-183. Prudentius, Apotheosis 712-713. Liber Hester chapter 1.

|

DSSDDS | Ebrietas contrast with line 290. Where luxuria formerly reigned, now ebrietas holds sway. The parallels with the story in the book of Esther are striking, for it is in the context of heavy drinking (cum rex esset hilarior et post nimiam potionem) that the king orders his wife Vashti to parade in front of the whole court to show off her beauty, a request that she fatefully refuses. The term is used in a Carolingian capitulum that bemoans the practice of sodomy in monastic communities (A. Boretius, ed., MGH Capitularia regum Francorum 1, Capitulare Missorum Generale (802), c. 17). SB. | ||

| Balbutit madido facundia fusa palato, | Aeneid 1.637-642; 1.697-708; 8.175-183. Prudentius, Apotheosis 712-713. Liber Hester chapter 1.

|

SDSDDS | ||||

| Heroas validos plantis titubare videres. | Aeneid 1.637-642; 1.697-708; 8.175-183. Prudentius, Apotheosis 712-713. Liber Hester chapter 1.

|

SDSDDS | ||||

| Taliter in seram produxit bachica noctem | Produxit bachica…munera: “prolonged the drinking”

|

Aeneid 1.637-642; 1.697-708; 8.175-183. Prudentius, Apotheosis 712-713. Liber Hester chapter 1.

|

DSSSDS | |||

| Munera Waltharius retrahitque redire volentes, | Aeneid 1.637-642; 1.697-708; 8.175-183. Prudentius, Apotheosis 712-713. Liber Hester chapter 1.

|

DDDDDS | ||||

| Donec vi potus pressi somnoque gravati | 320 | Aeneid 1.637-642; 1.697-708; 8.175-183. Prudentius, Apotheosis 712-713. Liber Hester chapter 1.

|

SSSSDS | |||

| Passim porticibus sternuntur humotenus omnes. | Aeneid 1.637-642; 1.697-708; 8.175-183. Prudentius, Apotheosis 712-713. Liber Hester chapter 1.

|

SDSDDS | humotenus “groundwards” a word that the Waltharius poet likes, and which is either a neologism or exceedingly rare (it is absent from the Thesaurus Linguae Latinae and from several other Latin dictionaries), though its meaning is clear enough. SB [The word could be construed equally well as being two: humo + tenus, a preposition that is usually placed postpositively. Thus humotenus is comparable to mecum or tecum, which could be written separately--as honoris causa is. JZ] | |||

| Et licet ignicremis vellet dare moenia flammis, | Licet…remansit equiv. to etiamsi voluisset dare…nullus remansisset Ignicremis equiv. to igne cremantibus – a rare word, but not coined by this poet.

|

Aeneid 1.637-642; 1.697-708; 8.175-183. Prudentius, Apotheosis 712-713. Liber Hester chapter 1.

|

DDSDDS | Cf. the prediction of the destruction of Heorot in Beowulf, trans. Seamus Heaney, p. 7, lines 81-64: "The hall towered, / its gables wide and high and awaiting / a barbarous burning. That doom abided, / but in time it would come" SB | ||

| Nullus, qui causam potuisset scire, remansit. | Causam equiv. to rem (cf. line 325 below and note on line 147).

|

SSDSDS |